etters have featured throughout the novel. Some, like the rose-pink showers at the beginning, have been written from mistaken motives. Others, like Lady Blandish's to Sir Austin about Lucy, have been poorly understood. Still others, like Lucy's to Richard in the Rhineland, have not even been read. Two letters, Richard's to Ripton and Bella, have reached people to whom they were not addressed. Now one, received belatedly, has had exactly the opposite effect to that intended: Bella's letter has worked not to prevent but to trigger catastrophe.

etters have featured throughout the novel. Some, like the rose-pink showers at the beginning, have been written from mistaken motives. Others, like Lady Blandish's to Sir Austin about Lucy, have been poorly understood. Still others, like Lucy's to Richard in the Rhineland, have not even been read. Two letters, Richard's to Ripton and Bella, have reached people to whom they were not addressed. Now one, received belatedly, has had exactly the opposite effect to that intended: Bella's letter has worked not to prevent but to trigger catastrophe.

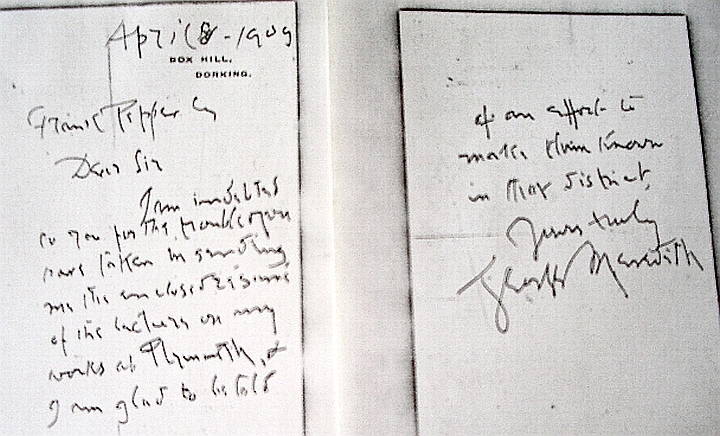

A rather poignant letter written by Meredith in old age. With thanks to the Dorking Museum, Surrey. [Click on the thumbnail for a larger image].

However, the role of letters in this painfully disturbing "History of Father and Son" is not yet complete. In itself, the last letter in the novel is direct and to the point. Its recipient can be expected to understand it perfectly, and to respond exactly as wished. The questions it poses are for the real reader rather than the fictional one. Apparently intent on destroying "the conventional form of the novel," as Virginia Woolf once put it (533), Meredith ends the whole narrative inconclusively with a long letter from Lady Blandish. It is an emotional and questioning "lady's letter" like her earlier one to Sir Austin (201); but by now she has entirely lost faith in his wisdom. She is appealing instead to his nephew, the younger, more dependable Austin Wentworth, reporting that Richard has been badly wounded, and that when Sir Austin barred Lucy from tending him so that she could devote herself instead to the infant — his precious grandchild — she developed that old malady, brain fever, and died. Now, Lady Blandish continues, Richard himself is recovering, but has received the dreadful news about Lucy as a "death-blow to his heart." The so-called "Hope of Raynham," she believes, will now "never be what he promised" (492).

This seems a truly wretched letter. And indeed, the events themselves are bleak enough. All nature seems implicated in this tragedy. Richard's weakness with Bella was the result of natural instinct. As Mrs Berry had said of her own philandering husband: �what [young men] goes and does they ain’t quite answerable for: they feels, I dare say, pushed from behind’ (455-6). Moreover, Richard has failed partly, it seems, through having inherited his father’s inflexibility. Now, worse still perhaps, Lady Blandish fears that Sir Austin is so impervious to life's lessons that he might try to inflict his damaging "System" on the next generation — that is, on Richard's now motherless boy: "All I pray is that this young child may be saved from him" (491), she says. Here, as in the sonnets of "Modern Love" still to come, Meredith's whole world-view seems coloured by his despair over human folly (see Lund 382).

Yet, as in that well-known sequence, this is not the whole story. Richard’s experience in the forest, when he thrills to the ‘Spirit of Life’ (465), must be taken into account. So must Mrs Berry’s simple belief in Providence: �I think it al’ays the plan in a dielemmer to pray God and walk forward’ (441). And so too, must the very existence of the child, always something positive in Meredith. Finally, there is the purpose of this concluding letter. Even the most private letters are different from diaries or journals. Their intentions for their fictional reader need to be considered. Here, Lady Blandish is writing to Austin.first and foremost because Richard has asked for him. This in itself is a promising sign. She herself wants Austin to come, expecting that he will make her more charitable towards Sir Austin. The younger Austin can be counted on to support them all. In this way, Lady Blandish’s letter is not merely a "dazzling solution to the technical problem" of how to report such sad events sympathetically in an otherwise impersonally, indeed, often cynically told narrative (Mendelson xxiv). It provides the last scene of an action on which the curtain has yet to fall. Structurally as well as thematically, this invitation leaves open possibilities for change and growth.

Meredith employs various quirky and/or innovative devices in his narratives. Amongst them are metafictional narrators like Dame Gossip in The Amazing Marriage, "with her artful pother to rouse excitement at stages of a narrative" (593); interior monologues, such as Victor Radnor's as he struggles to grasp his elusive 'Idea' in One of Our Conquerors; and of course aphorisms, which are a special feature both of this early novel and of his first popular success, Diana of the Crossways. But he uses more traditional devices as well, including diary entries and letters, and it is in these that he first shows his heightened consciousness of "the real and the fictional reader," a consciousness that "is a living principle in work after work of his, growing as the whole matrix of his aesthetic grows" (Wilt 4). Specifically, the letters in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel" reveal how concerned he was with our difficulty in communicating with each other, and how strongly he felt about the need for such communication. Advances in communications technology notwithstanding, these would become still more pressing problems not only in his own later novels, but in the literature of the succeeding age in general.

Related Material

- Letters in George Meredith’s The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (Part I: Arson and Amor)

- Letters in George Meredith’s The Ordeal of Richard Feverel (Part II: In the Toils of the "System")

- Topics to investigate

- "The Frame Text in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel."

Works Cited

Brontë, Anne. The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. Ed. Stevie Davies. London: Penguin Classics, 1996.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. London: Penguin Popular Classics, 1994.

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d'Urbervilles: A Pure Woman. New York: Scribner's, 1893. Available online here.

Lund, Michael. "Space and Spiritual Crisis in Meredith's 'Modern Love.'" Victorian Poetry. Vol. 16. No. 4 (Winter 1978): 376-82.

Mendelson, Edward. Introduction. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel: A History of Father and Son. By George Meredith. London: Penguin Classics, 1998. xi-xxviii.

Meredith, George. The Amazing Marriage. New York: Scribner's, 1895. Available online here.

_____. Diana of the Crossways. New York: Scribner's, 1905. Available online here.

_____. Evan Harrington. New York: Scribner's, 1900. Available online here.

_____. Letters. Ed. C.L. Cline, 3 Vols. Oxford: Clarendon, 1970.

_____. One of Our Conquerors. New York: Scribner's, 1899. Available online here.

_____. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel: A History of Father and Son. Ed. Edward Mendelson. London: Penguin Classics, 1998. See note at the end of Part I.

Stoker, Bram. Dracula. Ed. Maurice Hindle. London: Penguin Classics, 2004.

Wilt, Judith. The Readable People of George Meredith. Princeton: Princteon University Press, 1975.

Woolf, Virginia. “The Novels of George Meredith.” Rpt. in George Meredith: The Egoist: An Annotated Text, Backgrounds, Criticisms. Ed. Robert M. Adams. New York: Norton, 1979. 531-9.

Last modified 7 July 2010