I was one day admiring one of the falls of the Clyde; and ruminating upon what descriptive term could be most fitly applied to it, I came to the conclusion that the epithet "majestic" was the most appropriate. While I was still contemplating the scene, a gentleman and a lady came up, neither of whose faces bore much of the stamp of superior intelligence, and the first words the gentleman uttered were "It is very majestic." I was pleased to find such a confirmation of my opinion, and I complimented the spectator upon the choice of his epithet, saying that he had used the best word that could have been selected from our language "Yes, sir," replied the gentleman," I say it is very majestic: it is sublime, It is beautiful, it is grand, it is picturesque." — "Ay (added the lady), it is the prettiest thing I ever saw." I own that I was not a little disconcerted. — Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridge's Shakespearean Criticism, ed. T. M. Raysor, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (London and New York, 1960), II, 37.

3.I. Ruskin's Theory of the Sublime

USKIN used his theory of the sublime, like the theory of beauty which it complements, to solve the problem of the role of emotion in beauty and art. Ruskin's theoretical formulations of the sublime changed during the writing of Modern Painters, and the course of this change is an index of his attempts to find place for the disordering, subjective elements of emotion in his aesthetic system. Since he at first believed that his notion of beauty could embrace what earlier authors had relegated to the sublime, he thought his aesthetic would not require a theory of sublimity. In the first volume of Modern Painters when Ruskin is outlining his theory of art, he pauses to inform the reader why he has neither taken any notice of the sublime in art nor once used the term:

The fact is, that sublimity is not a specific term, — not a term descriptive of the effect of a particular class of ideas. Anything which elevates the mind is sublime, and elevation of mind is produced by the contemplation of greatness of ally kind.... Sublimity is, therefore, only another word for the effect of greatness upon the feelings; — greatness, whether of matter, space, power, virtue, or beauty.... The sublime is not distinct from what is beautiful, nor from other sources of pleasure in art, but is only a particular mode and manifestation of them. (3.128,130)

When Ruskin firmly denies that beauty and sublimity are separate and distinct aesthetic categories, he departs from Addison, Burke, and Wordsworth, the writers who contributed most to his conception of the sublime. He is prompted to disagree with his predecessors, because, in keeping with his characteristic desire to derive all aesthetics from the unity of the human spirit, Ruskin wishes to emphasize that the human mind receives undivided pleasures from nature and art. He was not, however, long able to maintain this unified conception of aesthetic effects, and, already, by the next volume of Modern Painters , he had reverted, in the manner of earlier theorists, to contrasting beauty and sublimity. The manuscripts of the second and third volumes of Modern Painters contain sections on the sublime, which the editors of the Library Edition have included in appendices for the appropriate volumes. Although Ruskin did not use these sections in which he partially formulated his own theory of the sublime, his remarks throughout the second and later volumes make it clear that the omitted sections represent Ruskin's true position, and that they reveal the changes which had taken place in his conception of sublimity. In one of the most interesting of the sections originally intended for the second volume, Ruskin contradicted his first view that sublimity can merely be a mode of the beautiful:

It will readily, I believe, be admitted that many things are sublime in the highest degree, which are not in the highest degree beautiful, and vice versa; i.e. that the two ideas are distinct, and one is not merely a particular form or state of the other. (4.369)

This statement shows that Ruskin now accepts that beauty and sublimity are distinct forms of aesthetic pleasure; and, as we shall see, his uses of the terms "sublime" and "sublimity" make it clear that he also tended to oppose the sublime to the beautiful.

Ruskin reversed his initial position, returning to older conceptions of sublimity, because, like the eighteenth-century theorists who first used the sublime as a separate category, he had discovered the need for a means of complementing a classicistic theory of calm, ordered beauty. Ruskin began Modern Painters with a partially developed philosophy of beauty which, he thought, would encompass previous notions of both beauty and sublimity; but, in fact, once his ideas of the beautiful had taken form in the second volume of Modern Painters, it appeared that they excluded too much; and so, repeating the procedure of the eighteenth-century originators of the sublime, Ruskin used a second aesthetic category to include the pleasures of nature and art which he himself enjoyed so much but which he could not consider beautiful — the pleasures of strong, even violent emotion, of asymmetry, of the awesome, the terrible, and the vast.

That Ruskin tried and failed to create a unified, encompassing system of aesthetics indicates the transitional nature of his position in the history of aesthetics and art theory. It was paradoxical and yet inevitable that after English critics had first opposed beauty to sublimity they would have next attempted to reconcile the two categories once the sublime had become the dominant concern of aesthetic speculation. The sublime allowed the critics to discuss sources of aesthetic pleasure — particularly violent emotional reactions — which they excluded from neoclassical conceptions of beauty. When, however, the sublime dominated mid- and late eighteenth-century English aesthetics, notions associated with the sublime affected the older, neoclassical theories of beauty. Under the influence of the sublime, writers on aesthetics came to believe that beauty was [184/185] a matter of emotion and not reason, and that, moreover, it should be described in terms of an emotional reaction and not in terms of qualities residing in the perceived object. After changes in conceptions of the beautiful had removed the basic opposition between sublime emotions and the qualities of beauty, the way was open for theorists to bring ideas of beauty and sublimity closer together. If one looks at the history of the sublime, one can see how it served to introduce new sources of beauty into modern Western thought. In the sixteenth century few considered mountains very attractive; in the eighteenth century many were captivated by their sublimity, if not their beauty; and in the twentieth century most people would regard the usual sources of eighteenth-century sublimity — mountains, seas, and skies — as sources of beauty. A parallel change in theories of sublimity has also taken place in this century, and the usual approach is to merge the sublime with the beautiful, or to deny that it exists as an aesthetic category. Ruskin, in 1843, wanted to unite these two forms of aesthetic experience, but his conservative notions of the beautiful prevented his effecting a satisfactory synthesis.

Since Ruskin's ideas of the sublime draw heavily upon previous writers, it will be useful and appropriate to examine briefly the history of the sublime before considering the details and changes of Ruskin's own theories. He was familiar from childhood with the writings of Addison and Johnson, both of whom discuss important aspects of theories of the sublime; and before beginning Modern Painters Ruskin had become well acquainted with Burke, whose treatise was one of the most influential and original aesthetic statements of the eighteenth century. Perhaps of equal importance to Ruskin's notions of sublimity was his early and continued reading of poets, such as Young and Wordsworth, who presented images of the natural sublime about which the theorists and critics had written. The discussion of the sublime was perhaps the single most important concern of eighteenth-century British aesthetics; but despite the frequency, or possibly because of the frequency, with which the term appears in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century critical and creative literature, it had no one meaning that would have satisfied its many uses. According to Samuel Holt Monk, whose study of the eighteenth-century sublime is a landmark in modern recognition of the importance of this aesthetic idea, "No single definition of the term would serve in any single decade for all writers . . .; but the word naturally expressed high admiration, and usually implied a strong emotional effect, which, in the latter years of the century, frequently turned on terror" (233). The origins and functions of the sublime explain why it meant so many things to so many critics. Critics used the sublime as a category in which they could place aesthetic pleasures excluded from neoclassical ideas of beauty. Furthermore, the sublime itself had arisen in sources as different as a new notion of moral psychology, the rediscovery of a Greek rhetorician, and a theological controversy over whether or not the earth was a ruin which recorded man's fall from grace.

In her Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite (1959), Marjorie Hope Nicolson has shown how the theological controversy over the earth's present form, which engaged or influenced most of the important theologians, scientists, and men of letters of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, created a great interest in the natural sublime. When Thomas Burnet, Master of the Charterhouse and chaplain to King William, published his Sacred Theory of the Earth in 1681, he had hoped to add to science and theology by citing an alternate Biblical tradition which held that the earth, until the Deluge, had been a smooth, featureless, perfectly proportionate sphere, but that afterward it was marred by mountains and scarred by the deep, uneven beds of rivers and seas. According to Miss Nicolson, Burnet was convinced that the terrestrial globe of the 1680s was not identical with the original world. Its gross irregularities and lack of symmetry offended his sense of proportion; "there appearing nothing of Order, or any regular Design in its Parts, it seems reasonable to believe that it was not the Work of Nature, according to her first Intention, or according to the first Model that was drawn in Measure and Proportion by the Line and by the Plummet, but a secondary Work, and the best that could be made of broken Materials.... [Both earth and moon are] in my Judgment the Image or Picture of a great Ruin, and have the true aspect of a World lying in its Rubbish"(196-197).

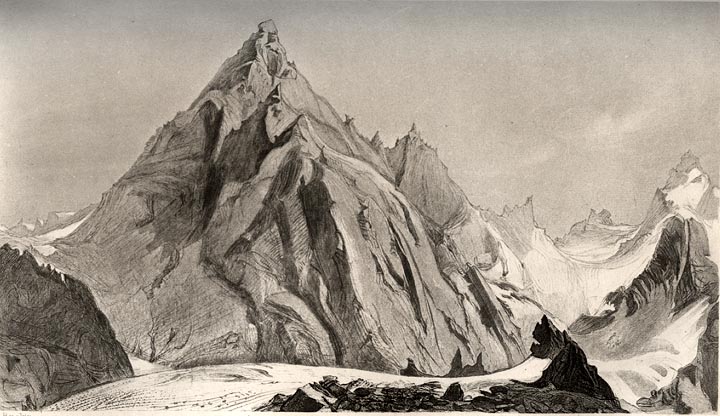

An example of the Mountain Sublime from Ruskin's drawings:

The Aiguille

Blaitière,

which

is reproduced facing Works, 6.230.

[Not in print edition;

click on thumnbail

for larger image.]

But, as Miss Nicolson has also shown, Burnet was a paradoxical man in a paradoxical age; for although he was prompted to condemn the mountains and seas of the earth on theological grounds, he was simultaneously attracted to them; and in his attraction we have the beginnings of landscape feeling, and of the love of the powerful and asymmetrical, which so moved Ruskin and his predecessors. In a physico-theology that became the expanding, changing work of a lifetime appear the interests that were characteristic of later writers on the sublime: 188/189] Burnet was "rapt" and "ravished" by the vast, the grand, the majestic (215). Before vastness he experienced the awe and wonder he had associated with God. But he could not understand his own emotions. He knew that his response was not to "Beauty." On every possible occasion, he sharply differentiated between response to Beauty and the new emotions inspired by the grandeur of Nature. Vast and irregular mountains were not beautiful, but, except for the vast and irregular night skies, nothing had ever moved Burnet to such awe or so led his mind to thoughts of God and infinity as did the mountains and the sea: "The greatest Objects of Nature are, methinks, the most pleasing to behold; and next to the Great Concave of the Heavens, and those boundless Regions where the Stars inhabit, there is nothing that I look upon with more Pleasure than the wide Sea and the Mountains of the Earth" (214).

Burnet's interest in the overpowering aspects of nature, his concern with the effects of this awesomeness on man, his relation of this awe to religion, and his opposition of this new rapturous emotion to beauty prepared for a new aesthetic. Addison, Steele, Joseph Warton, Young, Wordsworth, and Coleridge, among many others, read and were moved by Burnet's Sacred Theory. In addition, the controversy that his ideas provoked, when theologians resisted the idea that the earth was a ruin, made his notions a matter of common currency among theologians, scientists, and writers, and turned their attentions to the attractiveness of the external world of mountains and seas.

Although there is no evidence that he read Burnet, we may point out in passing that Ruskin himself was not only concerned with the kind of approach to nature that Burnet had made important but also that in the fourth volume of Modern Painters he frequently dwells on the possibility that the earth is a ruin of a once greater and more perfect beauty. At one point in the fourth volume, which purports to be about mountain beauty but which often verges on a physico-theology, Ruskin asks: "From what first created forms were the mountains brought into their present condition? . . . The present conformation of the earth appears dictated, as has been shown in the preceding chapters, by supreme wisdom and kindness. And yet its former state must have been different from what it is now; as its present one from that which it must assume hereafter. Is this, therefore, the earth's prime into which we are born: or is it, with all its beauty, only the wreck of Paradise?" (6.177). In addition to an interest, similar to Burnet's, in a now vanished state of the earth, Ruskin also parallels his predecessor when he creates "appalling" images of nature in ruins.6

Burnet's emphasis on external nature and the pleasantly awed reaction it produces in the observer prepared the way for the reception of Longinus's fifth-century fragmentary treatise on the rhetorical sublime. Although there were at least five editions or translations of Longinus during the seventeenth century, critics appear to have paid little attention to the work until Burnet's writings demanded a new vocabulary which Longinus was able to provide. When Boileau translated Longinus's Peri Hupsous in 1674, he made available a critical terminology which could be applied to the new interest in external nature which was soon to come into prominence. But although the grand or high style of rhetoric had from its origin the purpose of arousing emotion, critics had to effect a transference of terms from the Longinian rhetorical sublime to the aesthetic natural sublime of the theorists. As Samuel Holt Monk has pointed out: "To write on the sublime style is to write on rhetoric; to write on sublimity is to write on aesthetic. The sublime style is a means to an end; sublimity is an end in itself" (12). Although the terminology of the sublime was rapidly translated from rhetoric to aesthetics, many influential writers on sublimity, including Addison and Shaftesbury, did not employ the word "sublime," and instead used such partial synonyms as "the great," "the unlimited," "the majestic," and "the stupendous."

To John Dennis, Pope's Sir Tremendous Longinus, must go the credit of initiating a sophisticated introduction of Longinian terminology into an aesthetic of the sublime. Dennis's The Grounds of Criticism in Poetry (1704) continued trends which Burnet had begun, but also added new important emphases. He continued the separation of the beautiful and the sublime, and he also maintained the association of the sublime with religious awe. Dennis's most important contribution to the theory of the sublime was that he was the first critic to pay much attention to the effect the sublime object had upon the beholder (45). According to Nicolson, Dennis's originality lay in the fact that he based his conceptions of sublimity "not upon rhetorical theories but upon his own experience and upon attitudes native to the English, almost unknown to the French" (281). Perhaps most important, Dennis was also the first writer to introduce terror into considerations of the sublime.

Although Dennis was perhaps the most original theorist of the sublime in the first half of the eighteenth century, Joseph Addison had far more influence upon his contemporaries. Since Ruskin knew Addison's writings from childhood, it will be doubly useful to examine the passage in Spectator 412 (1719) in which Addison defines his notion of greatness, lists the usual sources of natural sublimity, and explains the psychological mechanism of the aesthetic reaction to sublimity:

By greatness I do not only mean the bulk of any single object but the largeness of a whole view considered as one entire piece. Such are the prospects of an open champaign country, a vast uncultivated desert, of huge heaps of mountains, high rocks and precipices, or a wide expanse of waters, where we are not struck with the novelty or beauty of the sight but with that rude kind of magnificence which [192/193] appears in many of these stupendous works of nature. Our imagination loves to be filled with an object, or to grasp at anything that is too big for its capacity. We are flung into a pleasing astonishment at such unbounded views, and feel a delightful stillness and amazement in the soul at the apprehension of them.

Addison here makes several points that continued to be important in later writings on the sublime. First, he states that in some way the sublime requires a unified magnificence. Second, he cites the usual mountains, deserts, and seas as the most sublime parts of external nature. And, lastly, he analyzes the sublime reaction or effect in terms of a pleasure caused by attempting to fill the mind by "too big" an object. Johnson, Gerard, and Burke, among others, provide similar though often more detailed examinations of the sublime effect. Dr. Johnson, for example, remarked in his "Life of Cowley" that the sublime was not within reach of the metaphysical poets, "for they never attempted that comprehension and expanse of thought which at once fills the whole mind, and of which the first effect is sudden astonishment, and the second rational admiration" (Lives of the English Poets, Everyman edition, I, 12). Neither Johnson nor Addison (who described feelings of "pleasing astonishment") believed, like Dennis, that sublimity created feelings of terror and horror in the observer. Most writers on the sublime before Burke agreed that the pleasant feelings of awe, delight, and admiration were the result of contemplating mountain ranges, vast seas, and the other usual examples of natural sublimity.

Edmund Burke, whose Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful was published in 1757, believed, however, that "terror is in all cases whatsoever . . . the ruling principle of the sublime" (58); and, in keeping with his conception of a violently emotional sublime, his idea of astonishment, the effect which almost all theorists mentioned, was more violent than that of his predecessors: "The passion caused by the great and sublime in nature . . . is Astonishment; and astonishment is that state of the soul, in which all its motions are suspended, with some degree of horror. In this case the mind is so entirely filled with its object, that it cannot entertain any other" (57; J. T. Boulton's introduction, which carefully relates Burke's ideas to those of his predecessors, is especially useful, because it enables one to perceive how much of the mainstream of eighteenth-century aesthetics and criticism Ruskin had learned about by reading Burke.). Since Ruskin, who knew and admired Burke's treatise, made it his point of departure for his own discussion of the sublime in the first volume of Modern Painters , it will be useful to look briefly at the most important points in Burke's aesthetic.

In addition to the emphasis which he places on terror, Burke is important because he explained the opposition of beauty and sublimity by a physiological theory. He made the opposition of pleasure and pain the source of the two aesthetic categories, deriving beauty from pleasure and sublimity from pain. According to Burke, the pleasure of beauty has a relaxing effect on the fibers of the body, whereas sublimity, in [194/195] contrast, tightens these fibers. Thus, by using the authority of his ingenious theory, he could oppose the beautiful and sublime: "The ideas of the sublime and the beautiful stand on foundations so different, that it is hard, I had almost said impossible, to think of reconciling them in the same subject, without considerably lessening the effect of the one or the other upon the passions" (113-14). Burke's use of this physiological theory of beauty and sublimity makes him the first English writer to offer a purely aesthetic explanation of these effects; that is, Burke was the first to explain beauty and sublimity purely in terms of the process of perception and its effect upon the perceiver.

The writings of Addison, Burke, and Johnson, and others with whom Ruskin was familiar, contained two themes particularly important to his own conceptions of the sublime. The first was that the sublime should be discussed in terms of its effects upon the perceiver. This concern with the person who enjoys sublimity marked an important change in the course of English aesthetics, since the reactions of the perceiver became, for the first time, more important than the qualities of the pleasing object; and indeed, this shift of critical interest is the history in outline of English aesthetics during the preromantic period. Classical, Renaissance, and eighteenth-century aestheticians who believed that beauty was derived from order defined the beautiful in terms of the qualities of the beautiful object. Thus, the proportions of the Venus di Milo and the proper mixture of unity and variety which it incorporates were, for these critics, the sources of its beauty. On the other hand, those eighteenth-century writers, such as Hume, who derived beauty from utility, and Alison, who derived it from association, suggest that aesthetics should consider the role of the perceiver. But Hume and Alison, and Reynolds, who derives beauty from custom, are not concerned with an aesthetic reaction. Rather they wish to discover what it is that makes certain qualities in a beautiful object pleasing. Thus, according to Hume, men adjudge certain human or equine proportions to be beautiful because these particular proportions are the most efficient for the well-being or usefulness of man and horse. On the other hand, Alison believes that the observer finds certain proportions beautiful merely because he has become accustomed to them and because he has associated pleasant thoughts with them. Although these critics no longer placed complete emphasis on the formal qualities of the pleasing object, they did not examine very deeply the process by which these qualities are perceived as beautiful. Dennis, Burke, and other formulators of the theory of the sublime, who were primarily concerned with the effect of the sublime object upon the observer, therefore, introduced important new interests into English aesthetics; for theories of sublimity, not theories of beauty, applied the psychological speculations of Hobbes, Locke, and Hume himself to aesthetics. When the focus of aesthetic considerations

Alexander Gerard, in 1759, attempted both to describe sublimity in terms of qualities, the method usually reserved for discussions of the beautiful, and to explain the psychological reaction to the sublime qualities: "Objects are sublime, which possess quantity, or amplitude, and simplicity, in conjunction.... When a large object is presented, the mind expands itself to the extent of that object, and is filled with one grand sensation, which totally possessing it, composes it into a solemn sedateness and strikes it with deep silent wonder and admiration: it finds such a difficulty in spreading itself to the dimensions of its object, as enlivens and invigorates its frame: and having overcome the opposition which this occasions, it sometimes imagines itself present in every part of the scene which it contemplates; and from the sense [196/197] moved from an interest in the qualities of the pleasing object to an interest in the internal emotional reaction caused by the perception of the object, the change was accompanied by an implicit acceptance of subjectivity in aesthetic theory — a subjectivity, which, as we have already seen, Ruskin tried to avoid in his theories of beauty.

Some of the implications which the new emphasis upon internal reactions had for aesthetics appear in Burke's examples of sublimity, among which he included power, obscurity, and privations, such as darkness and silence. Sublime darkness or obscurity are not, like the beautiful curves of a Greek urn or statue, isolable qualities of a particular object. They are rather, qualities which pervade an entire scene, qualities, moreover, which describe the observer's experiential, phenomenological relation to what he observes. Whereas the statue's lines exist independently of the spectator, obscurity, which relates to his manner of perceiving, does not. Many of Burke's examples of sublimity, in fact, cannot be equated with formal qualities of an object, but necessarily characterize that experienced relationship between the observer and the observed.

Turning to the works of Turner and Wordsworth — turning, that is, to the painter and poet whom Ruskin most admired during this early period when he formulated his own ideas about aesthetics — one encounters embodiments of Burke's descriptions of sublimity that make explicit this notion of a subjective, experiential world. Turner's Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour's Mouth (1842), one of the paintings in whose defense Ruskin began Modern Painters , plunges us into the midst of a storm at sea: the whirling vortex of water, sea-mist, and smoke draws us into the scene, making us look not at the storm but through it.

Turning to the works of Turner and Wordsworth — turning, that is, to the painter and poet whom Ruskin most admired during this early period when he formulated his own ideas about aesthetics — one encounters embodiments of Burke's descriptions of sublimity that make explicit this notion of a subjective, experiential world. Turner's Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour's Mouth (1842), one of the paintings in whose defense Ruskin began Modern Painters , plunges us into the midst of a storm at sea: the whirling vortex of water, sea-mist, and smoke draws us into the scene, making us look not at the storm but through it.

Ruskin imitates the Turnerian vortex in his own drawings: The Glacier du Bois.

1843. Reproduced facing page 225, Volume 2,Works. [Not in print edition;

click on picture for larger image.]

The power, magnificence, obscurity, and awe of the Burkean formulation all present themselves as major components of the experience. But, again, the viewer, like the painter before him who immersed himself in the storm on the Ariel, does not see these qualities as qualities of an object or scene but as qualities of subjective experience. Furthermore, as Jack Lindsay has shown, Turner's similar early paintings, such as Snowstorm: Hannibal and his army Crossing the Alps (1812), demonstrate the painter discarding earlier neoclassical schemes of composition in an attempt to fuse the elements of form, chiaroscuro, and color. "In their place he put a dynamic form of spiral, an explosive vortex, a field of force." In other words, in place of the static composition, rational and controlled, that implies a conception of the scene-as-object, Turner created a dynamic composition that involved the spectator in a subjective relation to the storm.

Similarly, certain passages in Wordsworth's Excursion, the poem which furnished the epigraph to Modern Painters , present us with the phenomenological world of sublime experience. Thus, although the poem frequently employs the term "sublime," mentioning, for instance, a "burst/Sublime of instrumental harmony," "unity sublime," and the "sublime ascent" of man's hopes, sublimity appears not so much in the use of the term as in the poet's presentation of sublime experience in the midst of a majestic dynamic natural scene of which the spectator becomes a part (Works, V, 145, 306, and 289) . Wordsworth immerses us in the natural sublime, taking us out of the role of spectator, making us sympathetic participants, in the passage where the Solitary stirs the feelings of the narrator by recalling the ecstatic joys of wandering amid the tumult of mountain cataracts:

How divine,

The liberty, for frail, for mortal, man

To roam at large among unpeopled glens

And mountainous retirements . . .

. . . regions consecrate

To oldest time! and, reckless of the storm

That keeps the raven quiet in her nest,

Be as a presence or a motion — one

Among the many there; and while the mists

Flying, and rainy vapours, call out shapes

And phantoms from the crags and solid earth

As fast as a musician scatters sounds

Out of an instrument; and while the streams

(As at a first creation and in haste

To exercise their untried faculties)

Descending from the region of the clouds,

And starting from the hollows of the earth

More multitudinous every moment, rend

Their way before them — what a joy to roam

An equal among mightiest energies;

And haply sometimes with articulate voice,

Amid the deafening tumult, scarcely heard

By him that utters it, exclaim aloud,

[ 200-201] "Rage on, ye elements! let moon and stars

Their aspects lend, and mingle in their turn

With this commotion (ruinous though it be)

From day to night, from night to day, prolonged!" (Works, V,125)

The Solitary does not gaze, a spectator, upon nature as-object; for unlike Gilpin, he is not in search of the picturesque. Instead, he immerses himself in nature-as process, trying with his roaming descent, with his passionate exclamations, to make himself part of the scene he encounters. Many of Burke's "qualities" present themselves to our notice: "the mists/Flying and rainy vapours" exemplify obscurity, the "deafening tumult" loudness, and the "mightiest energies" magnificence and power. But our point is not that the Solitary notices these qualities in a scene before him, but that he immerses himself in the tumult, joining his energy for a brief moment to mightiest energies, as the power, tumult, and magnificence of nature make their incursions upon his consciousness. So powerfully do they act upon him, so powerfully does he project himself toward and into them, that he enters the scene as participant, as one who experiences the sublime. The Solitary's apostrophe to the raging elements suggests chaotic merging of earth, sky, and water — in short, the Turnerian vortex. But it is not the vortex which here chiefly represents the sublime experience. Using a narrative technique that is analogous to cinematic "panning," Wordsworth first places us high on the crags with the speaker, then brings us downward "from the region of the clouds," and finally plunges us into the tumult below. The visual organization, the Miltonic sonorous verse, and the apostrophe in the manner of Lear (who also would participate in the energies of the universe) all involve us in the sublime experience. It was this kind of poetry and this kind of painting, then, which Burke's theoretical formulations imply; and it was these works, favorites of Ruskin himself, for which he would have to find adequate description in his critical theory.

In addition to the fact that the writers with whom Ruskin was familiar discuss sublimity in terms of its effects, they also characteristically make a clear division between the sublime and the beautiful. As a corollary of this opposition of the two aesthetic categories, beauty is often considered less important than sublimity. When Burke contrasts the sublime and the beautiful, for example, he clearly reveals that he believes beauty to be a weaker, feminine form of aesthetic pleasure:

Sublime objects are vast in their dimensions, beautiful ones comparatively small; beauty should be smooth, and polished; the great, rugged and negligent; beauty should shun the right line, yet deviate from it insensibly; the great in many cases loves the right line, and when it deviates, it often makes a strong deviation; beauty should not be obscure; the great ought to be dark and gloomy; beauty should be light and delicate; the great ought to be solid, and even massive. (124)

In the first volume of Modern Painters, Ruskin agrees neither with Burke's separation of beauty and sublimity into two distinct aesthetic categories, nor with his presentation of beauty as less powerful or less important than sublimity. Ruskin wishes, as part of his defense of painting, to demonstrate that beauty is important to human life, and, consequently, he could not admit the view that beauty was little more than prettiness. Since Ruskin believed that the perception of beauty was a moral and religious act, he could not permit the implicit depreciation of the beautiful which accompanied Burke's opposition of it to the sublime. The need to emphasize the importance of beauty, as well as his own characteristic preference for a unified aesthetic, prompted Ruskin's denial that the sublime was a separate and distinct aesthetic category.

In his attempt to associate beauty and sublimity more closely, Ruskin naturally transferred some of his views about beauty to his conception of the sublime. He believed, for example, that beauty, like sublimity, was a matter of disinterested emotion; and since he wished to emphasize disinterestedness, one of his major points about aesthetics, he allowed the ingenuity, but not the truth, of Burke's idea that the sublime is derived from pain and from the desire for self-preservation:

It is not the fear, observe, but the contemplation of death; not the instinctive shudder and struggle of self-preservation, but the deliberate measurement of the doom, which is really great or sublime in feeling.... There is no sublimity in the agony of terror. (3.129)

This theoretical position marks a change from the attitudes of his youth, for, as the verse of his childhood and adolescence reveals, he had previously accepted the aesthetic of horror and congenial dread. For example, these lines he wrote in his fourteenth year refer to the pleasures of terror: [203/204]

It is a terror, yet 'tis sweet,

Upon some broken brow

To look upon the distant sweep

Of ocean spread below. (2.4)

In contrast to this quatrain's use of natural sublimity, one also encounters Ruskin's interest in the more theatrical sublime — and delicious shudder — of Thomas Warton and the gothic novel. His long poem, "The Broken Chain," written the year before he began Modern Painters , contains the following horrific lines:

The chapel vaults are deadly damp,

Their air is breathless all;

The downy bats they clasp and cramp

Their cold wings to the wall;

The bright-eyed eft, from cranny and cleft,

Doth noiselessly pursue

The twining light of the death-worms white,

In the pools of the earth-dew. (2.153)

When Ruskin came to write the first volume of Modern Painters , however, he found he could accept neither Burke's straightforward emphasis on terror nor his physiological explanations. In addition to the fact that he no longer believed one could enjoy terror, he wished to show that sublimity was an aspect of beauty, and Burke's grounding beauty and sublimity in two opposing physiological reactions effectively contradicted Ruskin's unification of the two. Furthermore, Burke's explanation made both beauty and sublimity dependent upon physical causes, whereas Ruskin believed that aesthetic reactions, which take place in the theoretic, or contemplative, faculty, are primarily mental, not physical, in character.

Despite his reservations, in the first volume of Modern Painters Ruskin accepted many points which Burke and others had made about the sublime. First, Ruskin believed that the sublime is concerned with greatness, and, second, that it is a matter of emotion: "Sublimity is . . . only another word for the effect of greatness upon the feelings"(3.128). In addition, when he mentioned greatness of matter, space, power, and virtue (3.128), he chose the usual sources of the sublime. Finally, he maintained the traditional relation of religion, the idea of the holy, to sublimity.

In the second volume of Modern Painters, which appeared three years after the first, Ruskin accepted even more traditional conceptions of the sublime. Most important, he opposed beauty to sublimity. This opposition most clearly (and most appropriately) appears in the sections on typical beauty in which Ruskin discusses the beauties of order. In the section on the beauty of symmetry, for example, he contrasts this form of the beautiful to the sublimity produced by irregularity and asymmetry: "Where there is no symmetry, the effects of passion and violence are increased, and many very sublime pictures derive their sublimity from want of it, but they lose proportionally in the diviner quality of beauty" (4.127). From this statement it would appear that Ruskin not only contrasts beauty and sublimity but that he also allows that passion, violence, and asymmetry create pleasing effects. His acceptance of asymmetry apparently widens his initial definition of the sublime. The chapter on the typical beauty of infinity, on the other hand, contains another opposition between beauty and sublimity which is more in line with Ruskin's first idea that sublimity is merely the effect of greatness upon the feelings. Although writers from Burnet to [204/205] Burke and after had made the infinite one of the chief sources of sublimity, Ruskin concentrated on rather tame features of the infinite, such as its incorporation in variety and in curved lines. At the close of his chapter, however, he mentions a form of the infinite which creates the sublime: "Farther expressions of infinity there are in the mystery of Nature, and, in some measure, in her vastness; but these are dependent on our own imperfections, and therefore, though they produce sublimity, they are unconnected with beauty"(4.91).

The contrast between beauty and sublimity which appears in these chapters was to have been a major subject of the sections on sublimity which Ruskin stated that he would place in the second volume (4.312-3l3), but which he left incomplete and did not finally include. But whether or not Ruskin omitted his proposed definitions and discussions of sublimity because they would have overtly conflicted with his theories of the beautiful, his uses of the terms "sublime" and "sublimity" throughout the last four volumes of Modern Painters demonstrate that he not only came to accept the opposition of the sublime and the beautiful, but that he also made use of the sublime, as had eighteenth-century theorists, as an aesthetic catchall, as a category into which he could place forms of aesthetic emotion excluded from his theories of beauty.

In the last four volumes of Modern Painters and his other writings Ruskin employed the terms "sublime" and "sublimity" in most of their usual eighteenth-century acceptations. The basic notion that sublimity is derived from a large, vast unified object appears frequently, as, for example, when he states that "a mass of one species of tree is sublime"(4.96), and that "the greater the number of objects which . . . become members of one another, the more extended and sublime is their unity"(4.96). This basic notion of the sublime as that which is simultaneously unified and vast appears throughout Modern Painters . In the fifth volume, for instance, Ruskin mentions a chapter in Michelet's work L'Insecte, which, he says, is "so vast in scope, and therefore so sublime"(7.232). The sublimity of magnitude, which he records in many of his Alpine drawings (see Plate 10), is the subject of an unused manuscript passage originally intended for the third volume of Modern Painters . There Ruskin describes a form of sublimity entirely dependent upon size for its effect:

In order to produce these peculiar impressions of sublimity on the human mind, certain degrees of this material largeness are absolutely necessary. No beauty of design in architecture, or of form in mountains, will entirely take the place of what may be called "brute largeness." That is to say, of the actual superiority in feet and inches, over the size of Humanity, our constant standard, the general truth being that . . . the greatest effect of sublimity will be produced by the largest truth which can be clearly manifested to us. (5.434)

Although Ruskin may not have been aware of it, when he derived sublimity from the relation of the vast object and the size of the human observer, he opposed sublimity to beauty almost as strongly as did Burke's physiological theory. Whereas Ruskin tried to derive both typical and vital beauty from divine nature and law, he here based sublimity on the size of man — "our constant standard." It could be further argued that since Ruskin is here concerned with an individual sense of relation to the sublime object, he introduces an [206/207] element of subjectivity. The sublimity of magnitude, then, is not, like beauty, the incarnation of permanent qualities, the shadow of God; it is, if the shadow of anything, the reflected shadow of man, the feeling produced when man compares himself with something greater than himself.

An Example of Mountain sublimity and

human scale in Ruskin's own drawings:

Chamouni. 1843. Reproduced as

frontispiece to Volume 2, Works.

[Not in print edition; clickon picture for

larger image.]

Ruskin did not finally include this section on sublimity of size in Modern Painters, Volume III, but he had previously made similar remarks in The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1848), and he continued to express these views throughout his career. For example, he frankly made man his standard for sublimity in the first of the Oxford "Lectures on Landscape" (1871), in which he argued that all landscape receives its interest from the presence — actual or imagined — of man. Holding up a small stone before his listeners, he explained that the most magnificently pictured Alpine scene, if unrelated to humanity, would be no more a landscape than his little piece of rock; for, he insisted, there is no such quality as bigness or littleness without reference to man. Similarly, there is "no more sublimity — per se — in ground slope at an angle of forty-five, than in ground level; nor in a perpendicular fracture of a rock, than in a horizontal one. The only thing that makes the one more interesting to you in a landscape than the other, is that you could tumble over the perpendicular fracture — and couldn't tumble over the other" (22.14-15). In other words, sublimity derives from an envisaged practical effect upon man: the size of a mountain or the angle of its slope become sublime only in relation to man's size, capacities, and potential movement. It becomes clear, then, that for a scene to be sublime, the spectator must imaginatively place either himself or another human being within it. [208/209]

This notion that the sublime requires an imagined human presence as an emotional "center" appears implicitly in Ruskin's many remarks on mountain sublimity. First of all, the mountain sublime is only partially produced by size; for, as Ruskin points out, it also comes from association of terror or danger. In the fourth volume, which is largely devoted to a discussion of mountain beauty, Ruskin writes of "sublime and threatening forms" (6.199), and mentions that "some sense of danger might always be connected with the most precipitous forms, and thus increase their sublimity" (6.135). Although Ruskin states that size has a role in the sublimity of mountains, he is more concerned with the emotional effects these mountains create in the observer, and it is, indeed, in terms of emotional effects that Ruskin most interestingly discusses the sublime.

Some of the emotions which Ruskin included under the class name "sublime" have little to do with his initial idea that sublimity is a name for the simple effect of greatness upon the feelings; and, although there is no evidence that he was influenced by Richard Payne Knight, Ruskin adopted a view of the sublime similar to that which Knight had presented in his Analytical Inquiry into the Principles of Taste (1790). According to Knight, "All sympathies, excited by just and appropriate expression of energetic passion; whether they be of the tender or violent kind, are alike sublime" (3rd ed., London, 1806, 371-72). Ruskin's statement that "impressions of awe and sorrow" are "at the root of the sensation of sublimity" (7.119) suggests that, like Knight, he believed all emotions, gentle as well as extreme and violent, were sublime. The "sad sublime"(6.296), which he mentions in describing a melancholy scene, is an example of this [209-210] gentler form of sublimity which was not described in the first volume of Modern Painters . Ruskin also appears to have abandoned his original theory that sublimity was the emotional effect caused by greatness when he wrote that "in the shock and shiver of a strong man's features, under sudden and violent grief, there may be something of [the] sublime"(4.203). Grief, although more intense than sadness, is not necessarily the effect of greatness — unless Ruskin later defined greatness of cause merely in terms of a resultant intense emotional reaction.

Although Ruskin does allow that mild or gentle feelings, such as sadness, are sublime, he usually uses the term "sublime" to describe violent emotions, such as awe, terror, and horror. Again intensity of the emotion, rather than a powerful efficient cause of the emotion, is the central factor. For example, Ruskin wrote that when certain effects of a mountain environment are combined, "the result [upon the inhabitants of mountain districts] is even sublime in its painfulness" (6.410). Even painfulness was sublime. Ruskin's editors note that brief manuscript passages exist for a section on the sublimity of fear and horror (4.371); so it is likely that Ruskin intended to change his original position even more and accept the idea that fear and terror have a role in sublimity. His remarks that the suggestion of danger increases the sublimity of a precipice (6.13 5) would seem to support the conclusion that Ruskin felt that fear and terror have a role in the sublime. He also seems to have associated other emotions, or other qualities which stimulate emotions (he did not always distinguish between them), with the sublime, and he may even have considered them sources of the sublime. In the fourth volume of Modern Painters he wrote of "sublime and threatening forms" (6.199) and also mentioned in the same passage the terrific, the strange, and the majestic. It is likely that these qualities and emotions entered Ruskin's later conceptions of sublimity. Ruskin also mentioned another kind of sublimity in the 1848 "Addenda" to the second volume, in which he wrote of Linnell's painting Eve of the Deluge that "its sublimity was that of splendour, not of terror" (4.334). We see here how casual Ruskin was in his use of the terms "sublime" and "sublimity," for whereas terror is an emotion, splendor is not; and, according to his own definition, it would have been proper to call the form of sublimity produced by splendor the sublime of admiration, awe, or wonder, or whatever he considered the effect of splendor upon the feelings. In view of the fact that Ruskin used these two terms in so many ways, it seems necessary to conclude that he not only reversed his earliest position, finally deciding that sublimity was a distinct aesthetic category, but also that, like previous writers, he used the sublime as an embracing aesthetic category in which he placed all forms of pleasing emotion; sorrow, grief, pain, horror, terror, awe, admiration, when contemplated, were all sublime.

Ruskin employs many of these meanings of the term "sublime" in The Seven Lamps of Architecture, which contains his most detailed formulation of a theory of sublimity. "The Lamp of Power," the chapter that explicates the "elements of sublime architecture" (8.110), warrants careful attention, since it not only grounds his uses of the term in a precisely formulated theory, but also applies this theory to the details of a sister art. [210/211] This chapter on the stylistics of a sublime architecture opens significantly, not with remarks on the art of building, but with a discussion of its effect upon the human mind:

In recalling the impressions we have received from the works of man . . . it often happens that we find a strange pre-eminence and durability in many upon whose strength we had little calculated, and that points of character which had escaped the detection of the judgment, become developed under the waste of memory.... In thus reverting to the memories of those works of architecture by which we have been most pleasurably impressed, it will generally happen that they fall into two broad classes: the one characterised by an exceeding preciousness and delicacy, to which we recur with a sense of affectionate admiration; and the other by a severe, and, in many cases, mysterious, majesty, which we remember with an undiminished awe, like that felt at the presence and operation of some great Spiritual Power. (8.100)

When Ruskin elucidated his theory of typical beauty he concentrated almost entirely upon elements in the beautiful that lay outside the mind of man. "The Lamp of Power," in contrast, opens with this discussion of the way we recollect in tranquillity emotions inspired by architecture. As we have already observed, when Ruskin writes about architecture, perhaps the most human of the arts, he always emphasizes its effects on man; and when setting forth an aesthetic theory concerning this sister art, he here dwells at length on association, memory, sympathy, and emotional effects. His emphasis that the most important reactions to the art of building occur deep within the mind and rise slowly into consciousness, bypassing the judgment, characterizes the subjective, human, pole of his aesthetic theories, and it is at this pole that he remains during this entire chapter.

For example, when continuing his essentially Burkean distinction between the two modes of architecture, he explains that their difference "is not merely that which there is in nature between things beautiful and sublime. It is, also, the difference between what is derivative and original in man's work.... [The original] depends for its dignity upon arrangement and government received from human mind, becomes the expression of the power of that mind, and receives a sublimity high in proportion to the power expressed" (8.101-102). Thus, whereas beauty in architecture derives from what exists external to man, architectural sublimity derives both from external nature and from the human imagination. Believing that "men cannot be taught to compose or to invent" (8.134), Ruskin only mentions briefly this highest element of imaginatively created power in architecture, and he therefore devotes most of his discussion to explaining how the architect can create sublimity by sympathizing "with the vast controlling powers of Nature herself" (8.102). Even when [212/213] writing of the way man draws upon natural sublimity, Ruskin does not chiefly emphasize qualities outside man. According to him, the structures which man erects should embody not only "worship and following" of the spirit of beauty but also that which builds earth's barren precipices into the coldness of the clouds, and lifts her shadowy cones of mountain purple into the pale arch of the sky; for these, and other glories more than these, refuse not to connect themselves, in his thoughts, with the work of his own hand; the grey cliff loses not its nobleness when it reminds us of some Cyclopean waste of mural stone; the pinnacles of the rocky promontory arrange themselves, undegraded, into fantastic semblances of fortress towers; and even the awful cone of the far-off mountain has a melancholy mixed with that of its own solitude, which is cast from the images of nameless tumuli on white sea-shores, and of the heaps of reedy clay, into which chambered cities melt in their mortality. (8.102-103)

Ruskin begins his comments on the natural sublime which the builder must emulate by writing of it as the incarnation, the bodying forth, of vast powers which lie outside man and which dwarf him. But as soon as he elaborates upon the sublimity of mountains and grey cliffs, he makes it apparent that nature considered purely external to the human consciousness does not much interest him. Instead, sounding much like the Associationist Alison, he holds up before us "this power and majesty, which Nature herself does not disdain to accept from the works of man"(8.103). Although he had been unwilling, two years earlier, to admit that human associations play a role in the beautiful, here he readily emphasizes the importance to the sublime of what the human imagination confers upon the external world. In "Tintern Abbey," a poem often quoted by Ruskin, Wordsworth had proclaimed his continuing love for nature as he apprehends it with eye and ear — "both what they half create, / And what perceive." In The Visionary Company: A Reading of English Romantic Poetry Harold Bloom comments of the phrase "half create," that though "the boundaries between man and nature have wavered, Wordsworth wishes to avoid the suggestion of the total absorption of nature into man" (Garden City, N.Y., 1963, 145).Ruskin's theoretical statements about beauty mark his attempt to absorb man into a nature symbolic of God, but in The Seven Lamps of Architecture he has reversed himself, now making nature part of man. For when he emphasizes that nature accepts from human works that sublimity "transferred by association to the dateless hills''(8.103), he makes it clear that nature colored by human thought, nature as it exists within the mind of man, most interests him.

Having thus explained the subjective character of the natural sublime, Ruskin proceeds to detail the ways in which the architect can draw upon its power. The central principle of the architectural sublime, insists Ruskin, is "that the relative majesty of buildings depends more on the weight and vigour of their masses, than on any other attribute of their design: mass of everything, of bulk, of light, of darkness, of colour, not mere sum of any of these, but breadth of them''(8.134). He first considers the sublimity of "mere size," explaining that while it might be thought impossible to emulate nature in this respect, such a conclusion does not follow from [214/215] the laws of human perception. Certainly, the architect must avoid contending with the size of natural objects: he must not build, for example, pyramids in the valley of the Chamouni. But as long as the human builder avoids such obvious comparisons of scale, he can achieve sublimity of magnitude: "The fact is, that the apprehension of the size of natural objects, as well as of architecture, depends more on fortunate excitement of the imagination than on measurements by the eye; and the architect has a peculiar advantage in being able to press close upon the sight such magnitude as he can command. There are few rocks, even among the Alps, that have a clear vertical fall as high as the choir of Beauvais; and if we secure a good precipice of wall, or a sheer and unbroken flank of tower, and place them where there are no enormous natural features to oppose them, we shall feel in them no want of sublimity of size"(8. 103-104). Since impressions of size depend largely on the imagination, the artist who can control the imaginations of his audience can thus achieve sublimity of size. All that the architect requires, says Ruskin, are the financial resources and a site sufficient to reach "that degree of magnitude which is the lowest at which sublimity begins, rudely definable as that which will make a living figure look less than life beside it"(8.105)

Once the designer of buildings has determined to create a structure marked by sublimity, he must follow certain stylistic principles. First of all, his building "must have one visible bounding line from top to bottom, and from end to end" (8.106). Ruskin remarks that many writers have held that for a building to show its size, the observer must take it in all at once, but he believes that his principle of the continuous bounding line is more central to the sublime style. He explains that the architect must take care not to break this bounding line with ledges or cornices that project too far, since they destroy the desired effect: "not because the building cannot be seen all at once, — for in the case of a heavy cornice no part of it is necessarily concealed — but because the continuity of its terminal line is broken, and the length of that line, therefore, cannot be estimated" (8.107). By thus emphasizing the effect of the building's profile upon our imagination, Ruskin applies to architecture the commonplace that the sublime object must be vast and uniform. He similarly draws upon conventional ideas of the sublime which emphasize uninterrupted regularity when he writes "that those buildings seem on the whole the vastest which have been gathered up into a mighty square" (8.108). Furthermore, the criterion of unbroken vastness requires that the architect in search of sublimity employ "breadth of surface" in his walls. In this manner, he can achieve the effect of "the flatness and sweep of great plains and broad seas"(8.1og). What material the architect uses in a large building matters little, says Ruskin, so long as "the surface be wide, bold, and unbroken" (8.109). To create the effect of sublimity in smaller buildings, such as cottages, the architect must employ a bold masonry like "the rude and irregular piling of the rocky walls of the mountain cottages of Wales, Cumberland, and Scotland" (8.1l3). Lastly, the architect must deploy large masses of light and shadow, a "Rembrandtism" (8.l 17) in building, since "after size and weight, the Power of architecture may be said to depend on the quantity (whether measured in space or intenseness) of its shadow" (8.1l6). His emphasis upon broad masses of shadow leads Ruskin to praise deep-[216/217] set windows, the Gothic "method of decoration by shadow" (8.128), and anything which creates a "broad, dark, and simple" (8.135) effect. According to him, "It matters not how clumsy, how common, the means are, that get weight and shadow — sloping roof, jutting porch, projecting balcony, hollow niche, massy gargoyle, frowning parapet; get but gloom and simplicity, and all good things will follow in their place and time" (8.135). Both Ruskin's citation of these architectural details and his major emphasis upon massing of light and shadow reveal that he believed this art must work with height, breadth, and depth, shaping space to create a sense of the sublime. "The Lamp of Power," in other words, offered Victorian England a stylistic alternative to what Nikolaus Pevsner has described as the characteristic English emphasis upon linearity and "beautiful surface quality" (The Englishness of English Art, London, 1956, 90. See also, pp. 81-106). Although Ruskin has been accused of being both insular and little concerned with the visual appearance of architecture, his remarks in this chapter on power demonstrate that he recognized, as did few architects of his own age, the essential nature of architecture as a three-dimensional art.

Twentieth-century architects have agreed with Ruskin, and, although many of his statements about beauty in architecture seem concerned with a kind of building quite foreign to our own century, his characterizations of sublimity, on the other hand, anticipate much of the modern movement. Both the work of Gropius, who considered himself a follower of Ruskin, and of Wright, who early knew all of Ruskin's major works, often seem to embody his conceptions of the architectural sublime: in particular, aspects of Gropius's 1914 model factory in Cologne and Wright's early Larkin building and late Guggenheim Museum embody Ruskinian principles — whether or not they betray a direct influence.

Ruskin's examples of architectural success and failure enable us to envisage even more clearly his conceptions of sublimity in building. According to him, "St. Peter's, among its many other errors, counts for not the least injurious its position on the slope of an inconsiderable hill" (8.103), an error in siting which lessens the sublimity of the church. Moreover, the recessed dome of this building, which from most vantage points does not allow the spectator to perceive the structure as a uniform mass, shows how a broken profile also destroys a potentially sublime effect. From the evidence of St. Peter's and the Duomo in Florence Ruskin concludes that church designers who want to achieve sublimity (as opposed to beauty) cannot employ domes or towers over their central portions, but instead should place high towers either at the west end or "better still, detached as a campanile" (8.107). When he emphasizes the importance of "one bounding line from base to coping" (8.107), he cites the Palazzo Vecchio as an example of a secular building which thus correctly employs a tower. In addition, this building's size, shape, siting, treatment of walls, and massing of shadow would all seem to exemplify the Ruskinian notion of architectural sublimity. Similarly, the Castle San Angelo in Rome and the Venetian Ducal Palace successfully employ a broad expanse of wall surface, correct siting, unbroken bounding lines, and a shape approaching the square.

Ruskin finishes his discussion of architectural sublimity, as he began it, with reference to the nature of mental impressions, emphasizing in both instances the slow yet inevitable workings of memory and emotional reactions. The chapter, which opens with an examination of the audience's reaction to architecture, closes by explaining the architect's reactions to his environment. According to Ruskin, the buildings the young, developing architect sees around him cripple his capacity to create powerful works:

Of domestic architecture what need is there to speak? How small, how cramped, how poor, how miserable in its petty neatness is our best! . . . I know not how we can blame our architects for their feebleness in more important work; their eyes are inured to narrowness and slightness: can we expect them at a word to conceive and deal with breadth and solidity? They ought not to live in our cities; there is that in their miserable walls which bricks up to death men's imaginations.... An architect should live as little in cities as a painter. Send him to our hills, and let him study there what nature understands by a buttress, and what by a dome. (8.136)

Ruskin, who will not accept any specific proportional canon, holds that the architect must learn to compose powerfully by sympathizing with the power, the energy, the life of nature. Like Frank Lloyd Wright after him, he believes that the architect must therefore flee the city, which stifles our sympathies, and dwell amid the sublime natural features of earth. Once again in our examination of Ruskin's aesthetics we return to what we may call the primal, or archetypal, situation which lies at the heart of so much of his writings: man, whether artist or spectator, stands alone in the presence of nature, receiving emotional reactions that strengthen his capacities for living. His notions of the development of the architect, like his notions of beauty, sublimity, and the moral effects of art, demand that man exist, if only on rare occasion, in a felt relation to the exterior world. His writings on the sublimity of architecture, the pre-eminently human art, emphasize that man himself must be the source of much of these vitalizing emotions and sympathies. Although mountain peaks, broad plains, and vast seas must exist outside man to provide sources of life, man's associations and man's sense of self must finally create the sublime.

Last modified 6 May 2019