n order to understand the publishing business as it affected Thackeray, one can follow Vanity Fair through production, accounting for prepublication advertising, the cost of paper, the cost of printing, everything associated with printing and binding the serial, and the way in which the publisher paid itself as well as the author. In order to focus on a production process that can no longer be reconstructed from accurate personal accounts, inferences from the printed books and data from the account ledgers must be used. Yet beginning with the printed books can easily cause confusion, for some of the standard bibliographical descriptions reveal ungrounded assumptions about the process.

For example, from time to time booksellers' catalogues offer Vanity Fair in parts with descriptive notes and references to Henry Van Duzer's 1919 description of his Thackeray library [Van Duzer, pp. 123-32]. Occasionally the descriptions refer to other known copies of the novel for comparison. One such catalogue refers to "the Austin copy" as "the finest copy of 'Vanity Fair' ever offered at auction in America" and ends its headnote on the current [153/154] offering as "ONE OF THE TWO FINEST COPIES EVER OFFERED AT AUCTION IN THIS COUNTRY. " [proofs from an unknown auction catalogue in the Lilly Library, Indiana University] Who owns the finest copy of Vanity Fair is a question likely to interest book collectors more than literary critics or book production historians. And as long as fineness is determined by references to the condition of the wrappers and the priority of advertisements unconnected with the novel's text, it will remain a question of little importance to the critic. But it is an important question to both collectors and critics when the significance of the connection between fineness and the text is explored in the production processes.

The basics are, of course, well known: the first edition consists of twenty numbers in nineteen separate installment parts, each with thirty-two pages of text, additional leaves of advertisements, and printed yellow paper wrappers.14 The last installment contains numbers 19 and 20. The first number was published on 1 January 1847, and the final double number was published on 1 July 1848. Following completion of the serial issue, leftover sheets from that issue along with newly reprinted sheets from the same typesetting were used for publication of the novel in one volume. The publisher's accounts record multiple printings of this edition and continuous availability of the novel in parts and book form throughout the 1850s and 1860s.

This summary of the production of Vanity Fair gives a false impression of simplicity. Both scholars and book collectors have operated under certain naive assumptions that need dispelling — to wit: the idea that any given physical copy of Vanity Fair whether in parts or volume form, might as a whole belong to a single printing (the production process of mid-nineteenth-century serialized novels makes this as likely to be untrue as to be true); or the idea that the "printing," "issue," or "state" of the text of a serialized novel can be ascertained by reference to points in the wrappers. Regardless of the literary significance of the textual variants in Vanity Fair, their existence and distribution have an important hearing on the question of fineness or priority. But the variants do, also, have literary significance and must attract the critics' notice. Among the printings within the first edition, there are 210 variant readings, of which 150 are [154/155] substantive, 17 being the addition, deletion, or substitution of passages ranging in length from three to seventy-five words.

It would seem, for example, of some small importance to the literary critic to know that originally Mr. Jos Seeley in Vauxhall Gardens is referred to as a "fat bacchanalian" but that second thoughts led to the deletion of that description15, or that Miss Crawley had originally signified her intention of dividing her "fortune equally" between Sir Pitt's second son and the family at the rectory, but that in revision the fortune is described merely as an "inheritance" to be divided without reference to proportion (p. 72, 1. 25). And it must be of some interest to the followers of Becky's fortunes that in the original text the reason Colonel Crawley, though governor of Coventry Island, could settle on her only £300 a year (out of an annual income of £3,000) was that his revenues went to the "payment of certain debts and the insurance of his life," but that later the reference to life insurance was deleted (p. 79, ll. 7-8).

Indeed, both the critic and the printing historian stand to benefit as much as the book collector from the effort to determine who owns the finest copy of the first edition of Vanity Fair; for though there is probably no satisfactory answer, the attempt at one requires attention not only to book-collecting values but to the complex printing history of the book and the artistic effects ofthe author's continued interest in the composition

of the work during the printing processes. It is possible to determine when those 210 variants first appeared in the text, who was responsible for them, and finally what significance they have to an understanding and assessment of the novel.

As David Randall has pointed out, there are five areas of concern for parts-issued books: front wrappers, back wrappers, inserted advertisements, plates, and text [Randall, p. 96]. For Vanity Fair, by far the greatest interest to date has been lavished on the first three — the parts the author had the least to do with. Booksellers continue to identify their copies of Vanity Fair by reference to readings on the wrappers and by one or two famous "points" in the text, which are not in fact points, one of the most often used "points" remaining unchanged throughout all printings of the first edition.17 But [155/156] these five concerns are merely the discrete parts of the product. Taken together they are the corporate results of the activities of publishing, printing, binding, and marketing, each of which affect the five-part product. Synthesizing all the evidence makes it possible to provide a satisfactory guide to the effects that its production history had on the novel, the specific result of production represented by a given copy of the book, and the significance that the vicissitudes of production have for the student of the text and for the book collector.

The basic task in producing Vanity Fair was to typeset thirty-two pages a month on two octavo sheers hearing sixteen pages each in such a way that all thirty-two pages would be decently occupied by letterpress or illustration and so that the last page of the last chapter of each number would end a respectable way down the thirty-second page. Important incidentals to this task involved preparing the yellow paper wrapper which had a dated and numbered title as well as an illustration on the front and advertisements of various sorts on the front and back of the back cover. A four-page advertiser was printed and added at the end. The two sheets of text and one of advertisements were then folded, the wrapper placed around them, and they were sewn by "stabbing." Having manufactured the installment, the publisher had to distribute it for sale 18.

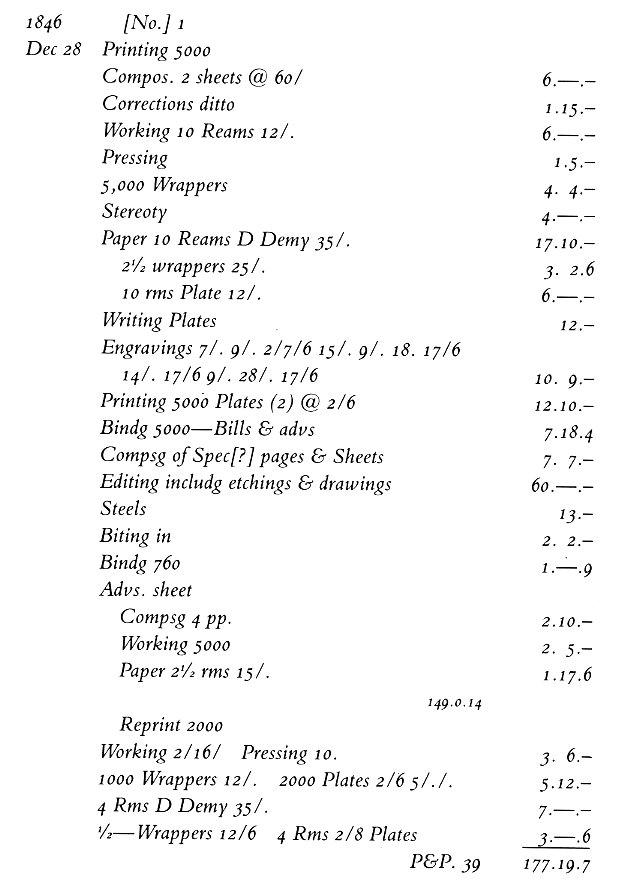

The production records for Vanity Fair were kept in several books, two of which are of primary importance and tedious complexity.19 The first is an unlabeled book that details the production costs of serial publications by Bradbury and Evans. Totals from this book were carried over to the second, labeled "Paper and Print," which was the final accounting book for the firm. The first unlabeled ledger may well be a book made up from a no longer extant daily ledger, for the production costs detailed in the unlabeled book seem to summarize certain categories of costs. It is possible, however, that the sources for the entries in this book were individual billings. [156/157] The entries for incidentals and advertising relating to Vanity Fair began on 21 November 1846, though an initial attempt to begin publication of the book took place in March or April.

The numbers in the column just to the left of the cash amounts column on the right are something of a mystery except for number 39 preceding the total; that is the page number in the second account book which is titled "Paper and Print," indicated in this entry as the "P&P Book." The Paper and Print book is the book where all the costs and income related to Vanity Fair are gathered and summarized. That is also the book in which the publisher figured its own income. If the other numbers in this column also refer to page numbers, they are references to ledgers no longer extant.

What these seven months of entries for incidentals and advertising show is the amount of effort that went into promoting the sale of Vanity Fair during the first six months of its run, which began on 1 January 1847. The costs may not seem much, but the effort of composing, printing, and distributing 30,000 prospectuses and 40,000 (or perhaps 70,000) bills (some of which were stitched into the serial parts), and 3,000 posters, which from the cost (£17.17) must have been in two colors each, seems [157/158] quite satisfactory if not extraordinary. Advertisements are also entered separately in the Paper and Print book and must be additional to those recorded in this unlabeled listing.

Production costs for each number were detailed in the same unlabeled book just a few pages after the incidentals entries.

Production of 7,000 copies in two printings of number 1 of Vanity Fair cost £177.19.17. These costs are to be understood as follows: the [158/159] compositors setting type for two sheets (i.e., thirty-two pages) received 60s.a sheet, which comes to £6. Corrections or alterations in the typesetting cost £1.15. Working ten reams of paper (i.e., 5,000 sheets) at

12s. per ream equaled £6. Five thousand copies of the number resulted because each double demy sheet produced two octavo sheets for the book. "Pressing," an operation clearly separate from "working," but which I cannot explain, cost £1.5. Five thousand wrappers or covers for the part cost £4.4. Casting the stereotype plates cost another £4. Paper for the text of the novel, ten reams of double demy at 35s. a ream, cost £17.10. Two and a half reams of wrappers at 25s. came to £3.2.6. (In order for 5,000 wrappers to be produced from 2 ½ reams, each sheet would have to contain four wrappers. To achieve this arrangement, the wrapper need be composed only once, and one stereotype cast made. These two sets of type, mounted all at once on a press and printed by the work-and-turn method, would produced four identical wrappers on each sheet.) The fact that ten reams of paper were required for the steel etched plates indicates that only two illustrations could be printed at a time. This paper was heavier than the text paper and cost 12s. a ream, or £6 for the number.

Writing on the steel etched plates cost 12s. This was probably done by a coppersmith; there is a charge for a coppersmith's alterations for the second number.20 Twelve wood engravings also were paid for. While Thackeray did his own drawings, he did not engrave the woodblocks himself. Not all the engravings paid for were necessarily used in the book, a possibility that lends itself to the notion that engravings embedded in the text were used or not according to the demands of last-minute adjustments to the length of the number, each of which had to be precisely thirty-two pages long. The steel plates added a significant expense to the number; it cost twice as much to print 5,000 copies of the plates as it did to print 5,000 copies of the text, £12.10. Binding the number, including the bills and advertisements for the "advertiser" that went with it, cost £7.18.4. The cost of printing the bills was an entry on the incidentals page, and so was not repeated here,

That the next entry involved composing of type is clear enough, but just what was being composed is not clear. There is no corresponding entry in the accounts of other numbers. The amount, £7.7, is just over that for composing the first number. I think it is the charge for the first typesetting of number 1, undertaken in March or April 1846. That [159/160] typesetting was abandoned after it bad been proofread at least once and corrections made for a second set of proofs. The decision to abandon it stemmed at least in part from the difficulties Thackeray had in adjusting its length to the thirty-two-page requirement. That attempt, incidentally, had no engraved illustrations embedded in the text to help in those adjustments [cf. Shillingsburg, Vanity Fair, pp. 651-54].

A quaint feature of the Vanity Fair accounts is that the payments to Thackeray as author and illustrator are listed as "Editing including etchings and drawings." Thackeray received £60 per number. His payments are included as a cost of production. This is important to note; the cost of these payments would have to be recovered before any profits began to show. The steel plates cost 13s; biting in the drawing — which Thackeray would have etched directly onto the coated plate — cost £2.2. The next entry is a bit of a mystery; £1.0.9 for binding 760 looks like a binding order for 760 copies of the part, billed at a fraction less per copy than for binding the 5,000 copies. But there were no more copies to bind, unless this refers to a partial binding order for the 2,000-copy reprint reported farther down the column. Later in the long-drawn-out life of the first edition, binding orders for small numbers are common.

An advertisement sheet of four pages cost £2.10 for composing type, £2.5 for working at the press, and £1.17.6 for 2 ½ reams of paper (each sheet, again, producing two copies of the advertiser). The next entry, "149.0.14," is tucked into the record in smaller handwriting as a notation and serves as a subtotal (inaccurate by £10) for the production costs of number 1 before adding the costs of the reprint.

The 2,000-copy reprint cost £3.6 for working and pressing (there was no composition cost because the stereotyped plates were used), £5.12 for wrappers and plates, £7 for text paper, and £3.0.6 for wrapper and plate paper.

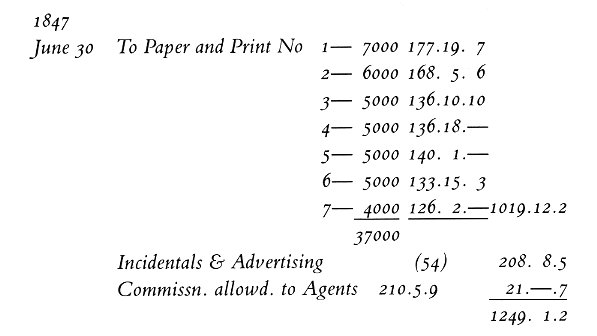

The initial production cost for number 1 (up through June 1847) came to £177.19.7, including the author's fee. This figure and the total costs for incidentals and advertising for November 1846 through June 1847, £208.8.5, detailed in the unlabeled ledger, were carried to page 39 in the Paper and Print book where they became single entries in a 30 June summary of costs. The total cost for each number of the serial was similarly computed and carried over to the Paper and Print ledger.

This ledger has debits and credits on facing pages. The debits or costs for Vanity Fair are listed on a verso. [160/161]

The first entry is the £6177.19.7 just detailed for the production of 7,000 copies of number 1. The next six entries are comparable costs for the production of the next six numbers produced up through 30 June 1847. The incidentals and advertising costs from page 54 in the unlabeled book have already been discussed. The commission allowed to agents (probably wholesalers, but possibly traveling salesmen) is figured at 10 percent of £210.5.9 — a sum that does not appear elsewhere in the ledgers, nor have I been able to figure out how it was determined. The commission to agents appears to be a separate arrangement from the one that is recorded on the credits page in which the price of numbers was discounted 25 percent from a shilling down to 9d. The production costs for the first seven numbers of Vanity Fair during the first six months amounted to £1,249.1.2 including seven payments of £60 each to Thackeray.

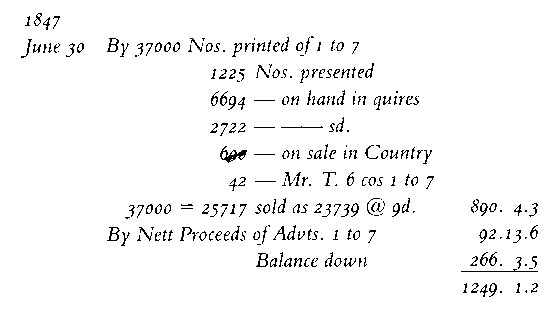

The credits for Vanity Fair appear on the facing recto.

the 37,000 copies of numbers 1 to 7 printed, 1,225 (the equivalent of 132 copies of the first seven numbers) were given away as presentation [161/162] copies and for review; 6,694 (about 956 copies of the seven numbers) were still in hand unsewn (in quires); 2,722 were still in hand already sewn or bound; 600 were on consignment to agents in the country; and 42 (6 copies of the seven numbers) had been given to Thackeray. The other 25,717 numbers (3,674 copies of the seven numbers) had been sold.

Two kinds of discounts appear here. The 25,717 copies were sold as 23,739 (i. e 1, 978 thrown in free, or a 7.7% discount), and these were sold at 9d. each rather than the shilling retail price (another 25% discount). Total income in the first six months from sales came to £890.4.3 (though it must be remembered that these figures represent at most the first day or two of the sale of number 7). Income from advertisements included in the number came to £92.13.6, leaving a shortfall of £266.3.5.

By the end of the next six months, production costs for numbers 8-13 had amounted to £771.2.9, and incidentals and advertising cost £31.16.9. An error was detected in the credits for the last six months, since the price per number was 8 ¾ d. rather than 9d, so £124.14.7 was added to the debits. Agents' commissions were allowed on £159, which amounted to £15.18, and an undetailed charge for "Assistance in Nos. 6 & 7" came to £2.2.

The final entry on the debits page for the July to December 1847 accounting is a "Comm. to Publishers on 1813.3.3" which was figured at 10 percent and came to £181.3.4. The corresponding credits page shows that sales brought in £773.2 and proceeds from advertisements came to £57.3.6, a gross income of £830.5.6. The sum of this income and that of the first six months, £982.17.9, is £1,813.3.3. Bradbury and Evans figured the firm's commission as 10 percent of gross income of sales and the net income of advertising. Thus, at the end of the first year of publication, after thirteen installments, Vanity Fair was running £467.18.4 in the red, though it had paid its author £780 and its publisher it £181.3.10.

The story of production costs and income had yet to reach a climax. The financial accounts of Vanity Fair turned from red to black in 1848. There was, apparently, no half-yearly accounting, since the Paper and Print book shows sums for the whole year. In addition to the £462.18.4 debt remaining from 1847, production, incidentals, agents' commissions, etc., for numbers 14-20 came to £2,162.15.8. This amount includes the £420 paid to Thackeray for those numbers and £338.11.5 paid to the publisher as its 10 percent commission figured on an income for the year of £3,385.14.5. Not only did income in 1848 make up for the deficit, but there was a surplus of £760.0.3.

None of this apparent surplus reached the author. In 1849 the publisher paid itself commissions of £46.18.4 and £16.8.5. The surplus on [162/163] hand increased to £1,003.10 after the expenses of reprinting the whole book twice and various numbers a third time had been met. In the first six months of 1850, production and incidental expenses fell to £48.2 (which included £17.11.4 to the publisher as commission) while income came to £175.13.3. This brought the surplus balance to £1,179.3.3. By this time

Thackeray had earned £1,200, which had been paid to him in advance at the rate of £60 a month while he was writing the novel. His last income had been credited to him in July 1848. Bradbury and Evans matched that sum for the publisher's share in January 1850, more than wiping out the surplus. The total publisher's commissions by this time had amounted to £600.15.10. Thus, as of 1 July 1850, Thackeray had made £1,200; Brad-

bury and Evans had made £1,800.15.10; and the account was £68.18.9 in the red. This accounting procedure was relatively common. It applied to Thackeray's arrangements with Smith, Elder as well. By equaling the score, so to speak, the way was paved to begin profit sharing.22

In the last half of 1850, the shortfall in the Vanity Fair account was reduced to £49.12. 10, and in the first six months of 1851 the book showed its first sharable profit, £39.13.6 divided equally between author and publisher, The publisher continued to draw its to percent on sales before figuring profits, but for years publisher and author reaped small amounts of profit at six-month intervals: £12.19.8 each in December 1851, £28.3 each in June 1852, £30.12.4 each in December 1852. The income then dipped to £1, £2, or £3 in some years but jumped to £33.10.5 each in the first six months after Thackeray's death. It is not a macabre note to strike, since Thackeray repeatedly said he was working to leave his girls £10,000 apiece, and his copyrights — weak as some of them were — were among the greatest of his possessions.

Some traditional collectors of Vanity Fair might think much of this investigation unnecessary. One assured me that a useful bibliography is one that identifies the printings in a simple straightforward way for book collectors. But identifying the printing or state represented by any given [163/164] copy of Vanity Fair is seldom possible. It is often possible to identify the printing or state of each sheet or gathering within a given copy of the book, but most copies of Vanity Fair as wholes represent hybrids or mixtures of sheets from different printings, the natural result of the methods of manufacturing and marketing the book.23 When each monthly part was published, a certain number of copies of the part were printed from type. As the stack of printed sheets for each number dwindled in the bindery, it was replenished by reprinting. The result was that some parts were reprinted more often than others (see Appendix C, chart 1). The book was available in parts for years after it had also become available in book form, and the book form itself was bound in small lots as needed for distribution; hence sheets from one printing can appear indiscriminately mixed with sheets from other printings in any given book — regardless of its present form, whether parts or volume. If a particular copy of the book has an early title page and prefatory material, the rest of the book may yet consist of sheets printed late or a mixture of early and late. Even if the issue of parts had ceased once the book as a whole became available, one need only be reminded that eighteen months elapsed between the printing of number 1 and the printing of the title page and that, according to the publisher's records, during those eighteen months numbers 1 and 7-13 were each reprinted once.

Though I have been able to identify the order in which variant readings were introduced to the text and have given them in that order in the appended table (Appendix C, chart 3) they may appear in confusing disorder in any given copy of Vanity Fair. Thus, in using the variants lists as a means of identifying a given book, each gathering must be identified separately. Furthermore, the Vanity Fair owner must be warned that the difference between parts and book-form issues was created by the bindery, not the press. In other words, the mere fact that a copy was issued in parts is no guarantee that the text is an early printing, nor does the fact that a copy is in hook form mean that it is composed of later printed sheets.

Following the completion of the parts issue on 1 July 1848 and during the succeeding fifteen years, Bradbury and Evans issued the first edition of Vanity Fair continuously in parts and volume forms. Each monthly part was printed at least six times, twelve parts were printed seven times, and two parts were printed eight times — prepared according to the schedule in [164/165] Appendix C, chart 1. The novel was stitched into parts and bound in book form for distribution according to the schedule in Appendix C, chart 2.

1. The first printing of each number was run off from standing (movable) type. Positive identification of printings from type can be made by measuring the length of any printed line extending from margin to margin. If the measurement equals or exceeds 3 13/16 inches (9.7 cm), the page was printed from standing type; copies printed from stereotyped plates measure 3 ¾ inches (9,6 cm) or less.

States of the first printing were created when certain changes were effected in the standing type before stereotyped plates were cast. Though it is not clear whether these changes were stop-press corrections producing two states of the first printing or if they represent second printings from type, the former seems the more likely in view of certain evidence concerning the stereotyping, The changes in the standing type are listed in columns 1 and 2 of Appendix C, chart 3. In one instance, that of signature X in number 10, three states of the first printing are distinguishable (see chart 3, entries 309.3 and 309. 11).

In the publisher's account books, charges for stereotyping were entered at the same time as those for initial composition and corrections, and it is conceivable, perhaps even probable, that the stereotypes were cast immediately after the first printing from standing type. If that were the case, one would expect to find relatively commonly copies of Vanity Fair in parts with numbers 1 and 7-13 printed from stereotypes since these numbers were reprinted months before their reissue in book form (see Appendix C, chart 1). in fact, however, both the normal complexities of original production and the rapacity of unscrupulous bookmen have produced copies of Vanity Fair in parts with sheets printed from stereotypes. An egregious instance of the latter is the Heineman copy in the Pierpont Morgan Library, which was expertly repaired so that only careful examination reveals that seven of the gatherings were made up by combining pages from at least two different copies — one printed from type and one from stereotyped plates — and that three additional whole gatherings printed from stereotypes were probably supplied surreptitiously: a classic case of collecting wrappers and advertisements rather than texts. However, not all "mixed copies" are aberrations; the publisher's records show that Vanity Fair was always available in parts so that as the years went by, new sold parts would contain late-printed sheets. Similarly, copies in volume form sometimes contain early, maybe first-printing, sheets either as a normal result of binding schedules or because some purchaser of early [165/166] parts had his copy rebound in volume form. Nevertheless, certain copies (not all in parts) composed mostly of sheets printed from type have been noted with numbers 1 and 7-11 both printed from stereotyped plates and sharing all the readings characteristic of the last state of the printing from type. Not only does this pattern correspond with the publisher's records, but it demonstrates that the major alterations in Vanity Fair, for these numbers at least, were effected after stereotyping. It is likely that similar copies of the book in parts also exist with numbers 12-13 printed from stereotypes but with readings corresponding to the final state of the first printing.

It is misleading to speak of a second printing of Vanity Fair, for not all parts reached a second printing at the same time. There was, nevertheless, a short time in which the publisher was producing books with a characteristic combination of first-printing sheets and second-printing sheets which it is tempting to refer to as a second stage of production.

2. The second printing of numbers 1 and 7-13, apparently issued in combination with first-printing sheets of the rest of the book, was printed from stereotyped plates but shares the readings of the final state of the printing from type (see column 3 in Appendix C, chart 3). Numbers printed from stereotypes but with readings agreeing with the printing from type can be distinguished from type-printed numbers by the measurement described above (i.e., type-printed pages measure 3 11/16 inches or more horizontally from margin to margin while stereotype-printed pages measure 3 ¾ inches or less). This second printing of numbers 1 and 7-13 can sometimes be distinguished from other, later stereotype printings by the readings in column 3 of Appendix C, chart 3.

Though the publisher's records give no clear indication of when the majority of the substantive variants were introduced, the existence of numbers 1 and 7-11 printed from stereotypes with unaltered readings proves conclusively that changes in those numbers postdate the stereotyping and suggests a similar pattern for the rest of the book.26 In addition, the [166/167] evidence of machine collation, though inconclusive, seems to suggest that in numbers 2, 3, and 5 a few changes not actually noted in any copy of the book printed from type may in fact predate the stereotyping.27 It is possible that these changes were made in standing type which was not then used again before the stereotypes were cast and that the further changes, made after stereotyping, were effected in the stereotype plates before they were used the first time. Hence, there may never have been copies of the book with the earlier changes only. The importance of the machine-collation evidence is that is suggests a chronology of changes and supports the notion that Thackeray's interest in changing the text was continuous, not merely a onetime or haphazard concern. The changes that appear to predate stereotyping are all corrections or alterations of some magnitude and are probably authorial.

2B. The second printing of numbers 2-6 and 14-20 was made from stereotyped plates incorporating considerable alteration and seems to have occurred at about the time of the third printing of numbers 1 and 7-13. See Appendix C, chart 1, for the rapidity of reprinting during the eight months following the serial's conclusion (July 1848 through February 1849). This second printing of numbers 2-6 and 14-20 can be distinguished from the first printing by the measurement indicated above (i.e., the first printing is from type, the second from stereotypes) and by the readings listed in chart 3, column 3.

3.The third printing of numbers 1 and 7-13 was made for the most part from corrected stereotyped plates. However, the "correction" of signature [167/168] Y entailed the removal of a woodcut from the text. The result was that the text from that point to the end of the chapter had to be moved up 9.7 centimeters. Rather than trying to cut and move stereotyped plates, the printers reset the whole of pages 336-40. Thus, the first pages of the next signature, Z, are also reset. At least one printing, probably the third, was run off from corrected plates except for pages 336-40, for which reset type was imposed along with plates. The readings characteristic of this printing are recorded in chart 3, column 4.

4. The fourth and later printings by Bradbury and Evans are not distinguishable from one another and are only occasionally identifiable at all. The publisher's records show six printings for each of the nineteen parts, seven printings for twelve parts, and eight printings for two parts. Signatures Y and Z are again significant, for the pages printed from type in the third printing were then stereotyped for subsequent printings, and though there are no distinguishing readings, the type-page measurements indicate stereotyping.

The title page, printed with part 19-20, is the only page that can be distinguished in more than four printings. According to the publisher's records, the final part (containing numbers 19-20, the preface, and title page) was printed seven times by Bradbury and Evans before Smith, Elder and Company acquired the stereotypes and back stock in 1865. The Bradbury and Evans printings occurred three times in 1848, once each in 1849 and 1855 and twice in 1864. Unlike the text, the title page seems to have been reset for each printing, and six different settings have been identified. Though it is impossible to determine the precise order in which the title pages were prepared, it is beyond question that the first one given in Appendix C, chart 4, is the first printing. It seems likely that the two printings dated 1849 precede some if not all the others dated 1848 because the books they belong to have some readings predating those in copies with the 1848 date. However, the mixtures of early and late sheets by the bindery makes it impossible to use the state of one sheet as evidence for the state of other sheets in the same book.

Since each of the title pages was entirely reset, the apparent carry over of a characteristic from one to the next would be fortuitous, not indicative of chronology.

When Smith, Elder and Company acquired the copyrights and the back stock of stereotypes and printed sheets from Thackeray's other publishers in July 1865, they acquired from Bradbury and Evans 5,000 copies of "various numbers" of Vanity Fair in parts and 2 copies bound up. Over the next eight months they printed enough "various numbers" to [168/169] bring the total to 17,392 which were made into 865 copies of the book bound in cloth with 92 numbers left over. Though I have not yet encountered a copy dated 1865, a charge for new titles was entered in the account books for November of that year. A copy dated 1866 is at the Simon Fraser University Library.28 The records also show an August 1868 printing of 250 copies, again with a new title page dated 1868; there is a copy (not personally examined) in the British Library. That Smith, Elder reprinted the first edition of Vanity Fair in 1868 (the same year in which they brought out an entirely new edition of the book as part of a collected edition of Thackeray's works) is a clear indication that Smith saw separate rather than overlapping markets for the various formats of a single title.

What does it all mean? For the book collector the historical record reveals the true nature of the copies of Vanity Fair one already owns, and it establishes a range of representative copies that can be added to one's collection. For the historian of printing, the record with its combination of evidence from publisher's records and the books themselves confirms the complexity of the economic, technological, and artistic confluence that commercial book publishing had become. For the textual editor the implications are patently clear: it takes a lot of collating to find the true state of textual variation. For the literary critic and student of Thackeray's works, the record of variants provides a basis for further understanding Thackeray's attitude toward his text and supplies evidence leading to a clearer understanding of his concerns in the novel. Some changes seem to have relatively obvious motives: the elimination of Dobbin's lisp (all but one instance) at pages 50.18 and 105.18-19 was clearly intended to improve the image of the book's only gentleman. And the deleted reference to life insurance at 579.7-8 was the mere correction of an error, since at 501.3-4 Rawdon was unable to qualify for life insurance at all. But other changes suggest more subtle motives. Why, for example, did Thackeray find it inappropriate, at 50.1up, to call Jos a "fat bacchanalian"? And why, at 75.29, did he change Lady Muttondown to Lady Southdown and then decide, at 500.35, that is was also inappropriate to refer to Lady Southdown as Lady Macbeth? Some changes can be understood by reference to the manuscript, as in the case of the deletion of the sentence at 40.10-11: "And what can Alderman Dobbin have amongst fourteen?" Though vaguely and puzzlingly reminiscent of St. John's account of the feeding of [169/170] the five thousand, the sentence is unclear. The manuscript has "leave," not "have," a perfectly clear reading which does not recall the miracle feeding at all. But perhaps there was self-censorship, not correction, in the fact that Mrs. Blenkinsop, at 55.114-15, was no longer allowed to opine to Pinner, apropos of Becky, that governesses are "neither one thing nor t'other." If nothing else, the alterations focus attention on passages that were, somehow, not right and for which the new readings are, somehow, better.

Last modified 30 November 2021