[Revised and adapted from the author's article of the same title from Women's Studies Forum No. 8 (March 1994), Kobe College Institute for Women's Studies, Japan. Click on the illustrations to enlarge them and usually for more information about them.]

ore interesting, however, than either the competent or the hopeless

housekeepers of Victorian fiction, are those who try to resist the restrictions imposed on them by contemporary mores, those who clearly "need

exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts as much as their

brothers do." These are the girls who, as Charlotte Brontë says, "suffer

from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation" (Jane Eyre, 141) — and make us aware of their frustrations. Olive Schreiner's Lyndall certainly does that, declaring: "We wear the bandages, but our limbs have not grown to them; we know that we are compressed, and chafe against them"

(The Story of an African Farm, 189). Such are the unspoken sentiments of a

number of other heroines who, like Clara Middleton in George Meredith's

The Egoist, possess "a spirit with a natural love of liberty" (44). These gain

our sympathy not by revelling in the service of their loved ones, nor by

suffering from their own inadequacies, but by trying to keep hold of their

individuality. Time and again we see girls mutely or openly protesting

against what is considered to be their appointed lot; some, like both Jane

Eyre and Clara Middleton, earn at least the right to choose their own path

in life, even if what this means is accepting a husband on their own terms.

ore interesting, however, than either the competent or the hopeless

housekeepers of Victorian fiction, are those who try to resist the restrictions imposed on them by contemporary mores, those who clearly "need

exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts as much as their

brothers do." These are the girls who, as Charlotte Brontë says, "suffer

from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation" (Jane Eyre, 141) — and make us aware of their frustrations. Olive Schreiner's Lyndall certainly does that, declaring: "We wear the bandages, but our limbs have not grown to them; we know that we are compressed, and chafe against them"

(The Story of an African Farm, 189). Such are the unspoken sentiments of a

number of other heroines who, like Clara Middleton in George Meredith's

The Egoist, possess "a spirit with a natural love of liberty" (44). These gain

our sympathy not by revelling in the service of their loved ones, nor by

suffering from their own inadequacies, but by trying to keep hold of their

individuality. Time and again we see girls mutely or openly protesting

against what is considered to be their appointed lot; some, like both Jane

Eyre and Clara Middleton, earn at least the right to choose their own path

in life, even if what this means is accepting a husband on their own terms.

The encouragement afforded to such characters reveals what might be called the hidden agenda of many Victorian novelists, and not only the women among them. Even those who uphold the old order are sometimes swayed by it. The most rabid traditionalist, like the anonymous author of England's Daughters: What is Their Real Work? (published in 1870), who at one point declares that "no woman can educate a boy of good abilities, over ten, or twelve years of age" (8), can scarcely avoid putting in a word or two for the downtrodden. (This anti-feminist deplores the treatment of governesses, whatever their shortcomings.) As both Charlotte Brontë and George Eliot discovered, it was simply impossible to steer clear of the "Woman Question" altogether, or to be untouched by its most fundamental demands.

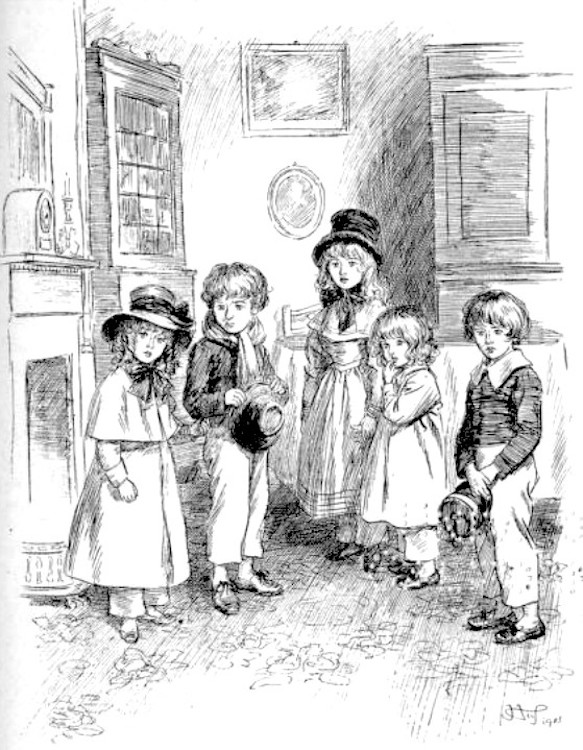

On her death-bed, Amos Barton's wife tells her eldest child Patty, "Love your papa. Comfort him; and take care of your little brothers and sisters. God will help you." She replies obediently, "Yes, mamma" (58). Illustration by Hugh Thomson from "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton," in Scenes of Clerical Life (Macmillan, 1906, facing p. 92).

Eliot, despite her sympathetic identification with Maggie Tulliver in The Mill on the Floss, has not always found favour with feminist critics, and is still looked at somewhat suspiciously by them. How could a woman who outraged her contemporaries in her private life so often seem to recommend self-sacrifice to other women? But "seem" is probably the operative word. For instance, the ending of "Amos Barton," in which Patty Barton is shown obediently taking her dead mother's place by her father's side, while the rest of the Barton children are forging on in life, is apt to be criticized; but, as Barbara Hardy has noted (15), this is because some clues have been missed. Patty's situation is not presented as an ideal one. Far from it. She is first seen at nine years old, a serious girl "whose sweet fair face is already rather grave sometimes" (19). At this stage, she tries to spare her mother as much as she can, cares for her siblings, and helps her mother cover books for her Evangelical father to present to the library. Since the Bartons' sitting room is also their day nursery and schoolroom, she can be having little education. In other words, like so many eldest daughters in a large family, with a mother frequently indisposed by pregnancy, she is being brought up to be no more and no less than her mother's right hand. When this mother (one of those domestic paragons, besides) asks Patty on her death-bed to love and comfort her father, and care for the smaller children, there is no hint of blame for the gentle, self-effacing mother, nor any question of Patty's pursuing a life of her own choosing. But her prematurely anxious face speaks volumes. Eliot went on to focus much more closely on the plight of the circumscribed girl in her full-length works.

However, no one dealt better with the problems of thwarted female potentiality than Charlotte Yonge, and nowhere did she do so better than in The Daisy Chain. Ethel, as noted earlier, is one of those clumsy and difficult girls like Maggie Tulliver who have special problems in adapting themselves to the feminine role, and who make immense claims on our sympathy. She has a governess who holds her back from the intellectual challenges she yearns for, and insists instead on the tidiness she scorns. The whole weight of family and Christian ethics is produced to quash Ethel's ambition, though it is quite clear that, given the time and encouragement that the boy gets, she could more than keep pace with her scholastically-gifted elder brother Norman. But it is Norman himself who says, "I assure you, Ethel, it is really time for you to stop, or you would get into a regular learned lady, and be good for nothing." Thus, while Norman goes on to win academic laurels, she must allow herself to drop behind, to concentrate instead on being a good daughter and sister. Even her project for building a church and opening a schoolhouse in nearby Cocksmoor must not be allowed to "swallow up all the little common lady-like things" (181-82). Ethel's reward for selflessness, in these matters and in giving up her chance of a particularly eligible match, is to displace her invalid elder sister as her father's companion.

Yonge, like Eliot in The Mill on the Floss, seems to have put her own deepest yearnings into her heroine; but here the author faces the facts squarely, and makes sure that her readers face them too. Ethel knows the limits of her reward: she foresees a lonely old age after her father has died and her younger siblings have have grown up. As far as this world is concerned, it is clear that nothing can quite compensate for the checking of personal aspiration. While Yonge's avowed purpose is to check it, she by no means glosses over the pain involved. As for the consolation of heaven (the "Final Rescue" which Eliot offers Maggie Tulliver), it seems a distant one.

Related Material

- 1. Introduction and "Plain Janes"

- 2. The Mantle of Domesticity

- 3. Difficult Passages

- 5. Finding an Occupation

- 6. The Next Step, and Conclusion

Bibliography

Brontë, Charlotte. Jane Eyre. Ed. Q. D. Leavis. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966.

Eliot, George. The Mill on the Floss. Ed. A. S. Byatt. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

_____. "The Sad Fortunes of the Reverend Amos Barton." In Scenes of Clerical Life. Oxford (World's Classics series) : Oxford University Press. 3-64.

England's Daughters: What is Their Real Work? (anonymous pamphlet). London: G. J. Palmer, 1870.

Hardy, Barbara. George Eliot: A Critic's Biography. London: Continuum, 2006.

Meredith, George. The Egoist: A Comedy in Narrative. New York: Scribner's, 1910.

Schreiner, Olive. The Story of an African Farm. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971.

Yonge, Charlotte. The Daisy Chain or Aspirations: A Family Chronicle. London: Virago, 1988.

Created 8 July 2018