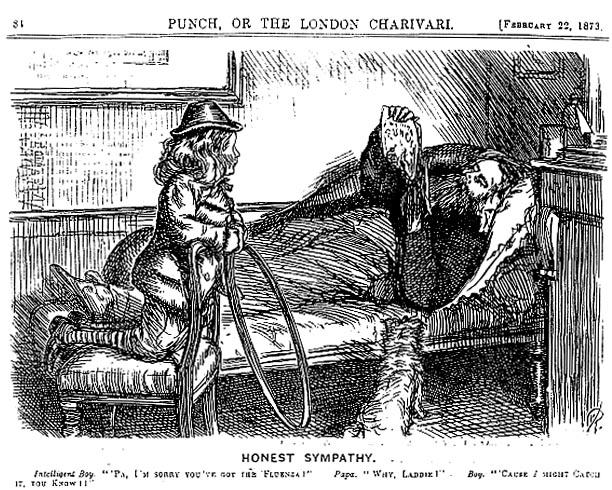

hild mortality was decreasing by the end of the century, as a result of improved working and living conditions, public health measures such as vaccination, and better medical treatment. For instance, the mean annual death rate (per million living) for male children between the ages of one and four had roughly halved, declining from over 36,000 in the period 1848-72, to about just under 19,000 between 1901 and 1910; for older children, the change was still more dramatic (see W.D. Logan, Tables 4A and 5A). A Punch cartoon published soon after the end of the first period (in the issue of 22 February 1873) could already afford to take the subject of childhood influenza lightly [....]. Concern with children's premature decease began to seem morbid.

HONEST SYMPATHY: Intelligent Boy: Pa, I'm sorry you've got the 'fluenza!" "Why, Laddie?" "'Cause I might catch it, you know!!"

Two trends of thinking supported this view, the one Christian, the other post-Darwinian. Kingsley and the writers associated with his muscular brand of Christianity celebrated the fighting spirit. Hughes's frail Arthur must be toughened up by Tom Brown, so that he becomes strong enough to survive the fever, to do the good work on this side of the river, alongside his great headmaster, Tom himself, and many of their fellows. For others, however, Christianity had lost its power either to inspire or to console. The traditional formulae for dealing with bereavement were being lost. What Trollope's hard-hearted Sir Hugh says to his poor wife in The Claverings, when she murmurs her pious submission to God's will and hopes for their only son's reception into heaven, must have looked more like common sense than callousness to some readers: "That's all very well in its way," said he, "but what's the special use of it now? I hate twaddle" (209). This was in the late '60s. Nearly three decades later, when Jude's son 'Old Father Time' takes the lives of Sue and Jude's babies in Jude the Obscure, and then commits suicide himself, the doctor, "an advanced man," can offer "no consolation" to the shattered parent (287). If this was the new way of treating child death, perhaps (as the reception of the novel also suggested), it was better not to deal with it at all. "Commonly," wrote W.D. Howells in Harper's Weekly, "a boy like the son of Jude ... hardens himself against his misery, fights for the standing denied him, and achieves it" (255). Nothing could be more indicative of what was now generally expected from a child character in fiction.

In fact, children do still die in novels occasionally: in 1894, Mrs Ward has a bronchitic little boy expire in front of the philanthropic heroine in Marcella, very much in the style of the early Dickens; but such cases are now rare. Indeed, Ward's best-known child character is Sandy in David Grieve, whose impish doings were modelled on those of her nephew, Julian Huxley. The child death-bed scene, like photographs and paintings of sleeping, dying or dead children, no longer seemed relevant. But the novelists had not written in vain. For example, the cruelty which brings Tom to the water's edge in The Water-Babies pricked the general conscience so painfully that the Chimney Sweepers' Regulation Act, which prohibited the employment of children for this purpose, went through within the year (though three Chimney Sweeps' Bills introduced into Parliament in the previous decade had all been defeated, despite the presentation of irrefutable evidence of the barbarism involved). Moreover, at a time of large-scale loss, the novelists had consoled the inconsolable with the companionship of shared tears. As George Eliot says at the end of "Amos Barton," "No outward solace could counteract the bitterness of this inward woe. But outward solace came" ([....] 111). Sick children themselves apparently did draw encouragement from such sources, and were capable of valiant efforts of faith. The Earl of Shaftesbury was deeply impressed by the serene acceptance achieved by one of his sons who died of pleurisy at Harrow, at the age of sixteen (see Battiscombe 208). As for the modern reader, the novelistic skills with which some Victorians explored the last critical days and even moments of a child character's life still invite admiration.

Created 24 July 2007

Last modified 22 February 2025