In 1865, Lewis Carroll published his book Alice in Wonderland; the Crimean War promptly was labelled Britain in Blunderland. From the publicity given at the time, particularly in The Times, the epithet is understandable.

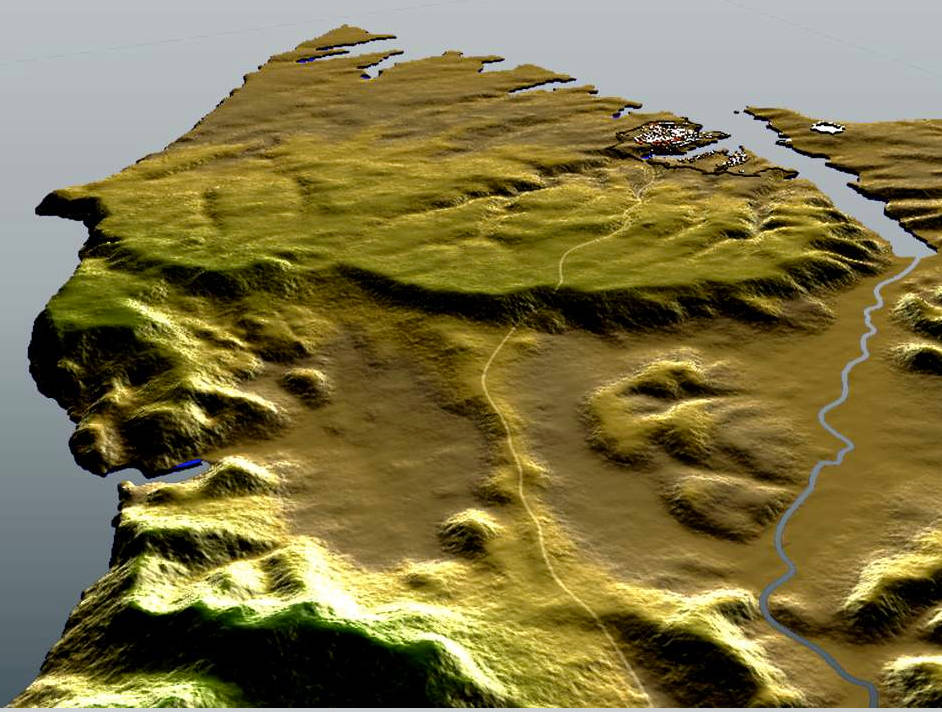

Two of Hugh Small's three-dimensional maps of the geography of the Crimean War. Left: Overhead view of Sebastopol and Todleben’s earth fortifications – the closed redoubt is the Malakoff, the open one is the Redan . Right: A view of the Chersonese. To the right of the road is the North Valley, where the Charge of the Light Brigade took place. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The British forces were led by Lord Raglan, aged 66 and who died in the Crimea. In 1810, the Duke of Wellington chose Raglan to be his Military Secretary, having driven Colonel Bathurst to a nervous breakdown. Raglan always preserved his serenity, no matter what was going on around him. He was also tactful, industrious and discreet. Because Raglan had served under and admired Wellington, he tried to follow the Duke's methods without having the same abilities. Perhaps worse, at times he thought that the French were still the enemy. Raglan often was mistaken for Wellington's son because they had the same blue eyes, the same beaked nose and healthy complexion. They were always friends. Unlike many of the officers who were in command during the Crimean War, Raglan had actually seen active service, having fought in the Peninsular Wars. There, he proved his bravery and also his complete indifference to danger: it could be said that either he was a very brave man or extremely foolish.

The French forces were led by Marshall St. Arnaud, who died in the war and was replaced by Canrobert. However, there was no overall supreme command and there was a lack of co-operation between the two armies; also there was conflict between the leaders and Raglan tended to allow the French commanders to direct the campaign.

The British army

30,000 British soldiers were sent to Turkey: this was fewer soldiers than the French sent. It comprised

- 10 brigades of infantry (each of 3 regiments). 2 brigades formed a division

- 2 brigades of cavalry and complementary numbers of engineers and artillery.

Finding enough soldiers to send to the Crimea was difficult; finding sufficient capable and adequately experienced officers to command the five infantry divisions was an even greater problem. Only two of the officers chosen had experience of commanding in action anything larger than a battalion; only one of them was under 60 years old, and he had never been in action before: he was the 35-year-old Duke of Cambridge, a cousin of Queen Victoria and the Commnder-in-Chief of the Army. He took 17 carts full of luggage with him to the Crimea. Another major problem was in the way that the army was organised. Seven more-or-less independent authorities shared in the organisation of the army, resulting in complications, muddles, duplications of work, jealousies and labyrinthine processes of supply and control.

The War: a brief outline

Map of the Turkish Empire in 1854: the map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's book, The Destruction of Lord Raglan (Longmans, 1961), p. 10, with the kind permission of the author. Alvin Wee of the University Scholar's Programme created the electronic version. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image

The original aim of the campaign was to force the Russians to leave the Turkish territories of Moldavia and Wallachia so initially the army landed at Gallipoli where 'a soldier could get drunk for 6d and syphilis for 1/-' [Hibbert]. The whole of May 1854 was spent in the town, which was dirty, overcrowded and expensive. In June 1854 the war aims changed because the Russians had left Moldavia and Wallachia. It was decided to take the army to the Crimea in order to destroy Sevastopol and the Russian fleet. The Duke of Newcastle, who was Secretary for War in Aberdeen's government, read out the order authorising the army to go to the Crimea to a half-asleep Cabinet, which approved of a document they had hardly heard.

The army was then put on board transport ships to take them through the Straits, past the forts that guarded the entrance to Constantinople and so on to the Black Sea town of Varna, which Omar Pasha told the allies was a 'very healthy spot'. The troops quickly fell prey to cholera. The London press reported that the Allies were to be sent to the Crimea before the armies left Varna. The Czar knew exactly what the Allies were doing, therefore — and often before the Allied commanders did. As Czar Nicholas said, "We have no need of spies; we have The Times". Because conditions were so appalling and the losses were so great at Varna, the British troops were moved 8 miles inland to Alladyn, where cholera and diarrhoea continued to take their toll. It was decided to allow the troops to wear beards, to save them from cutting themselves to pieces while attempting to shave.

On 18 June 1854, the Duke of Cambridge invited Canrobert to review the Guards Brigade. The Guards flew their battle-honours, and Canrobert found himself saluting the flags which carried the names of great English victories — mainly the most disastrous campaigns for the French — on the Anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo. Thereafter, Anglo-French relations became somewhat strained. On 10 August 1854 a fire at Varna destroyed thousands of pounds-worth of stores, including 16,000 pairs of boots and over 150 tons of biscuits. It was believed that the fire was started by the Greeks.

By this time, the British army had been reduced to 27,000 effective men, the French army to 30,000 effective men; the Turks could field 7,000 effective men. The allied army knew virtually nothing about the strength of Sevastopol or of the numbers of Russian soldiers in the Crimea. The British Foreign Office thought that Russia had a total of one million in armed forces, of whom 45,000 were in the Crimea, including 17,000 sailors; St. Arnaud thought there were about 70,000 Russians in the Crimea. Raglan did not express an opinion.

Map of the west coast of the Crimea: the map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's book, The Destruction of Lord Raglan (Longmans, 1961), p. 10, with the kind permission of the author. Alvin Wee of the University Scholar's Programme created the electronic version. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image

The Allies then left Varna for the Crimea: their chosen landing place was Eupatoria, about a hundred miles from Sevastopol, which was the main Crimean town. The march could have been completed within a week of their arrival. At this point, the generals showed themselves to be a match for the politicians in incompetence. On 13 September 1854 the transports arrived off Eupatoria. The following day the Allies began to land. The French landed first and within an hour several French Regiments were on shore; they had advanced posts as much as four miles inland. By noon, an entire division was established in a defensive position. The British landing was 'something of a muddle' [Hibbert].

Each infantryman carried a rifle with a fixed bayonet, 50 rounds of ammunition, a blanket and greatcoat, an extra pair of boots, socks and shirt plus a forage cap, a canteen of water, part of his unit's cooking equipment, three days rations comprising 4½ lbs meat and 4½ lbs biscuit. There was no means of moving the supplies because Raglan had been provided with no land transport and he had to collect oxen, horses and carts from the local people. It proved to be impossible to move the sacks of biscuits, barrels of salt meat, boxes of ammunition and other equipment. The tents had to be reloaded onto the ships because they could not be carried because of inadequate transport. The tents used in the Crimea had been made for the Peninsular army in 1811-12, were full of holes and were not waterproof. Then it began to rain and carried on raining, so the soldiers could not make any fires to cook their meals.

General Airey, aged 51, had by now taken over as Quartermaster-General because Lord de Ros was ill and had gone back to England. Airey foraged for transport with some success: he managed to find 350 wagons with teams and drivers, plus 67 camels, 253 horses and some supplies of food. Even so, the British had to abandon equipment and supplies which they were unable to carry with them, including 6 chests of tea. The French had a much better transport system.

The march from Eupatoria began: the French claimed the side of precedence on the right flank and so were between the British troops and the sea, and thus were largely protected from attack. The British soldiers were exposed on three sides in an unknown country without out-patrols and were marching in a dangerously compact mass. This shows the inexperience of the generals. Water was short and troops began to abandon their equipment and various items of their uniforms on the march because of the day-time heat. Unfortunately, the temperatures dropped rapidly at night, leaving men cold and wet, without shelter and without their greatcoats.

Soldiers of the 93rd Highland Regiment. With the 42nd and 79th regiments they formed the Highland Brigade under Sir Colin Campbell. Click on the thumbnail for a larger image.

Lords Lucan and Cardigan had already begun to argue and fall out which led to dissension among the officers. To add to the difficulties, Raglan rarely issued orders: he was very polite and imprecise. He advised his officers and left the decision in their own hands. Sir Colin Campbell, who commanded the Highland Brigade, had served under Moore and Wellington and had fought all over the world — Spain, America, China. He was brave, talented, and highly respected by his men, but since he had neither money nor influence after 44 years of distinguished service, he remained a colonel. Sir George Brown, who commanded the Light Division, was the most unpopular infantry officer in the army — a bully who believed in flogging. He was very short-sighted (as were most of the high-ranking officers — it seems almost a pre-requisite for the job), but disdained the use of spectacles and never listened to anyone.

Last modified 10 May 2002