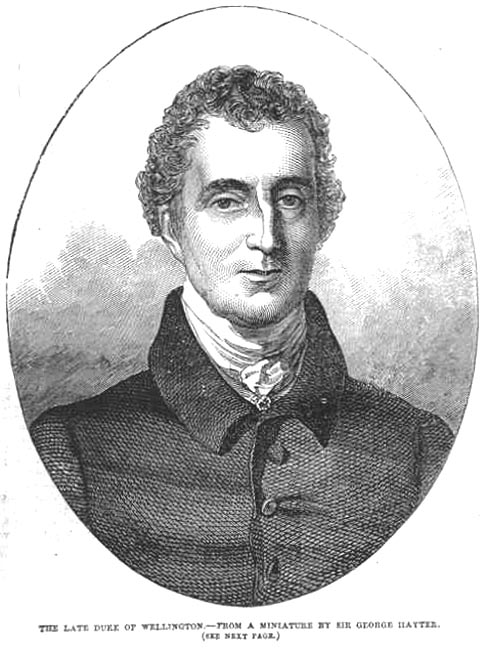

Three paintings of the Duke reproduced in The Illustrated News (1852) — left to right: Portraits by Pelligrini, Sir Thomas Lawrence, and Sir George Hayter. [Clock on thumbnails for larger images.]

Arthur Wellesley, the first Duke of Wellington and one of England's greatest military leaders, served as Prime Minister from 22 January 1828 to 16 November 1830 and again from 17 November to 9 December 1834. The third son (the fourth child of six) born to Garrett Wesley, first Earl of Mornington and Anne Hill, the man later known as "the Iron Duke" was born in Dublin on 1 May 1769. The family was from the Anglo-Irish ascendancy and Wellington maintained links with his Irish family and friends throughout his life. He was educated at the Diocesan School at Trim in County Meath; between 1781 and 1784 he attended Eton and then was tutored privately by the Rev. Henry Michell in Brighton. In 1785 he went to Brussels where he was again tutored privately. He had little interest in education and appeared to be uncomfortable with society life.

In order to find something which "poor Arthur" could do, his parents purchased a commission as an ensign for him in the 73rd Regiment of Foot in May 1787; in December he became a Lieutenant in the 76th Foot and the following month he transferred to the 41st in Dublin. Later he moved to the 12th Light Dragoons. When he arrived in Dublin, he became aide-de-camp to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland and served in that post until March 1793.

On 30 April 1790 Wellington was elected to the Irish parliament in Dublin as MP for Trim even though he was under age at the time. He continued to represent the constituency until 1797 when he left to go to India. He also continued in the army, moving up in rank through the purchase system:

30 June 1791 Captain in the 58th Foot

30 April 1793 Major in the 33rd Foot

September 1793 Lieutenant-Colonel

May 1796 Colonel

Wellington saw active service for the first time between June 1794 and April 1795 when his regiment was posted to the Netherlands in the early stages of the French Wars. His next experience of warfare was in India during the fourth Mysore War where he was involved in the fighting against Tippoo Sultan. The campaign culminated in the siege and fall of Seringapatam in May 1799; Wellington was appointed as Governor of Seringapatam by the Governor-General of India, Lord Mornington — who happened to be Wellington's eldest brother.

In 1803, and by then a Major-General, Wellington fought in the second Mahratta War against Scindiah of Gwalior; his successful campaigns included victories at Assaye and Argaum. Wellington was created a Knight of the Bath for his work in India in September 1804. He returned to England a year later and reported to Lord Castlereagh at the Foreign Office. There he met Admiral Lord Nelson who died six weeks later, on 21 October, at the Battle of Trafalgar. Wellington was appointed Colonel of the 33rd Regiment of Foot in January 1806.

April 1806 was a busy month for Arthur Wellesley: he was elected as MP for the borough of Rye on 1 April; on 10th he married Catherine Pakenham in Dublin. She was the daughter of Baron Longford, also one of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. In 1791, Wellington was in debt and Lord Longford refused to allow him to marry Kitty; it seems that Wellington felt obliged to keep his promise to marry her even though he found her very trying. Kitty was over-emotional, self-critical, and easily depressed. She was incompetent as a housekeeper and continually found herself in debt, which infuriated Wellington, whom she hero-worshipped. She was described by contemporaries as unaffected and simple-minded. Kitty died on 24 April 1831, but the couple had been estranged for a long time prior to that. On 22 April Wellington made his maiden speech in the House of Commons, defending his brother's Indian policies. In 1807 Wellington found himself elected as MP for Mitchell in Cornwall, Newport on the Isle of Wight and for Tralee in County Kerry. He chose Newport. Concurrently he was appointed as Chief Secretary for Ireland by the Duke of Portland and worked with Charles Lennox, Duke of Richmond who was the Lord-Lieutenant. Like Wellington, Richmond served in the British army from 1787.

By October 1807 the Peninsular Campaign was under way after the French declared war on Portugal, Britain's oldest trading partner. The French occupied Spain in May 1808, which led to a Spanish and Portuguese revolt. A British expeditionary force under the temporary command of Wellington was sent to Iberia on 1 August by Lord Grenville's ministry; in its first campaign the British defeated the French at the Battle of Rolica and at Vimeiro. Unfortunately, the new commander, Lieutenant General Sir Henry Burrard insisted that the Convention of Cintra was signed: it gave very favourable terms to the French. Wellington was blamed for the Convention although he was cleared of responsibility by a military enquiry in Britain whence he returned in October 1808. Sir John Moore was left in command of the army in the Peninsular. In January 1809, Moore led his troops in retreat to Corunna but was killed in the subsequent battle. Wellington resigned as Chief Secretary for Ireland and resumed command of the army in Iberia. From then until 1815, Wellington was occupied with leading the British army in the defeat of the French.

He was created Earl of Wellington in February 1812 at Spencer Perceval's recommendation; eight months later, at the start of Lord Liverpool's ministry, he was elevated to a Marquisate and in May 1814 he was given a Dukedom; he took his seat in the House of Lords in June. Parliament gave him several grants of money in recognition of his achievements in the French Wars including a £15,000 annuity in 1814 and £200,000 in 1815 to buy an estate: he purchased Stratfield Saye in Hampshire.. He also received £60,000 in prize money after the Battle of Waterloo but returned £40,000 of this to the Treasury.

The Duke of Wellington bought Stratfield Saye in 1817, using the money voted to him by parliament for 'services rendered' in the defeat of Napoleon.

Wellington's comment after the Battle of Waterloo was, 'Nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won'. Although he was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, he did not return to active military life but became a politician and 'elder statesman'. He was important as a diplomat in the years following the defeat of Napoleon at the Battle of Leipzig in 1814 and then after Waterloo in June 1815:

August 1814 Wellington took up residence in Paris as Ambassador to France

April-March 1815 he was Britain's representative at the Congress of Vienna

July-November 1815 (after Waterloo) he was commander of the army of occupation in France; he was Britain's delegate to the Congress of Aix la Chapelle

October-November 1822 he was Britain's delegate to the Congress of Verona

February-May 1826 Wellington was sent to Russia to try to avert a Russo-Turkish war over Greece. Czar Nicholas I had succeeded to the throne in 1825 and was very much an 'unknown quantity' at this point

On 22 January 1827 Wellington accepted the post of Commander-in-Chief of the British army but resigned when Canning became PM in April. He was reappointed by Goderich in August 1827 and then became PM in his own right on 22 January 1828. When it was realised that he was still Commander-in-Chief there was a public outcry and he was forced to resign that position.

Wellington's Tory government was defeated in the House of Commons when MPs voted in favour of repealing the Test and Corporation Acts. In February 1828 Wellington decided to pass the legislation himself, a measure in diametric opposition to traditional Tory 'Crown, Church and Constitution' policies. The next month Wellington's President of the Board of Trade introduced legislation for a sliding scale on corn duties which was passed without amendment. Huskisson refused to vote with the government and resigned, precipitating the County Clare election that led ultimately to the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act on 13 April 1829. However, before the legislation passed, the Duke fought a duel with Lord Winchilsea over the issue of Catholic Emancipation: both men deloped and honour was deemed to be satisfied. Wellington also took the opportunity of Huskisson's resignation to remove all the other Canningites who were in his Cabinet.

"Number 1, London": Apsley House, the London home of the Duke of Wellington. Courtesy of English Heritage, Apsley House. The Duke had steel shutters fitted to the windows because they were cheaper than replacing the glass each time a mob broke them. [Click on thumbnail for larger image and more information.]

Following the death of George IV, the new king William IV kept Wellington as his PM; however, the campaign for parliamentary reform was gathering strength and was advocated by the Whigs in both Houses of Parliament. On 2 November, Earl Grey demanded to know whether Wellington intended to introduce any reform measure. Wellington's speech in response to Grey's question caused such a furore that he was obliged to resign on 16 November; Earl Grey formed the first Whig ministry since 1783 and brought in the so-called Great Reform Bill in 1832. After Grey's resignation in July 1834, a ministry that lasted only four months was formed by Lord Melbourne. When he resigned, the king asked Wellington to form a ministry. The Duke declined but suggested that the post should be offered to Sir Robert Peel who was in Italy. Wellington became acting PM until Peel's return, remaining in the Cabinet as Foreign Minister in Peel's first ministry. When Peel resigned in April 1835, Wellington found himself out of office; he led the Tory opposition in the House of Lords until the start of Peel's second ministry in September 1841, at which point he became a Cabinet Minister without Portfolio until Peel's next resignation in June 1846.

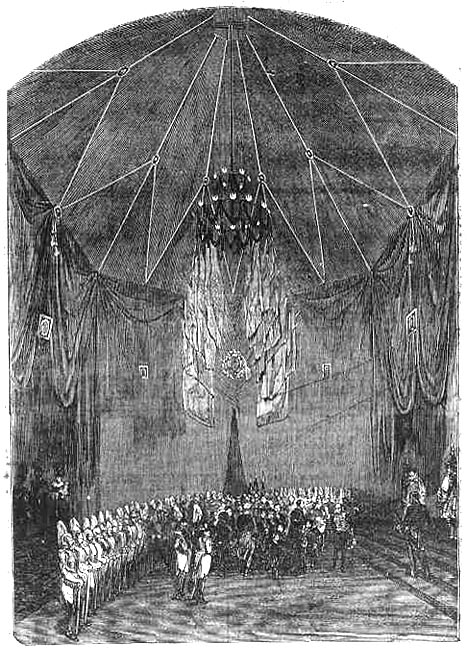

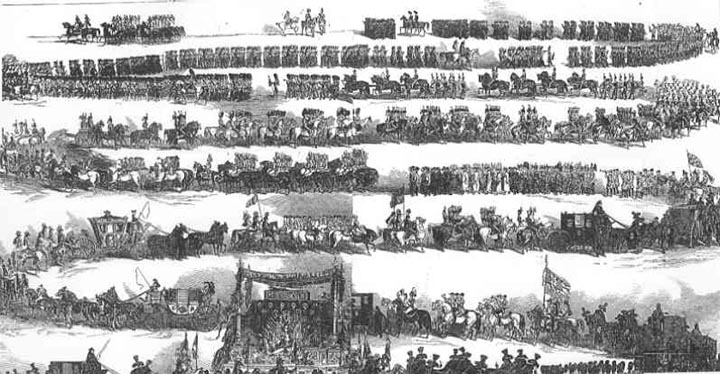

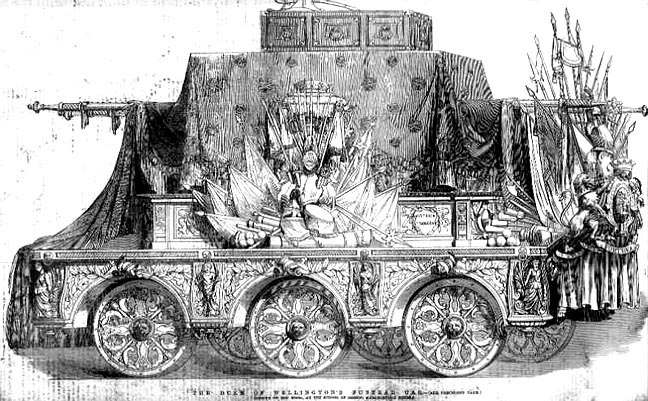

Three illustrations from The Illustrated London News's series on Wellington's funeral — left to right: Lying in State at Chelsea Hospital; the Funeral Procession; and The Duke of Wellington's Funeral Car. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Once he was out of office, Wellington was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of the army, a post that he held until his death, which took place suddenly at Walmer Castle on 14 September 1852. He lay in state there until 10 November and then in Chelsea Hospital until 17 November. He was given a state funeral and was buried in St. Paul's Cathedral. He was 83 years old.

Related Materials

- "Young Wellington in India" [Review of an exhibition at Apsley House]

- Wellington’s Speech on Catholic Emancipation (April 2, 1829)

- Wellington as pragmatic Tory politician

- Wellington at Waterloo

- Field-Marshall His Grace the Duke of Wellington by Sir Thomas Lawrence

- Monuments to the Duke of Wellington

- “Don't be a d––d fool, sir”

- A Review of Peter W. Sinnema's The Wake of Wellington

- Preparations in St. Paul's Cathedral for the Funeral of the Duke

- George Canning’s Response to the King's Speech in the House of Lords (2 November 1830)

- Sir Robert Peel on the repeal of the Corn Laws (28 May 1846)

- John Ruskin's Skeptical Appraisal of Wellington

- The Battle of Waterloo [outside the Victorian Web at www.napoleon-battles.com

Recommended reading

James, L. The Iron Duke: a military biography of Wellington. London, 1992.

Longford, E. The Years of the Sword. London, 1969.

Longford, E. Wellington: Pillar of State. London, 1972.

Muir, Percy. Wellington: The Path or Victory. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013.

Muir, Percy. Wellington: Waterloo and the Fortunes of Peace. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015.

Created 2000

Last modified 29 October 2018