illiam Strachan, born in Edinburgh in April 1715 and educated at the High School there, served an apprenticeship as a journeyman printer in the Scottish capital before taking “the high road to England,” where he was employed as a compositor for a London printer from May 1736 until February 1738. By November of that year, dropping the ‘c’ from his name to make it appear less Scottish, Strahan was in the printing business himself, with one press. In that first year he got work from eight clients, including printer, publisher and fellow-Scot Andrew Millar, his former employer, who became Strahan’s best customer, increasing his orders steadily every year until his death in 1768. Thus, after Millar became Fielding’s publisher, around 1742, Strahan began printing his works and by 1779 had printed almost 63,000 copies. He also printed over 20,000 copies of Thomson’s hugely successful Seasons for Millar and almost as many of Hume’s Essays and his popular History of England. By 1754 Strahan had nine presses going and was responsible for printing Johnson’s Dictionary for Millar. He likewise became the chief printer for Thomas Becket, a former apprentice of Millar’s, who had opened a publishing firm of his own (James Macpherson’s Fingal [1763], Sterne’s Sermons of Mr. Yorick [1760] as well as parts of Tristram Shandy [1760-67] and A Sentimental Journey [1768]).

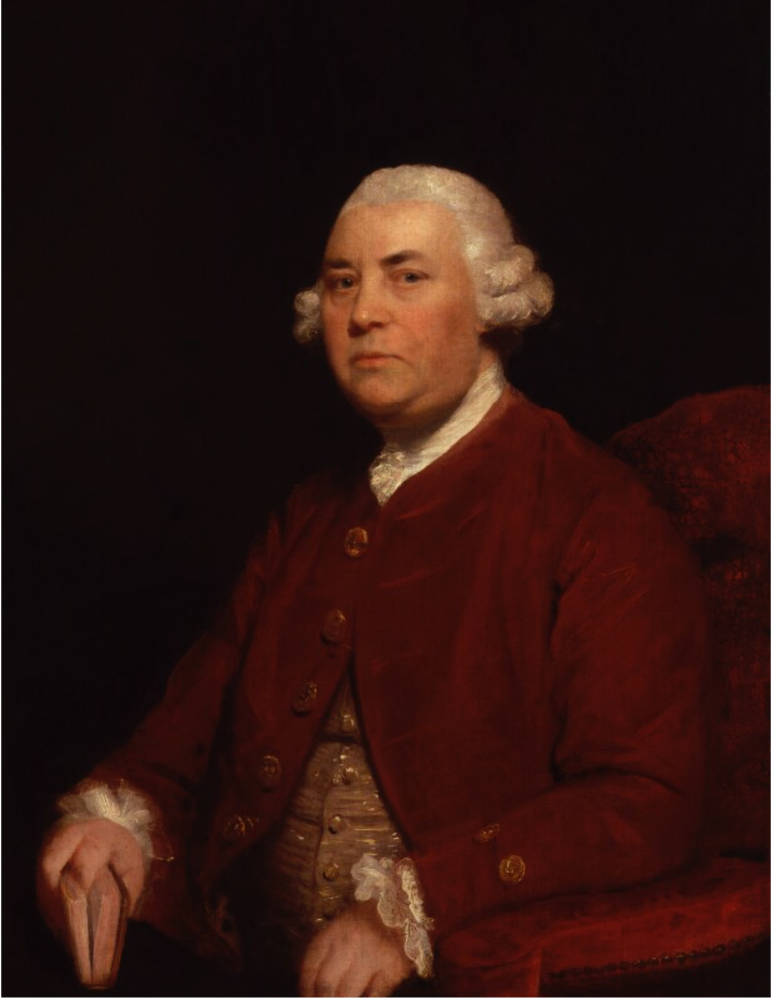

William Strahan by Sir Joshua Reynolds. 1780. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London. Click on image to enlarge it.

Strahan finally entered publishing himself by buying up more than forty of Millar’s titles after the latter’s death in 1768. These included the works of John Locke and Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). He also collaborated in many publishing ventures with Millar’s successor, Thomas Cadell, who became, in addition, the most important client of Strahan’s printing business. In 1771 Strahan took a half share in an Edinburgh publication of Fingal and in Henry Mackenzie’s popular novel The Man of Feeling, which went through eight editions by 1781 and sold many thousands of copies. 1775 saw the publication, again in collaboration with Millar’s successor Cadell, of Johnson’s A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland and 1776 that of the first volume of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (which had been turned down by other publishers and for which Strahan doubled the fee Cadell had offered the author) as well as of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations.

Strahan was a personal friend of many of the writers he published: Hume (who made him his literary executor in a codicil to his will in April 1776), Smith, Johnson, Gibbon, Mackenzie. One of his visitors from Scotland -- one Dr. Thomas Somerville, a minister in Jedburgh and subsequently the author of a History of Great Britain during the Reign of Queen Anne (1798) -- describes going to dinner at Strahan’s in 1769 and finding gathered there David Hume, the eminent physician John Pringle (soon to be appointed physician to George III), Benjamin Franklin, and Johnson’s friend Mrs. (Hester) Thrale. The relationship with Franklin was especially close. It was on Strahan’s recommendation that in 1743 Franklin brought Strahan’s young friend and former fellow-apprentice in Edinburgh, David (Davie) Hall, yet another Scot, to Philadelphia to serve as his assistant in his printing shop. Hall soon became a partner, taking over the day-to-day running of the shop early in 1748, and taking it over completely in 1766 when the partnership with Franklin was dissolved. Though severely tested at the time of the American War of Independence — Strahan, who had strong political interests and had won (or purchased) a seat in Parliament in 1774, understood the grievances of the American colonists, but strongly opposed their armed revolt and supported the British government’s attempts to put it down — the friendship of the two men survived and was renewed after the end of the war.

Strahan’s portrait was painted by Reynolds — an indication of the eminent place the printer-publisher occupied in the culture of his time. It was first exhibited in 1783, shortly before Strahan died and is now part of the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London.

On Strahan’s death in 1785, the business was carried on by the youngest of his three sons, and on the death in 1831 of Andrew Strahan, who had no children of his own, by Andrew’s nephew by marriage, Andrew Spottiswoode, the scion of an old Scottish family. The firm then tended, however, to concentrate on printing -- government reports, scientific, political and economic writings, and, on commission from the publishers, some literary works (by Robert Browning, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Fenimore Cooper, among others).

Spreading the Word: Scottish Publishers and English Literature 1750-1900

- Scotland and the Modern World: Literacy and Libraries

- Scottish Publishers, London Booksellers, and Copyright Law

- Andrew Millar (London) 1728

- William Strahan (London) 1738

- Robert and Andrew Foulis, The Foulis Press (Glasgow) 1741

- John Murray (London) 1768

- Bell & Bradfute (Edinburgh) 1778

- Archibald Constable (Edinburgh) 1798

- Thomas Nelson and Sons (Edinburgh) 1798

- John Ballantyne (Edinburgh) 1808

- William Blackwood (Edinburgh) 1810

- Smith, Elder & Co. (London) 1816

- William Collins (Glasgow) 1819

- Blackie and Son (Glasgow) 1831

- W.& R. Chambers (Edinburgh) 1832

- Macmillan (Cambridge and London) 1843

- Lesser Publishers

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-century British Copyright Law: A Bibliography

Bibliography

Cochrane, J. A. Dr Johnson’s Printer: The Life of William Strahan. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964.

Last modified 31 October 2018