Two things need to be made clear at the outset: no one in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries spoke about 'folk tunes'; they talked, instead, of old airs and minstrelsy, and the main interest was in Celtic airs, particularly those of the two countries in which major rebellions had been recently suppressed. Scotland is the first to make an impact on the English with its 'national airs'. The reason could be traced back to the homesick Scots at the Anglo-Scots court produced by the Union of Crowns in 1603. The Scottish songs which directly helped to shape nineteenth-century bourgeois taste were, however, of more recent date, being associated with the name of Robbie Burns.

Interest in Scotland had increased in the eighteenth century following the Act of Union, 1707; until then England and Scotland had one ruler but were two states with two governments. It has already been pointed outthat Gay selected tunes from the first published collection of Scottish songs, William Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius of 1725. One of the attractions of this collection was Thomson's claim that seven of the airs were composed by Queen Mary Stuart's Italian secretary, David Rizzio. James Oswald went so far as to include airs of his own in The Caledonian Pocket Companion, stating that they were also by Rizzio. There is, in fact, no evidence to suggest that Rizzio ever composed anything. The fifteen small volumes of Oswald's publication appeared 1745—65 and were aimed to satisfy not [22/23] just the market for songs but also the demand for music suited to the fashionable flute.

Allan Ramsay (previously mentioned in connection with his ballad opera, The Gentle Shepherd) felt the need to preserve Scottish culture. His Tea-Table Miscellany (1723) contains words to Scottish airs which are named but not notated. Ramsay's preservation process involved the words in a great deal of literary improvement and moral purification, an exercise which was to become standard practice. Thomson took, without consent, thirty-eight of Ramsay's songs for his Orpheus Caledonius. As Burns did later, Ramsay portrays a peasant Scotland: his popular song 'The Yellow-Hair'd Laddie', depicting a love-sick girl milking her ewes, was something an urban society found quaint and appealing. It was Ramsay's 'Auld Lang Syne' which was later added to by Burns (although Burns did not expect the words to be put to Shield's tune).

Interest in Scotland was given a boost by James Macpherson's alleged translations of ancient Gaelic poetry transmitted to him orally. The verse was supposed to be the work of Ossian, a third-century bard. The collected works appeared in 1765. By reading Macpherson, Thomas Percy was stimulated to collect his unreliable and 'improved' Reliques of Ancient Poetry. Dr. Johnson, who never once credited the myth of Ossian, excited further interest in Scotland when he embarked upon his Hebridean tour in 1773.

Set against the fascination with Scottish culture is the fact that after the 1745 rebellion the Act of Proscription was passed, forbidding any wearing of Highland dress under threat of imprisonment without bail for six months (for a first offence) or transportation for seven years (for a second offence). This did not simply demand a change of fashion but a change of wardrobe necessitating a complete alteration of the weavers' looms which were set up for the weaving of the traditional sets. In some areas the poor were reduced to wearing sack cloth. The implied proscription of the piob mhor, the Highland war-pipe, may have done incalculable damage to ceol mor, the most unique and highly developed form of Celtic music. Those pipers who turned to the fiddle are responsible for today's distinctive West of Scotland fiddle style. There was no interest, either, in the living culture of Gaelic laments such as 'The Lament for William Chisholm', composed by his widow after his death at Culloden.

Another song undoubtedly inspired by Culloden was Jean Elliot's 'The Flowers of the Forest'. However, the words (set to an old air first notated in the Skene MS, c. 1615) are ostensibly about the battle of Flodden Field in 1513 when, in two hours of fighting, ten thousand Scots were killed and James IV was hacked to pieces. Maurice Disher claims that 'The Flowers of the Forest' was 'so deeply felt as to solemnize national mourning still' (22) and scorns the later version by Alicia Rutherford (Mrs Cockburn). He seems unaware that the pipe lament played at Scottish funerals to this day is, in fact, based on the 'improved' version of the tune by this middle-class Edinburgh lady.

By the time Pitt was recruiting from the Highlands for the conquest of Canada (1759), a ban on tartan could be lifted and songs could be permitted which celebrated Jacobite victories. Johnnie Cope' by Adam Skirven, which first appeared in a volume of Oswald's Companion, mocks the general who fled at the [23/24] battle of Prestonpans, 1745. Many have no doubt assumed that the use ot this tune for reveille by the present-day Scots Guards is designed to exasperate the English with a reminder of their defeat. Ironically, Sir John Cope was serving in that regiment 1710-12 before it was brought south to London by Queen Anne (to remain out of Scotland for two hundred years).

Relations with Scotland were further healed by the restoration of many forfeited estates in 1784. It was three years later that James Johnson began publishing The Scots Musical Museum which ran to six volumes. This work provided the cultural moment for an aesthetic reappraisal of Scottish songs: from now on the emphasis would not be on contrasting the artistic pretension of the Italian operatic aria with the simple 'folk' air, but on annexing the latter to the realm of high art. The key figure involved with the collection was the poet Robert Burns (1759-96), and the significance of this moment in Scottish culture was retrospectively acknowledged by the adoption of Burns' 'Scots Wha Hae' as the Scottish national anthem. He had published only a single volume of verse when he began contributing to the Museum. Burns was heavily involved in volumes 2 to 5 and did not hesitate to 'improve', add to, and rewrite any songs he found. He also contributed to George Thomson's Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs (the first volume of six being published in 1793). Although Burns had failed to rise in rank in his regular employment as an excise officer because of his republican sympathies, he consistently refused payment for his songs until nine days before his death when he requested help with the payment of a haberdasher's bill. A sense of the cultural importance of compiling a museum of Scottish song and preserving the Lallans dialect was sufficient motivation.

Johnson's Museum had presented the songs in the simplest of musical arrange- ments (a bass part with figured directions for harmony) by Stephen Clarke. George Thomson was more ambitious. As a cultivated member of the tasteful Edinburgh Musical Society and a clerical officer with the Board of Trustees for the Encouragement of Art and Manufactures in Scotland, he hit upon the idea of publishing Scottish airs in arrangements by Europe's leading composers.

Indicating the general change taking place in aesthetic attitude, the publisher William Napier had the identical idea at the very same time. The two great rivals in London in 1791 were Haydn and Pleyel, so it is no surprise to find Napier engaging the former and Thomson the latter. Ignace Pleyel's cello and piano accompaniments were too elaborate for the amateur market Thomson had in mind, so he changed to Leopold Kozeluch for his second volume. Kozeluch's arrangements did nothing to boost sales so he switched to Haydn. Haydn was then seduced away by another publisher, William Whyte, who offered to double Thomson's rate of one guinea per song if he would provide arrangements for his own two-volume Collection of Scottish Airs (1804—7). Haydn was apologetic; he was suffering financially from the effects of inflation which was crippling Vienna as a result of the war. Thomson seemed doomed to make little money on his project, yet he still insisted on the best-quality paper and binding and, as he saw it, the best-quality arrangements. He was not a professional publisher in the mould of Napier and Whyte; his motivation, like that of Burns, was patriotic sentiment. Thomson's dream was to produce 'a work that will ever remain the standard of Scotish [sic] Music' (quoted Fiske 67).

The publisher William Power saw a potential market for Irish songs 'improved' in a similar manner. The United Irishmen's revolt had been suppressed and the Act of Union in 1800 had prompted a drift of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy towards London. Power approached Tom Moore (1770—1852) who in 1807 had fallen out of favour with his patron, the Prince of Wales. Moore had already achieved acclaim for his drinking songs and the opera The Gipsey Prince (music by Michael Kelly, 1801). The products of this encounter, the Irish Melodies, were to prove a veritable corner-stone of bourgeois 'popular song' and provide Moore with a lucrative source of income, since he negotiated terms which gave him one hundred guineas per song. Between 1808 and 1834 they were issued serially in ten volumes, plus supplement. As happened with Burns, the cultural significance of Moore was later endorsed by the adoption of one of his songs as a national anthem: 'Let Erin Remember' remained Ireland's anthem until separation in 1921. These anthems illustrate classic hegemonic compromise: some acknowledgement of autonomy is demanded by Scotland and Ireland, yet their independence is recognized only in the context of a romantic and shadowy past. Of more recent date, the Welsh national anthem, 'Hen Wlad fy Nhadau' ('Land of My Fathers'), conforms to the same pattern, and here the possession of an ancient independent language becomes a symbol of the country's relative autonomy.

One of Moore's main sources for Irish tunes was Edward Bunting's A General Collection of Ancient Irish Music, the first volume of which had appeared in 1796. Bunting, a prominent Belfast musician, was inspired to begin his collection by the Belfast Harp Festival of 1792. In spite of considerable financial inducements, only eleven players arrived (one being Welsh), a symptom of the decline of the bardic tradition which had followed the rise of the Anglo-Irish gentry. Bunting's collection contained distortions dictated by contemporary taste: there were new English words, piano accompaniments, and, of course, the use of a 'classical' musical notation which 'corrected' what in terms of its own grammatical system were regarded as barbarisms, while being able only to approximate (when it was not simply ignored) the richness of traditional melodic ornamentation.

Moore chose to use no Irish dialect, but sometimes a novel English metre resulted from his fitting words to a Gaelic melody:

At the mid-hour of night when stars are weeping, I fly

To the lone vale we lov'd, when life shone warm in thine eye.

In the example above, an old Irish metre is used, called ambrániocht (see Boydell 15). Not all the melodies Moore chose, however, were Irish in the first place: 'Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms' was written to a tune already familiar to the words 'My Lodging Is on the Cold Ground', and 'As Slow Our Ship' uses the tune 'Brighton Camp', already popular in the eighteenth century as 'The Girl I Left Behind Me'.

The main sources for the words of Moore's historical songs included established works such as Walker's Historical Memoirs of Irish Bards and Warner's History of Ireland, [25/26] as well as the most recent transactions of the Gaelic Society of Dublin. 'Avenging and Bright', the song written to the Gaelic air 'Cruchan na Feine', is drawn from a translation of Deidre by O'Flanagan, a leading researcher in the Gaelic Society. Some of Moore's metaphors are taken from ancient Irish poetry, for example, a 'chain of silence' or the 'sun-burst' of an unfurled banner. The Irish Melodies were in large part responsible for a new romantic view of Ireland and often contained nothing more than melancholy nostalgia (like 'The Meeting of the Waters'), occasionally not involving Ireland at all (like 'Love's Young Dream'). Nevertheless, nostalgia for the days of Ireland's liberty could leave a subversive quality just beneath the surface of some songs. Take the last lines of 'The Valley Lay Smiling Before Me', set, tactfully, in the remote period of Henry II:

But onward! the green banner rearing,

Go, flesh ev'ry sword to the hilt;

On our side is VIRTUE and ERIN,

On theirs is the SAXON and GUILT

The words could as easily apply to the raising of the green banner at the battle of Vinegar Hill, 1798. For similar reasons it is no surprise to find 'The Minstrel Boy' reappropriated as an Irish song of resistance. Moore left Ireland to study law in London in 1799 but had been a friend of Robert Emmet, who led the unsuccessful Dublin Rising of 1803. Emmet was executed after being captured on a visit to his girlfriend Sarah Curran, who reputedly died thereafter of a broken heart. Moore makes oblique reference to these events in 'She Is Far from the Land'.

Sir John Stevenson, the vicar-choral of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, provided the accompaniments to Moore's Irish Melodies. It was a shrewd decision to steer clear of the Viennese style which was so ill suited to the collections of Scottish airs. Stevenson's sympathies lay with the Italian style. This was not entirely inappropriate since Celtic music had been coming to terms with Italian music for many years. In Scotland, over three hundred years before, James IV had emulated the life-style of an Italian Renaissance prince. In Ireland the 'last of the bards', Turlough Carolan (1670-1738), showed the unmistakable influence of those Italian contemporaries whose music was heard in Dublin (Corelli, Vivaldi, Germiniani) in his own harp music. Stevenson was familiar with at least some of Carolan's music: he adapted Carolan's wide-ranging air 'The Fairy Queen' for four voices in order that Moore could set words to it. The task of fitting words to this melody is considerable and shows the extent of Moore's skill. Stevenson's accompaniments rarely favour strong rhythmic patterns ('The Minstrel Boy' is an exception); he prefers to write rippling harp-like figuration. The simple, unfussy quality, in which, perhaps, rhythmic languor plays a necessary role, earns the arrangements the epithet 'chaste' from a mid-Victorian editor, who goes on to say in respect of the words: 'Little need be said of the merits of the work, the sentiments and narrative of the songs being such as will ever recommend them to the universal praise and sympathies of mankind.'28 In further support of Moore's healthy universality of appeal, Holman Hunt depicts in The Awakening Conscience (1854) a fallen woman beginning to realize the error of her ways after hearing her lover play a few bars of 'Oft in the Stilly Night' (one of Moore's National Melodies).

W. Holman Hunt's The Awakening Conscience. (1853). Click on the image to enlarge it and obtain more information.

The most well-known of the Irish Melodies was 'The Last Rose of Summer'.29 The tune was taken from Alfred Milliken's The Groves of Blarney of the eighteenth century, in turn thought to be based on a seventeenth-century Irish harp tune. The Irish harp certainly could not have played 'The Last Rose of Summer' in its present melodic shape, since once tuned it was fixed in pitch and therefore unable to cope with the sharpened note in the phrase 'no rosebud is nigh'. The accompaniment throughout is harp-like, although the chords are spread from low note to high in classical manner rather than high to low in the old Irish manner. Stevenson writes an accompaniment in triplets (three notes performed in the time of two) even though there is nothing particular in the tune to justify this approach. The rhythmic effect of triplets was soon to become a common device employed to generate gentle musical tension, evoking a mood of sweet melancholy. The melody itself is decorated with notes which momentarily clash, then resolve on to the accompanying harmonies, as occurs at the word 'of' in 'Tis the last rose of summer'.

These dissonances also create the tension necessary for evocation of the desired mood. Sometimes the dissonance is crude and unconsidered, as on the final syllable of 'rosebud'.

[28/29] Three of the four musical phrases reach their highest point in their respective first bars and are then dominated by a falling motion; it is easy to hear them as emotional musical parallels to the drooping of the dead 'lovely companions' and the heaving of 'sigh for sigh'.

[28/29] Three of the four musical phrases reach their highest point in their respective first bars and are then dominated by a falling motion; it is easy to hear them as emotional musical parallels to the drooping of the dead 'lovely companions' and the heaving of 'sigh for sigh'.

'Tis the last rose of summer,

Left blooming alone;

All her lovely companions

Are faded and gone.

No flow'r other kindred,

No rosebud is nigh.

To reflect back her blushes,

Or give sigh for sigh.

I'll not leave thee, thou lone one,

To pine on the stem;

Since the lovely are sleeping,

Go, sleep thou with them;

Thus kindly I scatter

Thy leaves on the bed,

Where thy mates of the garden

Lie scentless and dead.

So soon may I follow,

When friendships decay,

And from love's shining circle

The gems drop away!

When true hearts lie wither'd,

And fond ones are flown,

Oh! who would inhabit

This bleak world alone?

Moore's verses are typical of his output in seeking to conjure up a sense of loss; there is usually no remedy offered beyond the melancholy pleasure of indulging the feeling for its own sake, but in the circumstances described above he advocates floral euthanasia. The imagined loss of love and friendship was a cosy emotion to wallow in while encircled by family intimacy in the drawing room; in fact, it could only reinforce the pleasure of family ties in the comfortable knowledge that one did not inhabit this bleak world alone. It thus promoted the important 'Victorian, values' of friendship and family.

While Moore was producing his Irish Melodies, George Thomson had managed to interest Beethoven in arranging airs. At first Beethoven arranged Irish songs because Thomson was temporarily out of stock of Scottish songs (even so, Beethoven's 25 Irish Songs of 1814 include such unlikely examples of Hibernian minstrelsy as 'The Massacre of Glencoe'). Thomson had also taken an interest in Welsh airs, publishing three volumes of A Select Collection of Original Welsh Airs between 1809 and 1817 (Beethoven furnished twenty-six arrangements for the last volume). Moore's success soon found an echo in Thomson's publications: five tunes arranged by Beethoven in 1816 had already been used by Moore. Thomson has the poet William Smyth provide words of no possible ambiguity for 'The Soldier' (his version of 'The Minstrel Boy'): it is full of a military bravado befitting the calls of 'honour', 'country', and 'duty' during the close of the Napoleonic war.

'Tis you, 'tis I, that may meet the ball;

And me it better pleases

In battle, brave, with the brave to fall,

Than to die of dull diseases.

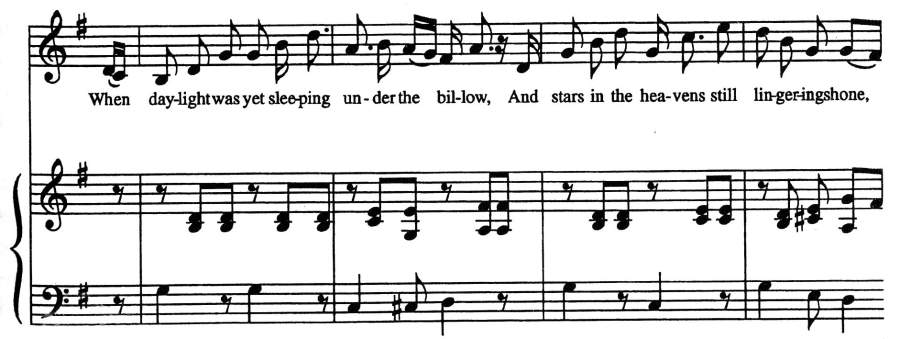

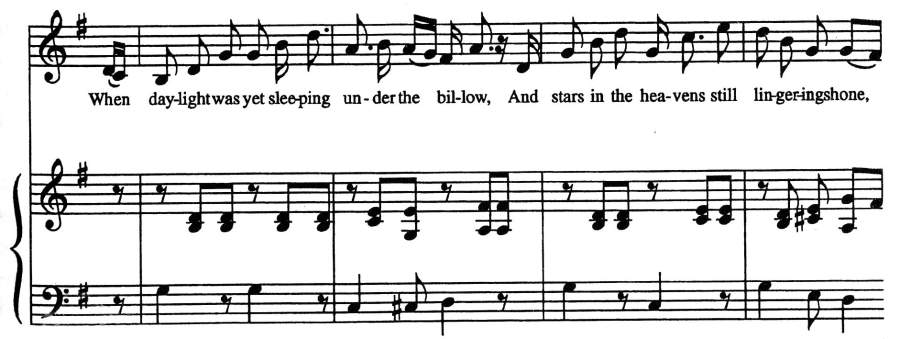

Thomson had several other poets working for him, including Sir Walter Scott, and also relied upon verses written by Burns. Beethoven, to his frustration, was often denied the text; Thomson feared that he would have the songs published on the continent and that they would then work their way from there into Britain. To Thomson's surprise, however, Beethoven's arrangements lacked the commercial success of Stevenson's. Thomson thought, in view of Beethoven's greater stature as a composer, that it was the comparative difficulty of his arrangements which was to blame. Beethoven responded tetchily to a reprimand on these lines, saying Thomson should have given him a better understanding of 'le goût de votre pays et le peu de facilité de vos executeurs' (your country's taste and your players' lack of expertise — Kalischer 140). A comparison between a Stevenson and a Beethoven arrangement of the same tune would indicate that the problem was not merely ease of execution. The song 'By the Side of the Shannon' (no. 8 of Beethoven's 12 Songs of Various Nationality) employs the same melody, 'Paddy's Resource', as that used for the alternative version of Moore's 'When Daylight Was Yet Sleeping'. Comparing nothing more than the melody's accompaniment, it is indeed evident that Beethoven demands more playing skill, but he also does two things which Stevenson does not: he duplicates the melody on the piano, and he provides musical punctuations within the phrase structure of the song rather than confining the accompaniment's independence to before and after the verses. Doubling a melody in the accompaniment is a common practice of Beethoven's, featuring in his songs of all kinds; but this sort of support for the singer was beginning to seem unnecessary and old-fashioned.

(Stevenson's arrangement) [29/30]

(Beethoven's arrangement) [29/30]

Beethoven's Viennese style and his own strong musical character are more jarring than the anonymously Italianate Stevenson. Neither of them sees much attraction in the modal nature of some of the airs they handle: Beethoven's second version of 'Highland Harry' (No. 6 of 12 Scottish Songs) shows him modernizing the tune by making continual use of the sophisticated chord of the dominant ninth rather than treating it as the 'antiquated' dorian mode. The modes were the old system of scales ousted by the 'invention' of keys in the seventeenth century. Beethoven must have made a conscious decision to bring the modal airs up to date by supplying contemporary harmony; his familiarity with modal practice is demonstrated by the slow movement of his String Quartet Op. 132. When Stevenson was confronted with modes (as in 'Avenging and Bright' and 'Lesbia Hath a Beaming Eye'), he reacted as Beethoven did and squeezed them into the nearest equivalent modern key; no doubt he regarded this as a form of musical refinement.

Like Stevenson, Beethoven arranged some of the airs for more than one voice but preferred a high voice to carry the melody even in a solo setting, whereas Stevenson favoured the middle-voice range which made his arrangements more accommodating to the untrained voices of amateurs. Stevenson's accompaniments were for piano only; Beethoven added parts for violin and cello. The added string parts were not popular, so Thomson urged a reluctant Beethoven to connsider the fashionable flute instead of the violin. The request helps to locate the [30/31] position of Thomson's project in Scottish cultural life; it illustrates the distance between the musical interests pursued by Thomson's middle-class patrons and the indigenous style of Scottish fiddling, promoted by the landed aristocracy, which was in its heyday. Beethoven only succumbed to the pressure to write for flute in his purely instrumental op. 105 and op. 107. In some ways these piano and flute variations represent Beethoven's most successful treatment of the airs he received: op. 107, no. 8, for example, shows an imaginative working in his distinctive late style.

Thomson engaged other composers, such as Hummel, Weber, and even Bishop (who had been the arranger for the three volumes of Moore's National Airs), yet in the end his publications met with limited success. In 1855 he sold off his entire stock cheaply to a music dealer. He must have noted with bitter irony how Tom Moore's 'Those Evening Bells', set to a melody attributed to Beethoven, had become a drawing-room favourite.

Burns and Moore had pointed the way ahead to the Scottish and Irish ballads of the Victorian period and to a refined pseudo-folksong. In the years immediately after Burns' death, Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) was collecting for his Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (three volumes, 1802-3), assisted by Joseph Ritson (1752-1803) and James Hogg (1770-1835). The latter, the son of an Ettrick farmer and often styled 'the Ettrick shepherd', made a determined effort to assume the mantle of Burns in his Jacobite Relics of Scotland (two volumes, 1819-20). The true successor to Burns, who produced a wealth of enduring Scottish songs, was Lady Carolina Nairne (1766-1845). She was named Carolina after Prince Charles Stuart, and became 'Lady' Nairne only after the revival of the Jacobite peerage in 1824 (one of the relaxing easures which followed Scott's invitation to George IV to visit Scotland two years earlier). Many other songs appeared anonymously in The Scottish Minstrel (1821-24). A collected edition, acknowledging her authorship, was published posthumously in 1846 as Lays/rom Stratheam (musical arrangements by Finlay Dun). Her songs are an innocuous blend of romantic and sentimental Jacobitism (as seen in 'The Hundred Pipers' and 'Will Ye No Come Back Again?').

As was the case with operatic airs, nostalgia was the favourite mood of the 'national airs'; the urban bourgeoisie felt no interest in the contemporary reels and jigs of figures of such central importance to Scottish fiddling as Niel Gow (1727-1807) at Blair Castle or William Marshall (1748-1833) at Gordon Castle. Rev.J. Riddle of Oxford, for one, was far more interested in further dignifying Lady Nairne's verse by translating it into ancient Greek. The second volume of Hogg's Jacobite Relics does contain verses written to 'Flora MacDonald's Lament', a violin tune by Niel Gow Jun. (1795-1825); and Lady Nairne supplied words to a tune by Nathaniel Gow (1763-1831), one of a series in which the fiddler intended to illustrate the street-cries of Edinburgh. In 'Caller Herrin' he attempted to portray the cry of the Newhaven fishwives set against the pealing of the bells of St Andrews, George Street.

From the desire to dignify a Celtic air to the wish to imitate one, or decorate a song with Celtic features, was a small move. Imitation Scottish song was not a new thing; James Hook's "Twas Within a Mile o' Edinburgh Town' is a well-known eighteenth-century example of pseudo-Scottish song. Products like Mrs Gibson's setting of Byron's 'Lochnagar' and Rev. William Leeves' setting of Lady Lindsay's 'Auld Robin Gray', however, signal a new departure which will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Last modified 11 June 2012