Two versions of Clytie, the terracotta at left in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the bronze in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. [Click on these images and those that follow to enlarge them.]

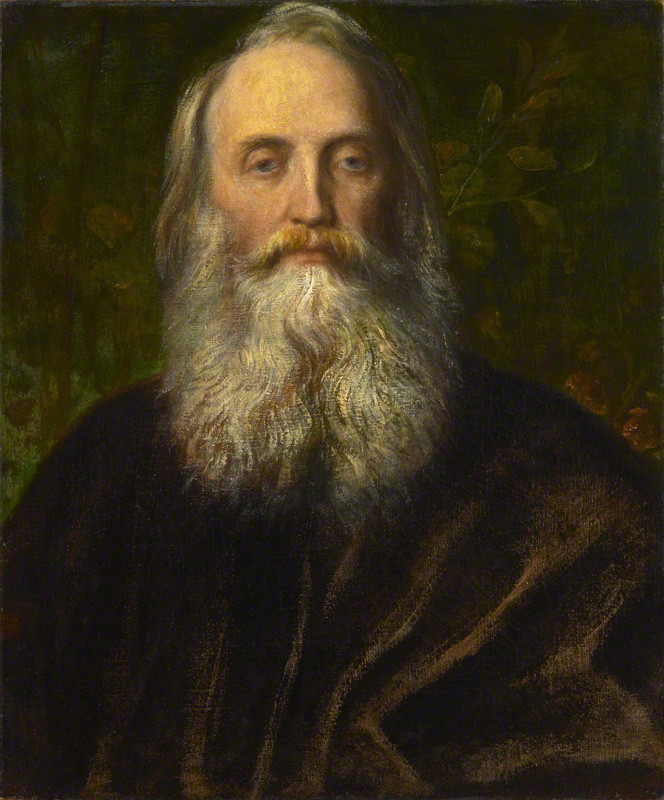

Mr. Watts is one of the Few modern artists who from the beginning of their career to the present time have been consistent in their aims. The wave of Pre-Raphaelitism, and the succeeding waves of neomedievalism, aestheticism, and realism, have passed over his head and left him unchanged and unmoved. He started with a distinct inner impulse — an artistic conscience of his own; and though no one has shown himself more widely sensitive to the spirit of the noblest schools of all time, he has permitted nothing to impair his individuality. In allegory or portrait, tiny sketch or colossal fresco, the expression of essential truth has been his one purpose. Idealism based upon thorough knowledge of material facts is the characteristic of all his work. The time that he spent in studying sculpture under Mr. Behnes has not only borne fruit in some fine plastic works — only one of which, the "Clytie," is shewn at the present exhibition — but in all his pictures: very notably indeed in the fine structural quality and accurate modelling of his portraits. He has always been devoted to the loftiest art. His earliest successes were achieved with vast historical cartoons which won prizes in the competitions (1843 and 1847) for the decoration of the Houses of Parliament. Evidence of his zeal in the cause of great art and his sense of its value in national education is found in his noble offer to cover the Great Hall of Euston Station (exterior) with mural paintings without remuneration. His large frescoes of the History of Justice in the Hall of Lincoln's Inn (exterior) was the result of a similar proposal to the Honourable Society, who not only accepted it in the spirit, in which it was made, but proved their admiration of the work by a present of £500 and a cup.

But notwithstanding all these achievements, and the number of fine imaginative pictures that he has exhibited at the Royal Academy, the Grosvenor Gallery, and elsewhere, it is as the most intellectual portrait-painter of the day that Mr. Watts is best known. It was in 1837, being at that time but nineteen years old, that he first exhibited at the Royal Academy; and his three pictures — two portraits and a "Wounded Heron " — were surrounded by work which was probably superior to them in technical skill. All the same, the art of England was at a low ebb, especially in portrait-painting; and there can have been little or nothing on view that a young painter might study or might imitate with advantage. The conventional style of portraiture which aimed at little more than giving a recognisable or a flattering likeness prevailed for many years. Only recently have we been able to leave off wishing that exhibition portraits could be banished, to some closed chamber only to be opened (like a dead-house) to persons in melancholy search for a relation. Now the portraits of the year are one of the most attractive parts of an exhibition. That this is so is mainly due to Mr. Watts. He was the leader of the reformation of portrait-art in England; he gave it a fresh inspiration and a new point of departure.

No one could have done this effectually without distinct and original aims pursued with persistence through many years. It was more difficult perhaps to be original in this, the oldest branch of art, than in any other. To say nothing of the old masters — Raphael and Titian, Holbein and Van Dyck, Rembrandt and Hals — a man of ordinary ability can be little but a distant follower who succeeds the great artists of the English school. But Mr. Watts is not a man of ordinary ability, and he struck out a path for himself which was not perhaps new, but which had been little trodden, and which soon led him far beyond the bounds of conventional art. I say it was not quite new, because all artists of all times have endeavoured to express the minds of their sitters. Few, however, if any, have pursued it so singly, so persistently, and so successfully as Watts. The special aim of his art has been to make the face the window of the mind.

With the ordinary portrait-painter the window is closely curtained: the only mental fact expressed of the sitter being that he or she is trying to look their best and to sit still. To present the sitter as unconscious of the presence of the artist was an advance indeed in the progress of the art, and in the work of some of our greatest painters it is only achieved by making him conscious of something else. Even Van Dyck and Hals never thought of doing much more. They employed their sitters in various pursuits, or they devised some transitory motive to give meaning and expression to their faces. Their portraits are occasional, dramatic, incidental. The pomp of circumstance, the dignity of office, the distinction of bearing, the magnificence of apparel, the casual smile, the employment of a moment, were all used to increase the pictorial effect and add to the triumph both of artist and subject. Not conscious of the presence of the artist, but very conscious indeed of the world and of future generations, to whom they wish to be represented at their best and bravest, are the sitters of the past. Such unconsciousness as theirs — in which the mind is indeed at ease, but only partially freed from the constraintsof the outer world — has not satisfied Mr. Watts, nor has he sought so much to dress his sitters as to express them. The only accident of which he makes use is that of music: the power of which to unlock the soul is finely shown in his portraits of Herr Joachim and Lady Lindsay, and once or twice elsewhere. No deportment however brave, no gesture however elegant, no attitude however graceful, no employment however picturesque, has diverted him from his more serious purpose. The "happiest" expression has no charm for him, unless it be also the truest; he had yielded nothing to the vanity of his subject, or his own. Not how a man or a woman may wish to appear before the world, but what she or he is in her or himself, has been his business. Not with the curtains partially withdrawn, but withdrawn altogether, does he seek to portray the face; so that, whether from sweetness of disposition or nobleness of thought, whatever there may lie of inner light may shine through. Other artists have drawn men and women more bravely in society, but none has painted them more completely as at home: at home, not physically but mentally; and not only at home, but alone.

Mrs. Frederick Myers

It cannot be doubted that this strict adherence to his high intention has been attended by no small sacrifice of his natural pride in technical skill — perhaps the greatest sacrifice that a painter can make. He seldom paints more than a half-length; he frequently conceals the hands, and this, not from any want of power, but the desire to concentrate attention on the face, while the face itself is painted so as not to call attention to the skill of the execution; and, when freshly done, his surfaces have a somewhat rough and crude appearance, as of fresco. Like the author of a play, he is not on the stage; he is only called for when the play has been enjoyed. How great and consistent a sacrifice his practice must involve is shown best by almost the only example amongst his portraits in which he has put forth all his painter's power to charm the eye with glory of colour and rhythmic stateliness of line. In his portraiture of the Hon. Mrs. Percy Wyndham he has employed every resource of his art to express, not only character, but physical charm. The scale of colour is not brilliant, but it is rich exceedingly; the dead red of the vase and the brown and green and cream of its magnolias are not in more perfect harmony with the rich dress and clear pale complexion than their grand rounded forms with the noble graces of the beautiful figure. Of itself this superb achievement is enough to show that it is not because the painter could not have rivalled other masters on their peculiar ground that he has chosen to keep to his own. His portrait of Mrs. Frederick Myers, which we have engraved, is more in his wonted manner. It is a characteristic specimen of his capacity to render not only outward visible form, but the inward beauty of the spirit also.

It is, however, in his presentments of public character that he has attained his greatest distinction both as a man and as an artist. It is in these that his special faculty has found its fullest scope. There is not one that does not testify to his unrivalled power of mental diagnosis, not one that does not stamp him as a leader amidst the intellectual forces as well as amidst the painters of his generation. His collective achievement is a most vivid and enduring record of the number and variety of noble minds which have been at work in England during the last quarter of a century. It is not only wonderful in itself; it is not only rarely and loftily beautiful. It is in the truest sense national; it demands not only the admiration of the critic but the gratitude of the citizen. I doubt if public money could be more properly or patriotically spent than in securing replicas of every item in the sum for the National Portrait Gallery.

In the present article I can do little more than call attention to the extraordinary faculty, at once intellectual and emotional, which has enabled one man to set himself in tune with so many and so various minds of a high order. In none of these portraits of men representing the spiritual and intellectual forces of this Victorian age has the artist failed to strike the key-note. A past of anxious search through metaphysic mazes for the truths most desired of mankind is written in the thought-worn face of Dr. Martineau, a future of passionate unrest and irrepressible individualism in the eager, subtle, self-conscious features of Gladstone in his prime. In Arthur Stanley we see the sensitive lip almost trembling with its message of good-will towards men; in Lord Lawrence, the man of thought as well as of action, the devoted and able servant of his country, the soldier and statesman in one. Here, the distinetive nobleness of each preserved, is the quiet definite Mill opposed to the thundering indefinite Carlyle.

Three of the portraits Monkhouse mentions — left to right: (a) John Stuart Mill. (b) Thomas Carlyle. (c) William Morris [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

These few words may give some notion of the breadth of Mr. Watts' sympathy, and of the unerring certainty of his insight. To detect his finer discriminativeness, some special and peculiar class of portrait should be studied. No class will serve this purpose better than that of the poets; for the mental characteristics of the sitters are widely known, their number is small, and all the greatest of them are here. Of Tennyson there are two portraits; one taken in 1859, the other recently. In both there is a touch of mystery which is wanting in the presentments of the sitter's brethren; in both there is a something of the seer and the philosopher — a something of the fastidious workman who is long in seeking out the best. The powerful head is a laboratory where thoughts volatilise m passion, and ion is absorbed in thought. The fire of genius that one rather feels than sees, smoulders long sometimes before it bursts into flame; but to look at Mr. Watts' portraits is to be as sensible of its presence as of its safe control. The later work in nowise contradicts the earlier, it is rather the proof and fulfilment of it; passion, imagination, and reflection are the chords of both. On the others I have not space to enlarge. I shall only note that in each particular face the painter has shadowed forth some special and peculiar characteristic: in Browning's, speculation; in Swinburne's, ardour; in Taylor's, reason; in Arnold's, criticism; in Morris's, taste.

Three of the portraits Monkhouse mentions in the preceding paragraph — left to right: (a) Robert Browning. (b) Sir Henry Taylor. (c) Algernon Charles Swinburne [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

It is one of the properties of genius that its processes are too subtle and complicated for analysis; and how Mr. Watts is able to inspire his faces with all this "psychic" force must he to some extent a mystery. To recur to my former images: he has made them truly the windows of the minds, he has withdrawn the curtain, he has painted them at home, mentally and alone. One thing, however, we may take for granted: that he has no charm by which he can at will shade off the minds of his sitters from all the reflections of daily life. Even if he could effect the necessary isolation, it is not probable that he could produce the desired expression. His process is very different from this; and if we cannot analyse it perfectly, we may at hast conjecture that a wider sympathy, a power to sift what is essential from what is incidental, a spiritual insight almost amounting in some cases to divination, are among the agencies he sets at work. Most portraits deal but with present facts. His are inspired with that large truth which is perceived only by the imagination; they extend far hack into the past, and far forward into the future. The Martineau and the Mill are histories; the Gladstone and the Burne-Jones are not only histories, but prophecies.

It is evident that a man who can paint such portraits as these is not only an artist but a poet. It is probably not entirely from inclination that Mr. Watts has devoted comparatively little time to purely poetic art, of which he has given us specimens of noble originality and of so rare a quality that there are few great artists of any time to whom he has not been compared by writers in England and on the Continent. For all that, in his creative, as in his portrait art, he remains himself; he is as individual as he is versatile in bringing the same serious and imaginative intelligence to bear upon his work, whether it he the presentment of a poet's face or the embodiment of some one of his dreams. That his genius as an artist in imagination is not duly recognised is sufficiently proved by the fact that one of the noblest imaginings ever painted — his "Paolo and Franceses" — still remains in his own possession. This is no doubt partly from the insensibility of the British public to any but the most commonplace sentiment in art, partly because of their reluctance to believe that one man can excel in more than one thing. At the same time it must he confessed that of epic work he has finished but little, and that he has too frequently exhibited designs which, however suggestive of power and loftiness of purpose they might be, were likely to be neglected in the presence of his fully wrought portraits. A few he has completed worthily which, when once seen, live for ever in the memory as things apart: from the noblest as from the most trivial expressions of contemporary art. It is needless to institute comparisons between him and any of his great contemporaries; it will be sufficient to say that the quality of emotion and enjoyment to be derived from his pictures is unusually varied and noble. As needless is it to compare him with the dead; it will be enough to note that to the Venetians he seems to owe his mastery of decorative effect, and some of his sense of the heroic dignity of the human form, while his daring in conception and rare power of bodying abstract ideas in grand and simple forms have been strengthened by the study of Michelangelo.

Diana and Endymion

A student of the dead rather than a rival of the living, above all is he indebted to the Greeks. Classic legend it is that has supplied him with the subjects of perhaps his most perfect pictures. In his "Daphne" he has not chosen to give us any incident of the beautiful old myth — not the flight from the god-lover, not the supplication nor the blossoming. The figure of the hapless nymph — naked, and chaste, and pale, against an exquisitely drawn and composed background of laurel — is an allegory; of sylvan purity, it may be; in any case of beauty. His splendid "Wife of Pygmalion," a veritable "translation from the Greek," and his most excellent design of the "Three Goddesses," naked and unashamed, wearing that air of divine dignity which was not reborn at the Renaissance, might almost be described as art before the Fall. There is more of modern sentiment in his sweet, shrinking figure of "Psyche; and it is of the art of Venice rather than that of Athens, of which we are reminded in his lovely vision of "Endymion," which we have engraved. He has proved his sympathy, too, with the fancies of more than one of the moderns. His "Ophelia," craning over the dark stream, mind and body burnt out with the fierce pale flame that still flickers in her wan cheeks and wild eyes, is very finely conceived; but in "Paolo and Franccsca " we have one of those rare pictorial visions which seem identical with those of the poet they illustrate. The lachrymose sentimentalism of Scheffer and the theatrical posturing of Doré are equally foreign to the stern impassioned quiet of the great Italian. Here, though, we see what Dante saw. Here we are overpowered, as he was overpowered, with the sense of the irrevocable, the hopelessness sublime, the terribleness of love dead and fruitless but everlastingly potent. There are the lovers; and there is Eternity. Will-less and hopeless in the windy void, there are they wafted together for ever.

Three allegories not mentioned by Monkhouse — left to right: (a) Death Crowning Innocence. (b) Love and Life. (c) Time, Death, & Judgment [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

The painter's tendency to express the mysteries of life in allegorical design — though seldom shown till recent years — commenced early, if I may rightly presume that his notable composition of "Life's Illusions" (exhibited in 1849) was not its first result. Considered either as a piece of flesh-painting or an achievement in design, this glorious vision of illusive beauty rising and curling and vanishing like vapour has not many rivals in modern art. The rest of the allegory is a little obvious — as young men's allegories are wont to be. Mr. Watts' next ambitious work of the kind is the grandly decorative "Allegory of Time and Oblivion." It would seem to be the artist's earliest presentment of his original and lofty idea of Time — not as our withered white-haired enemy with the forelock, but, in his own words, "as the type of stalwart manhood and imperishable youth." The idea is repeated in his "Time and Death," of which "only a sketch is on view. For Death, too, he has invented a new image: as of a greal woman, while robed and of ghastly complexion, with hollow cheeks and sunken eyes. In the far finer design of "Death and Love," he has apparently expressed the same idea: but the figure is draped from head to foot, and has a wonderful suggestion of a mysterious irresistible Force, all the more awful because impalpable. This picture has been greatly improved since it was first exhibited, and its dryness of texture is softened by the glass in front of it; but it has not, to me, the same beauty as the exquisite small finished study of the composition which is in the larger room. Yet another aspect of his female Death has Mr. Watts portrayed for us in the elaborate composition called "The Angel of Death," where she is painted sovereign and enthroned. The work is grand, monumental, and — as will he seen from the careful explanation which is given in the catalogue — full of poetic intentions. I doubt, however, if a picture which needs so much of verbal assistance for its right interpretation is ever worth painting.

To All Churches: a Symbolical Design, 1875

Much the same objection attaches to the "To All Churches: a Symbolical Design, 1875," of which we give an illustration. It represents the Supreme Being in a symbolic form, neither male nor female, gathering together his children, the Churches (all forms of belief), as a hen gathers her chickens under her wing. It is a spectacle designed to show that all the disputes of all the creeds are but as the quarrels of children in the sight of God, and so to shame mankind into tolerance. A sermon, a satire, and a poem in one, it is lofty alike in motive and idea. At present the colour is crude and unpleasant; but it is probable that a few years will produce a change in this respect, if one may judge by the effect that time has had on a good many of its fellows. And here it may not be improper to note that Mr. Watts in his method of painting shows the same originality and serious purpose as in his design, preferring to lay his tints side by side, like mosaic, to painting one over the other. He mingles them, of course, at the edges; but he never puts light or bright colour over darker. He never, when he can avoid it, mixes white with transparent lines, but makes the substance of his colouring of those that have the greatest transparency and least body: his theory being, that when in course of time the preserved brilliancy of the ground tells through, his pictures will have the quality of stained glass. He is also careful that his colours should in themselves be beautiful, and he lays them on thick and dry, with very little medium. It may be interesting to state that the medium he uses is linseed-oil, if necessary diluted with some essential oil. How far his theory is justified by the event is illustrated by several of the pictures exhibited, which, though he has not touched them since they were painted, are far fresher in appearance and more luminous in colour than most of his later works. It may be doubted whether there is not a little too much of the stainedglass quality in his "Lady Holland;" but I know of no modern picture which has such a splendid body of pure bright colours as his "Lady Playing the Piano, 1860." The earlier portrait of Tennyson is one of many others which have similarly improved. Should the "To All Churches" ever glow with the same inner light, it will not indeed better the text of the sermon, but the delivery will be far more effective.

Of Mr. Watts' future work it is hard to prophecy. Of dreams and designs already sketched out there are enough to employ him for many years. It is earnestly to be hoped that some, especially the "Three Goddesses," will receive more perfect realisation. Among them are many inspired by Scripture: as, for instance, the grand and gloomy Esau, and that most tremendous vision of the wrath of heaven descending upon Cain. Of this latter only the sketch is here; the picture is deposited in the Diploma Gallery of the Royal Academy. The two projected series of the "Fall of Man" and the "Life of Eve" are full of fine promise, and the scenes from Revelation are quick with germs of greatness. Meanwhile, to whatever work Mr. Watts may turn his hand, we may be sure that nothing small or ignoble will ever come from under it.

The Mid-day Rest.

Certainly neither of these epithets can be applied to the last work on my list — the subject of our full-page engraving. This noble picture — "The Mid-day Rest," as it is called — is not of a kind that one would have expected from Mr. Watts. But, with its frank and semi-heroic realism, it expresses an intention quite characteristic and quite worthy of the artist — that of the preservation of faithful images of grand and unique types both of man and horse, which he thinks may ere long be refined away. To this end has he painted to the life his brawny, beery, herculean drayman, leaning against his shafts and sleepily casting grain to the pigeons, while his grand docile brutes stand patient and still. The painter, as may be seen in many of his pictures, has studied animals with great care and to admirable purpose; but there is still reason for surprise at the splendid modelling and grand drawing of these magnificent horses. The same sense of fitness which characterises all his work is evident in the background of broad horse-chestnut leaves and red-brick wall, in harmony with the grandiose simplicity of the whole design.

Bibliography

Monkhouse, Cosmo. “The Watts Exhibition.” Magazine of Art. 5 (1882): 177-83. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 23 October 2014.

Last modified 23 October 2014