Unless otherwise mentioned, photographs are by the author. [Click on images to enlarge them.] You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

The pace of new building in the City of London quickens. As you walk down Bishopsgate in the direction of the Monument (to the great fire of 1666) one could be forgiven for thinking that steel and glass have taken over entirely. But there remain some remarkable nooks and crannies and one of these is the network of alleyways behind St Michael’s Church, Cornhill. Here stands the Jamaica Wine House on the very same spot as its more famous predecessor the Jamaica Coffee House.

Left: The Jamaica Wine House. Right: The modern entrance. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In The City or the Physiology of London Business (1845), David Morier Evans tells us that

The Jamaica Coffee House is to the West India trade what the Jerusalem Coffee House is to the East India trade. The proprietors and managers of the Jamaica Coffee House pride themselves upon the accuracy and full extent of their West India intelligence quite as much as the Jerusalem people pride themselves upon the accuracy and full extent of their East India intelligence. These two establishments may be said to afford a fair specimen of the attention that is paid in houses of this description, to secure an independent footing by supporting a particular interest. The Jamaica Coffee House is situated in St. Michael’s Cornhill, and the number of subscribers varies from two hundred and fifty to three hundred and fifty, the parties being the merchants engaged in commerce with Madeira and the West Indies, who assemble together for business purposes before going to their several counting-houses in the morning, or after leaving [The Royal Exchange] in the afternoon. The subscription-room in this establishment is exceedingly commodious; and the supply of papers and shipping-lists published in the localities it represents, is numerous and well-selected. It is the best place, above all others, to ascertain any information relative to the mail packets on the West India station, or the merchant-vessels making these voyages. There is in this, as well as in the other rooms of the same description, in the city, a sandwich-bar; so that refreshment, in the shape of tea and coffee sandwiches, and wines and liquors, is often combined with business pursuits. [149-50]

Left: . Right: A nearby alley with an evocative name. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

There were over a thousand coffee houses in London but a select few focussed on the needs of the London merchants trading at the nearby Royal Exchange and Lloyds. Miller (p.45) and Pope (p.102) disagree slightly on the dates but coffee seems to have entered Europe by Italy (probably by Venice) in 1645, and in 1652 (or 1657) the first coffee house was established in London by a Greek, Pasqua Rosa probably in St. Michael's Alley, Cornhill, near the present Jamaica and Madeira coffee house.

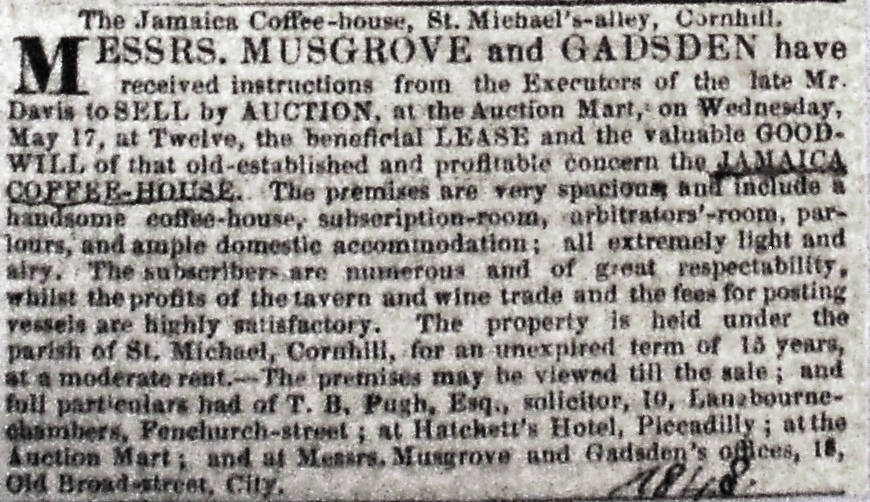

Left: An 1848 advertisement. Right: The Royal Exchange. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Presumably Rosa’s coffee house was destroyed by the 1666 conflagration but it miraculously escaped the fire of 1748. According to the London Magazine “About One this Morning, a fire broke out at Mr. Eldridge’s a Perriwig-Makcr in Exchange Alley, Cornhill, which proved one of the most terrible, before it was extinguished, that has happened since the Fire of London in 1666. The flames in a few minutes spread themselves three different Ways, and before Noon consumed, according to the best computation that could be made, very near 100 Houses, about 20 of which fronted Cornhill... the Jamaica coffee house was but little damaged, as was likewise St Michael’s Church” (p.140).

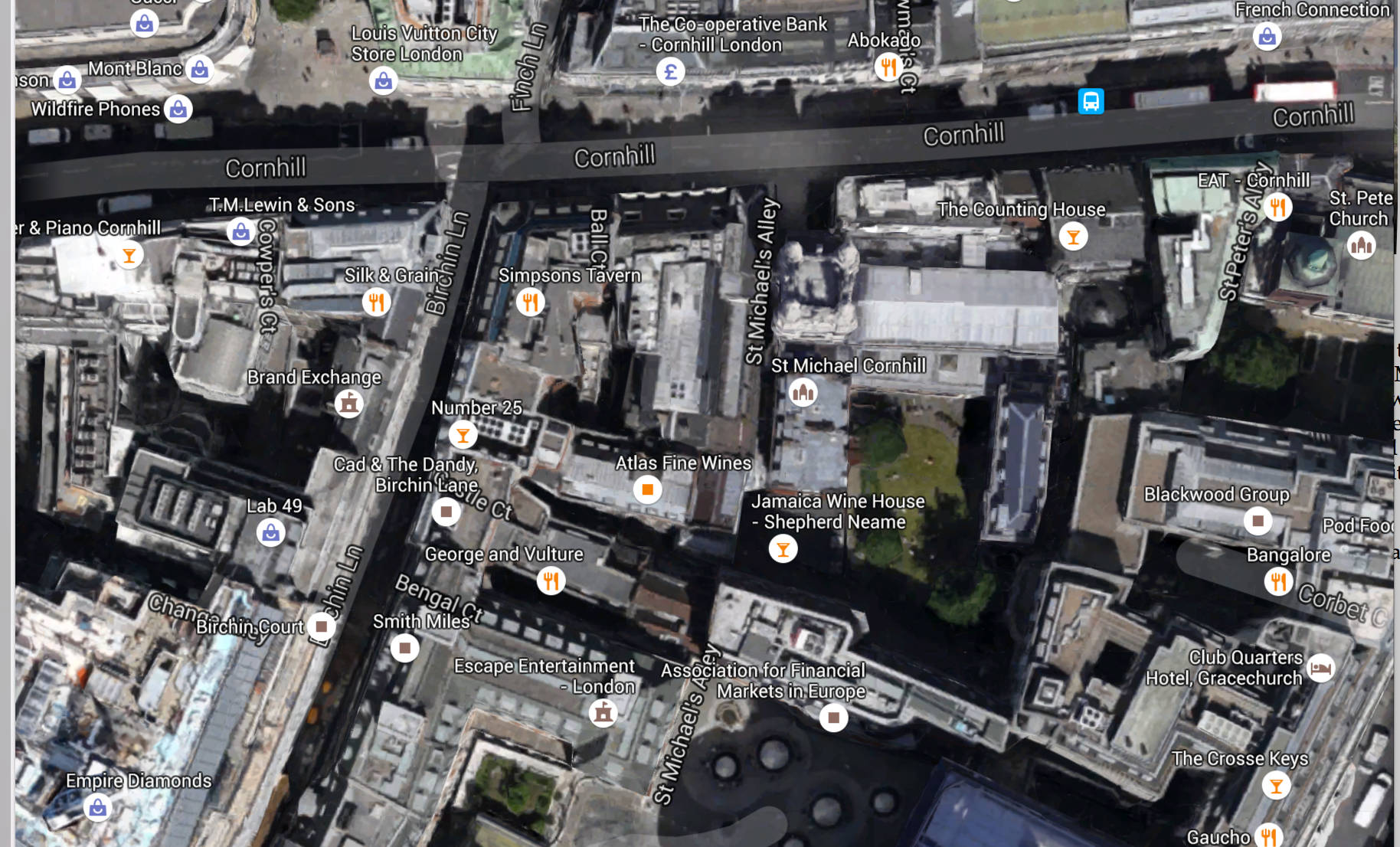

The location of the Jamaica Coffee House (now Wine Bar) on a Google Maps satellite photograph.

By 1805 there were several of these mercantile coffee houses in the vicinity of the Royal Exchange and Lloyds. “The Picture of London for 1805” provides a list; (p.352)

Africa and Senegal Coffee house, St. Michael's Alley, Cornhill. Frequented by merchants and captains trading to those parts. Dinners from two to five every day. Good wines and lodgings.

Jamaica Coffee house, St. Michael's Alley, Cornhill Frequented by West India merchants, Etc. Dinners dressed, and beds made up or procured.

Jerusalem and East India Coffee house, Cowper's Court, Cornhill. Frequented by merchants and gentlemen concerned in the East India Company's service. Tontine [investment] Office. Fitted up in an elegant style for the use of the subscribers.

Virginia and Maryland Coffee house, Newman's Court, Cornhill. Frequented by merchants, &c. trading to those parts. Good dinners and beds.

Carolina and Honduras Coffee house, Birchin lane, Cornhill. Frequented by merchants, &c. trading to America. Dinners dressed in the afternoon,' and beds made up or procured. Excellent punch.

Will's Coffee house, Bank Buildings, Cornhill. Frequented by merchants, brokers, Etc trading to Spain and Oporto. Dinners dressed in the afternoon and beds, procured.

Bank Coffee house, opposite the Bank. Frequented in general by the stock brokers and Bank clerks. Dinners dressed, good wines, &c.

Stock Exchange Coffee house, over the Stock Exchange, in Threadneedle street. Frequented by merchants, brokers, and mercantile people in general. Excellent dinners at a reasonable price every afternoon, and beds procured.

American and New England Coffee house, Threadneedle street. Frequented by merchants, &c. trading to New England. Dinners dressed every afternoon, good wines and beds made up or procured.

Lloyd’s Subscription Coffee house, over the west end of the Royal Exchange, Cornhill. Frequented by merchants, underwriters, insurance, Mock, and exchange brokers, &c.

A humorous sketch in a French magazine, Le Globe, gives us an idea of what went on in these mercantile coffee houses:

The Jerusalem Coffee House is the rendezvous of owners of ships engaged in the commerce of India. A stranger, who enters it for the first time, is struck with astonishment at seeing a crowd of men moving around him with a kind of mercantile fury; he hears resound on all sides the words cotton, indigo, rice, insurance, hills of lading, cargo; he is every moment pushed by his neighbour, who is endeavouring to join those whom he has appointed to meet. A boy stands in a corner of the room to give the address of different captains, and to inform strangers of the hour at which they generally visit the Coffee House. The walls are covered with hand-hills and printed placards, which specify the time at which the different vessels set sail, and describe all the advantages of their fitting-up; in order, however, that you may he still better able to judge of this, very detailed plans circulate from one table to another. One vessel is to leave positively in six days; another will set sail with all the speed possible; a third has almost all her cargo on board; a fourth has still two cabins to let; you must he quick, for you risk the not being able to procure a passage. A person who is not initiated in the customs of the the Jerusalem Coffee House really hastens to make a choice; he makes arrangements with one of the owners, and pays in advance; he is assured by him that the vessel will sail at the time specified in the advertisement, and recommended to hold himself in readiness. The time arrives, hut the vessel still remains on the stocks, and the deceived passenger lingers for weeks, and sometimes even for months, every day expecting his departure. But the experienced voyager after having read the announcements at the Jerusalem Coffee House goes to the City Canal to see the vessels, and judge for himself when it will be possible for them to put to sea. He sees the first in the hands of the caulkers, without' rudder, and without main-mast. The second is about to be put into dock because she has sprung a leak. The third is discharging her old ballast in order that they may clean out the hold; and, as to the fourth, the carpenters are on the point of beginning to construct a poop, and to build new cabins. Seeing this, he quits London and goes to make a tour on the Continent or to pass four or five weeks in Scotland; and, at his return, he finds that some of the vessels are ready to quit the port, and that the half of their cabins are still at his disposal. [Translated by the Oriental Herald 284]

Related material

Further reading

Evans, David Morier. The City or the Physiology of London Business. London: Baily Brothers, 1845.

Miller, John. The London librarian and book buyer’s gazette. London: Miller, 1853.

Pope, Charles.The Merchant, Ship-Owner, and Ship-Master's Custom and Excise Guide. London: Baldwin, 1831.

The London Magazine and Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer. London, 1748.

The Oriental Herald 8 (January 1826): No 25. London, 1826.

The Picture of London for 1805. London: Phillips, 1805.

Last modified 18 December 2015