The following essay appears in the 1894 edition of the Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. The epigraph comes from G. M. Young (see bibliography). George P. Landow scanned, adding paragraphing and boldface type, formatted in html, and linked the text.]

The great ritualist controversy’s . . . originating issue was the fashion of the preacher’s garment. The custom at the end of the morning prayers had been for the minister to retire and reissue from the vestry in the black gown of a learned man. As the practice spread of reading the Ante-Communion service after the sermon, the double change from white to black and back into white again was felt to be unseemly. But preaching in his whites — his vestments as a minister — the parson might be thought to claim for his utterances an authority more than his own, the authority of a priest, and so surplice riots became a popular diversion of the forties. . . . But gradually new standards of dignity, reverence, and solemnity assimilated the worship in the ancient meeting-place of the village, the portentous assembly room of a London parish, and the Gothic churches which were rising by hundreds in the populous suburbs and industrial towns. Protestant vigilance was easily alarmed, but even an Ulsterman could hardly suspect that the hand of the Pope was at work when the Communion Table ceased to be a depository for hats, the font a receptacle for umbrellas. — G. M. Young, Victorian England: Portrait of an Age

Introduction

Ritualism, a term popularly applied to a movement in the Church of England, and in the Protestant Episcopal Church. The revival of ecclesiastical learning, which was so conspicuous a feature of the Tractarian (q. v.) movement, necessarily made the clergy better acquainted with the primitive liturgies, and with the ancient service-books of the Church of England. This study of ecclesiology, as the science came to be called, was soon brought to bear upon the restoration of old churches and the construction of new ones, as well as upon the service of the Church. There was also the feeling that prayer, praise, and the holy eucharist are offered to God, as well as used for the spiritual advantage of man. It was under such circumstances, and under such influences, that " Ritualism" took its rise.

The Three Main Principles of Ritualism

The principles of Ritualism, according to its advocates, are three. They say, in the first place, that it rests on the declaration of the Convocation of Canterbury (1571), "that preachers should, in the first place, be careful never to teach anything from the pulpit, to. be religiously held and believed by the people, but what is agreeable to the doctrine of the Old and New Testaments, and collected out of that very doctrine by the catholic fathers and ancient bishops." This was thought to establish the doctrinal identity of the Church of England with the primitive Church. Consequently the apostolic episcopate and sacramental grace are specially insisted on, baptismal regeneration is strenuously asserted, and the holy eucharist has been made the central object of teaching and the highest object of worship. The voluntary use of private confession and absolution as a preparation for the reception of the holy communion has also made considerable progress,

The second great principle of the Ritualist is stated in the thirtieth canon: "So far was it from the purpose of the Church of England to forsake and reject the churches of Italy, France, Spain, and Germany, or any such-like churches, in all things which they held and practiced, that, as the apology of the Church of England confesseth, it doth with reverence retain those ceremonies which do neither endamage the Church of God nor offend the minds of sober men." This principle, it is alleged, establishes the fraternal readiness of the Church of England for visible union with other branches of the apostolic Church, and the Ritualists assert a willingness to do any and every thing lawful to approximate towards the Continental Church.

The third principle is found in the Ornaments Rubric: "The chancels shall remain as they have done in times past . . . that such ornaments of the church and of the ministers thereof; at all times of their ministration, shall be retained and be in use as they were in this Church of England, by the authority of Parliament, in the second year of the reign of king Edward VI." This was interpreted to mean that the chancels, vestments, ornaments of the church and ministers, should be the same as before the Reformation. This principle was fully developed at several churches in London, Oxford, Leeds, and elsewhere.

Depending upon the above-mentioned principles, there are six chief points insisted upon by the Ritualists:

1. the eastward position of the celebrant in the sacrament of the holy communion, with his back to the people;

2. the eucharistic vestments;

3. lights, burning at the time of celebration;

4. incense;

5. the mixed chalice, a little water being mixed with the wine:

6. unleavened (or water) bread.

The Directorium Anglicanum, being a manual of directions for the right celebration. of a holy communion, for the saying of matins and evensong, and for the performance of other rites and ceremonies of the Church, according to ancient uses of the Church of England, by the Rev. John Purchas. was published in 1858. A full development of ritualistic usages on the principle thus indicated was established at St. Alban's Church, Holborn, and at a later date at a Brighton chapel, of which Mr. Purchas became incumbent. The ceremonial of divine service was raised to a much higher standard than had been contemplated by the older school of Ritualists, and provoked opposition from them. for it was chiefly copied from modern Continental customs, and was much mixed up with a sentimentalism about candles and flowers, as well as with an excessive minuteness in regard to postures and gestures, which made it easy to charge the school with trifling and want of manliness.

Victorian Opposition to Ritualism

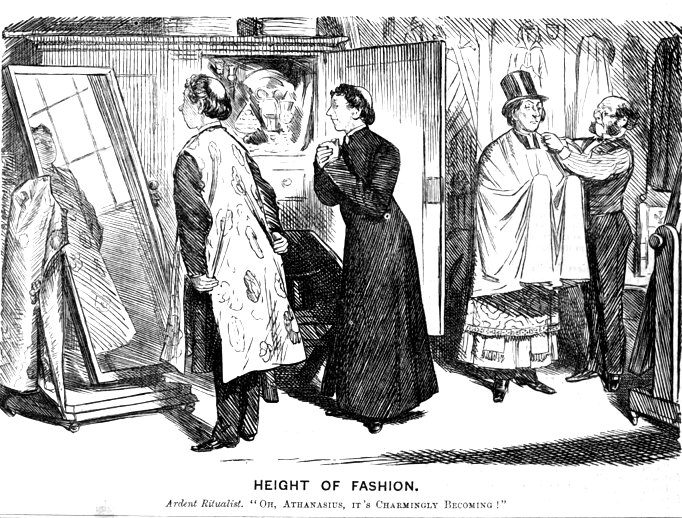

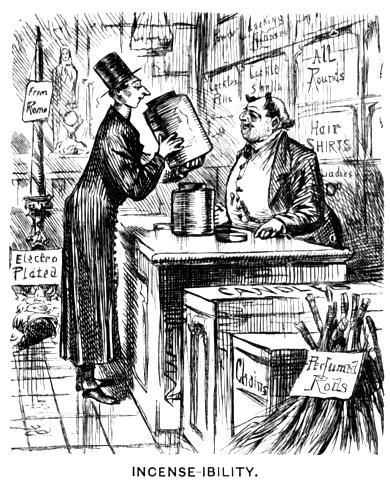

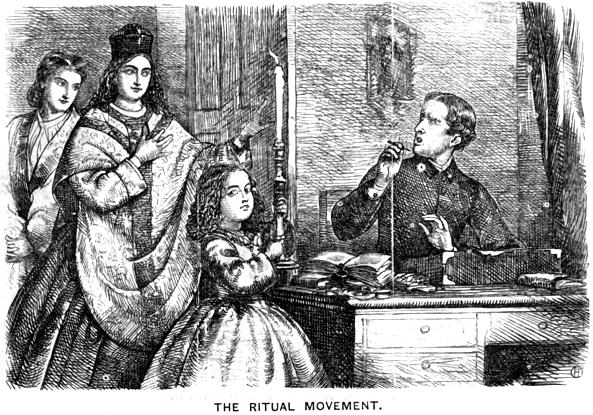

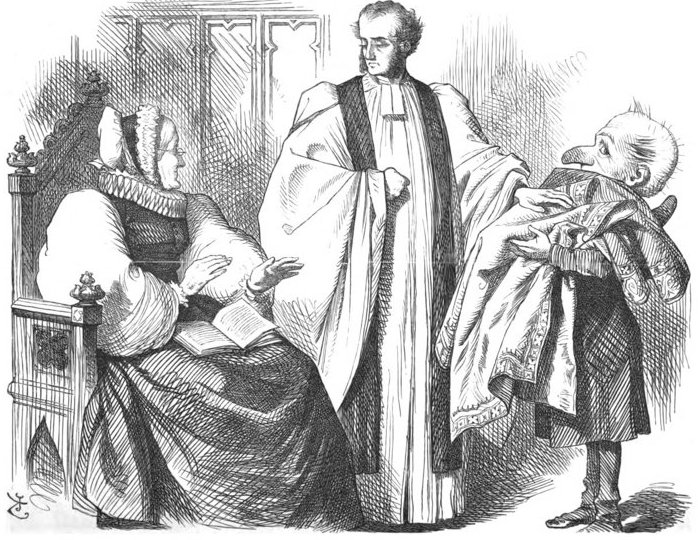

Four 1866 Punch cartoons satirizing Ritualism as effeminate and merely fashionable. Left: Height of Fashion. Middle left: Sweet Thing in Christmas Vestments. Middle right: Incense-ibility. Right: The Ritual Movement. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

There have been a number of legal cases arising out of the teaching and practices of the Ritualists. The Church of Barnabas, Pimlico, was opened in 1850 for the purpose of carrying out completely and honestly the principles of Ritualism. This led to litigation, which ultimately brought both advocates and opponents before the Privy Council in 1857. The council considered some portions of the furniture of the church to be unsanctioned by the existing law, but the principle then contended for by the Ritualists was affirmed by their interpretation of the Ornaments Rubric, respecting the various forms of which they decided that "they all obviously mean the same thing, that the same dresses and the same utensils or articles which were used under the First Prayer-book of Edward VI may still be used." This decision left the Ritualists in possession of the field. Suits were also instituted against Mr. Mackonochie, vicar of St. Alban's, and Mr. Purchas, incumbent of St. James's Chapel, Brighton, which were carried up to the Privy Council, and all the six above-mentioned usages, and some others, were condemned.

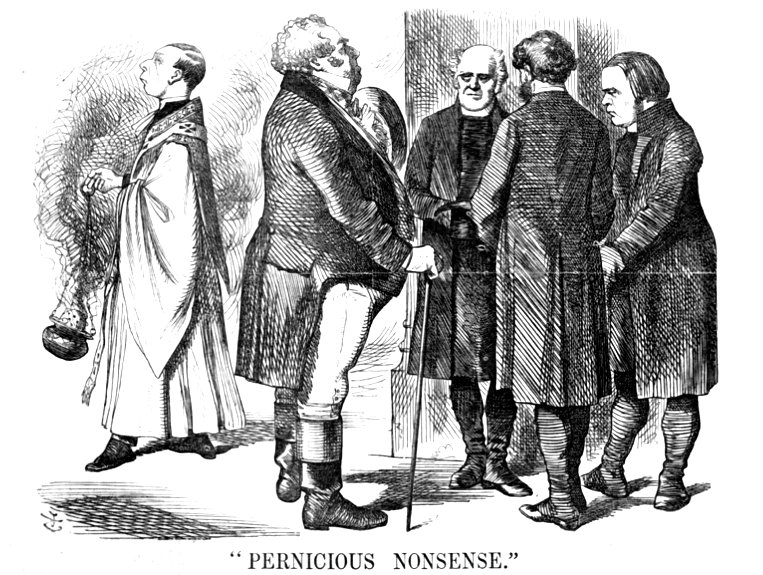

Three 1866 and 1867 Punch cartoons satirizing Ritualism as essentially Roman Catholic and therefore outside the Protestant tradition. Left: Pernicious Nonsense. Middle: A Change for the Better . Right: Over the Way. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

Of more importance than these cases was that of the Rev. W. J. E. Bennett, vicar of Frome, who published a sermon in which he taught "the real and actual presence of our Lord, under the form of bread and wine, upon the altars of our churches." The Court of Arches, through Sir Robert Phillimore, decided in Mr. Bennett's favor, and the appeal to the judicial committee of the Privy Council was dismissed by them (1872). In 1867 a royal commission was appointed "to inquire into and report upon different practices which had arisen, and varying interpretations which were put upon the rubrics, orders," etc; also to reconstruct the tables of lessons used at morning and evening prayer. Its reconstructed lectionary was authorized for use by Parliament and Convocation (1871).

The Ritualists have paid great attention to the study of the liturgies and rituals of all ages, and to that of hymnology. They have encouraged the revival of religious orders, and have communities of women devoted to labor in hospitals and like institutions. The ritualistic movement of England has received more or less sympathy in the United States, but with much less development of detail. In 1874 a general canon was passed, which was regarded as a nearly unanimous expression of opinion unfavorable to ritualistic extremes, but no occasion has arisen for putting it in force.

Related Material

Bibliography

M'Clintock, John, and James Strong. Cyclopædia of Biblical, Theological, and Ecclesiastical Literature. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1894.

Young, G.M. Victorian England: Portrait of an Age. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1953.

Last modified 13 June 2018