The following explanation of the origin of many of the changes at present going on on the earth's surface, was suggested in endeavouring to account for the very singular phenomena presented by the temple of Jupiter Serapis, at Puzzuoli, near Naples. The facts relating to that temple were observed by me in 1828, and the theory occurred soon after my return to England; but though occasionally mentioned to geological friends, it was not printed until it appeared in the abstract of my paper on the Temple of Serapis, presented to the Geological Society of London, in March 1854.

The following positions are taken as the basis of the reasoning on this subject: — [209/210]

1. That, as we descend below the surface of the earth, the temperature increases.

2. That solid rocks expand by being heated; but that clay, and some other substances, contract under the same circumstances.

3. That different rocks and strata conduct heat differently.

4. That the earth radiates heat differently, at different parts of its surface, according as it is covered with forests, with mountains, with deserts, or with water.

5. That existing atmospheric agents, and other causes, are constantly changing the condition of the surface of the globe.

The only one of these propositions on which, in the present state of knowledge, the slightest question can be raised, is the first. But the observations on which it depends have latterly become so numerous, that the general fact of an increase of temperature, in descending through the crust of the earth, can scarcely be questioned; although the exact law of this increase, and the extent to which it penetrates, are yet undecided.

An increase of 1° Fahrenheit's thermometer, for every 50 or 60 feet we penetrate below the earth's surface, [212/213] seems nearly the average result of observations. If the rate continue, it is obvious that, at a small distance below the surface, we shall arrive at a heat which will keep all the substances with which we are acquainted in a state of fusion. Without, however, assuming the fluidity of the central nucleus, — a question yet unsettled, and which rests on very inferior evidence1 to that by which the principles here employed are supported, — we may yet arrive at important conclusions; and these may be applied to the case of central fluidity, according to the opinions of the inquirer.

If we consider the temperature of any point: — for example, G, situated two miles below the surface of an elevated table land, A, in the annexed wood-cut; and if we imagine a surface passing through all the points of equal temperature within the globe; then, as this surface passes under the adjacent ocean, which we may suppose, on an average, to be two miles deep, it is evident that the surface of equal heat will descend towards the earth's centre; because, if it did not, we should have great heat nearly in contact with the bottom of the sea. In the first figure, B is the surface of the ocean. A D, the surface of the land, and of the bed of the ocean. The broken line, G F, is the isothermal line. Let us now [213/214] suppose, by the continual wearing down of the continents and islands adjoining this ocean, that it becomes yearly filled up. The broken line C, in the second figure of the wood-cut, indicates the new bottom. The former bottom of the ocean being now covered with a bad conductor of heat, instead of with a fluid which rapidly conveyed it away, the surface of uniform temperature will rise, slowly but considerably, as is shown at G E, in the third figure. In the fourth figure, the first bed of the ocean, A D, and its isothermal line, G F, as well as the new bed, A C, of the ocean, and its corresponding isothermal line, G E, are all shown at one view.

The newly formed strata will be consolidated by the application of heat; they may, perhaps, contract in bulk, and thus give space for new deposits, which will, in their turn, become similarly consolidated. But the surface of uniform temperature below the bed of the ocean cannot rise towards the earth's surface, without an increase in the temperature of all the beds of various rock on which it rests; and this increase must take place for a considerable depth. The consequence must be a gradual rise of the ancient bed of the ocean, and of all the deposits newly formed upon it. The shallowness of this altered ocean will, by exposing it to greater evaporation from the effect of the sun's heat, give increased force to the atmospheric causes still operating upon [214/215] inequalities of the solid surface, and tend more rapidly to fill up the depressions.

Possibly the conducting power of the heated rocks may be so slow, that its total effect may not be produced for centuries after the sea has given place to dry land; and we can conceive, that in such circumstances, — the force of the sun's rays from without, and the increasing heat from below, so consolidating the surface, that the land may again descend below the level of adjacent seas, even though its first bottom is still subject to the elevatory process. Thus, a series of shallow seas or large lakes might be formed; and these processes might even be repeated several times, before the full effect of the expansion from below had permanently raised the whole newly-formed land above the influence of the adjacent seas.

If the sea were originally much deeper, or, if in particular parts it were much deeper, as, for instance, ten or twenty miles, then a portion of the solid matter beneath its surface might, after the lapse of many ages, acquire a red, or even a melting heat, and the conversion into gases of some of the substances thus operated on, might give rise to earthquakes, or to subterraneous volcanoes.

On the other hand, as the high land gradually wears away, by the removal of a portion of its thickness, and [2215/16] as the cooling down of its surface takes place, its contraction might give rise to enormous rents. If these cracks penetrate to any great reservoirs of melted matter, such as appear to subsist beneath volcanoes, then they will be compressed by the contraction, and the melted matter will rise and fill the cracks, which, when cooled down, will become dykes.

If these rents do not reach the internal reservoir of melted matter, and if there exist in the neighbourhood any volcanic vents connected with it, the contraction of the upper strata may give rise to volcanic eruptions, through those vents, which might be driven by such a force to almost any height. These eruptions may themselves diminish the heat of the beds immediately above the melting cauldron from which they arise; for the conversion of some of the fluid substances into gases, on the removal of the enormous pressure, will rapidly abstract heat from the melted mass. As the removal of the upper surface of the high land will diminish its resistance to fracture, so the altered pressure arising from the removal of that weight, and its transfer to the bottom of the ocean, may determine the exit of the melted matter.

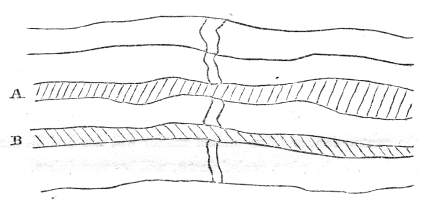

Other consequences might arise from the different fusibility of the various strata deposited in the bed of the ocean. Let us imagine, in the annexed wood cut, [216/217] the two beds, A and B, to melt at a much lower temperature than those between which they intervene.

It might happen, by the gradual rising of the isothermal surfaces, that one or both of those strata should be melted; and thus, supposing all the beds originally to have contained marine remains, we might, at a distant period, discover two interposed beds, without any trace of such remains, but presenting all the appearances of former fusion, resting on, separated by, and existing under, other beds of demonstrably marine formation.

If, during that former state of fusion, rents should have been formed through several of the strata, injection of the liquid matter might proceed from these melted beds, both upwards and downwards. If, on the contrary, older dykes had penetrated all the strata, it is possible to suppose such a degree of fusibility in the older dyke, or such chemical relation to the melted bed, that the portions of the dyke passing through that bed shall be obliterated, whilst those which traverse [217/218] the less fusible beds, protected from r.uch action, shall remain unaltered, as in the annexed cut.

Another consequence of this constant change in the position of the isothermal surfaces must be the development of thermo-electricity, which, acting on an immense scale, may determine the melting of some beds, or the combination of the melted masses of others, or cause the segregation of veins and crystals, in heated, though not fluid, portions of the strata exposed to its influence. Nor may the dykes themselves be without their use, either in keeping up the communication for the passage of electricity, if they are good conductors, — or in separating the groups of strata which produce it, if they are bad conductors. For the elucidation of this subject, it appears very important that experiment should be made on the effects of long-continued artificial heat in altering and obliterating the traces of organic remains existing in known rocks. It seems probable that by a well-planned series of such experiments, we might be enabled to [218/219] trace the gradually disappearing structure of animal remains existing in rocks subjected to fire, into marks which, without such aid, seem utterly distinct from that origin; and that we might thus establish new alphabets with which to attempt the deciphering of some of the older rocks.2 It appears, therefore, that from changes continually going on, by the destruction of forests, the filling up of seas, the wearing down of elevated lands, — the heat radiated from the earth's surface varies considerably at different periods. Inconsequence of this variation, and also in consequence of the covering up of the bottoms of seas, by the detritus of the land, the surfaces of equal temperature within the earth are continually changing their form, and exposing thick beds near the exterior to alterations of temperature. The expansion and contraction of these strata may form rents and veins, produce earthquakes, determine volcanic eruptions, elevate continents, and possibly raise mountain chains. The further consequences resulting from the working out of this theory would fill a volume, rather than a note. [219/220]

It may, however, be remarked, that whilst the principles on which it is founded are really existing causes, yet that the sufficiency of the theory for explaining all the phenomena cannot be admitted until it shall have been shown, that their power is fully adequate to produce all the observed effects.

14 December 2008