As Peter Galison points out in Einstein’s Clocks, his exploration of the relation of theories of relativity to late nineteenth-century attempts to synchronize clocks as a means of accurately mapping the world, such “mapping offered both symbolic and practical mastery over space. In the great land grab of the mid-nineteenth century, fixing positions was critical for trade, for military conquest, for laying railroads” (132). One result of this essential need to measure accurate distances lay in the merging of pure science and technology, for “finding longitude was part of the job description of French, British, and American astronomers, and they deployed every conceivable method to find it. But the quest to link the United States to the ‘well determined European observatories’ remained unfulfilled. Every expedition produced a new number.”

Only underwater electrical telegraph cables could break the impasse. Beginning in August 1857, missions had struggled against the North Atlantic to lay a telegraph line. Cables broke again and again; in June 1858, the fleet once more launched from Plymouth, England, with the vast cable. Just three days out at sea, a gale tore at the ships ceaselessly for nine days. Despite significant damage to one ship (and one sailor so terrified that he lost his reason), cablelaying continued. On 6 August 1858, the first signals finally passed through the cable, followed by a cable break and the cessation of submarine cabling during the Civil War. The American Civil War suspended attempts to connect Europe and North America by submarine cables. [133]

After war ended, plans to connect the two continents by submarine telegraphy revived. As Galison explains, “Pulling out from Valentia Island in southwestern Ireland in July 1865, the Great Eastern, a mammoth ship five times larger than any other, began hauling cable toward Newfoundland.” (133-34). All went well for more than a thousand miles, but suddenly the cable broke and sunk beneath the waves. The following year “another crew set out, this time aiming to run a much-improved cable from the tiny fishing hamlet at Heart’s Content, Newfoundland (on the eastern side of Trinity Bay, about ninety miles from St. John’s) to Valentia. This time: success. Communication started on 27 July 1866” (134).

The following illustrations that appeared in various numbers of The Illustrated London News, each “from a sketch by our [unidentified] special artist,” document the interest among the general public in a nineteenth-century technological feat equivalent in its time to the late twentieth-century ventures into space with rockets — and their initial failures.

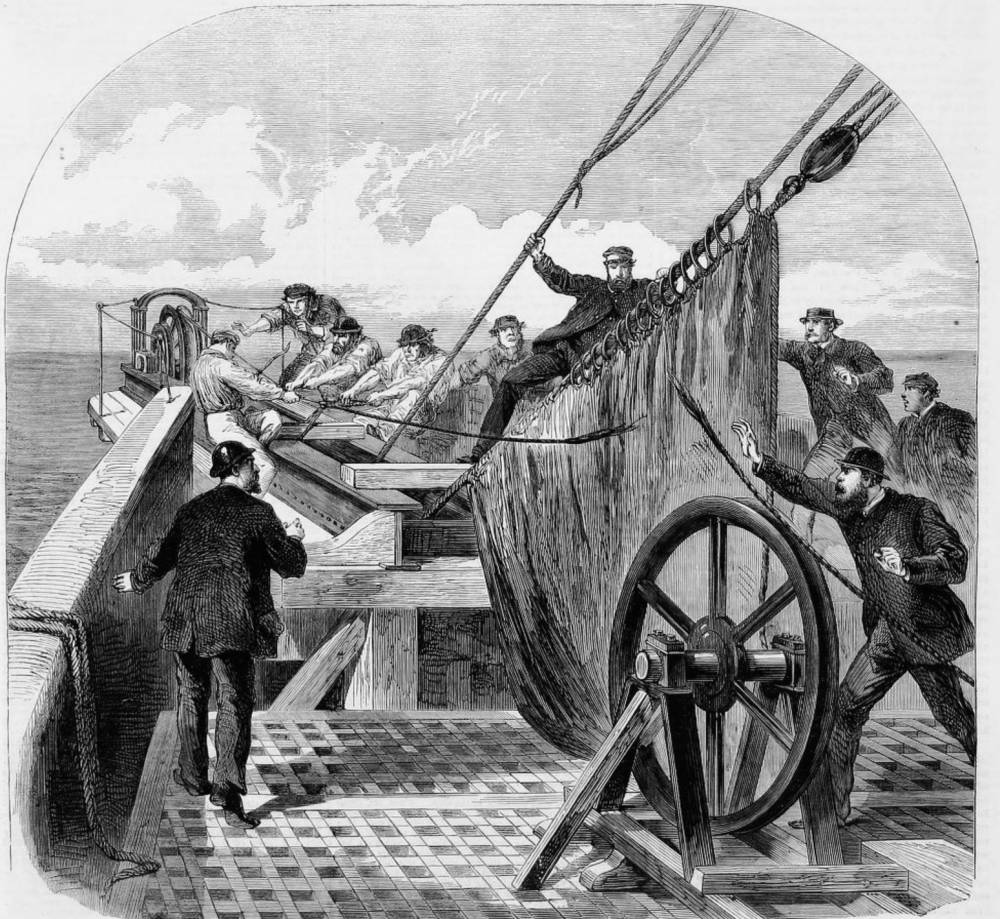

The Breaking of the Atlantic Telegraph Cable on Board the Great Eastern. “From a sketch by our special artist”. Source: 26 August 1865 issue of the Illustrated London News. Courtesy of the Internet Archive. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Left: Buoys and grapnels used in recovering the Atlantic Telegraph Cable of 1865.. Right: Preparing for the Final Attempt to Grapple the Lost Cable.

Left: Buoyed with Hope. Puck laments the Broken Girdle.. From the periodical Fun. Right: Preparing for the Final Attempt to Grapple the Lost Cable.

Left: The First Buoy Marking the Supposed Place where the Cable Broke. Right: The Second Buoy Marking the Exact Place where the Cable Was Grappled, Aug. 8.

The Paying-Out Machinery of the Great Eastern

You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and Hathi Digital Library Trust and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. — George P. Landow

Bibliography

“The Atlantic Telegraph Expedition.” Illustrated London news. 49 (2 September 1865): 224-25. Internet Archive online version. Web.

“Buoyed with Hope.” Fun. (2 September 1865): 155. The Hathi Digital Library Trust online version of a copy in the University of Minnesota library. Web. 25 June 2016.

“The Diary of the Cable.” Illustrated London news. 47 (26 August 1865) and 49 (22 September 1866). Internet Archive online version. Web.

Galison, Peter. Einstein’s Clocks, Poincaré’s Maps: Empires of Time. New York: W. W. Norton: 2003.

Last modified 3 December 2017