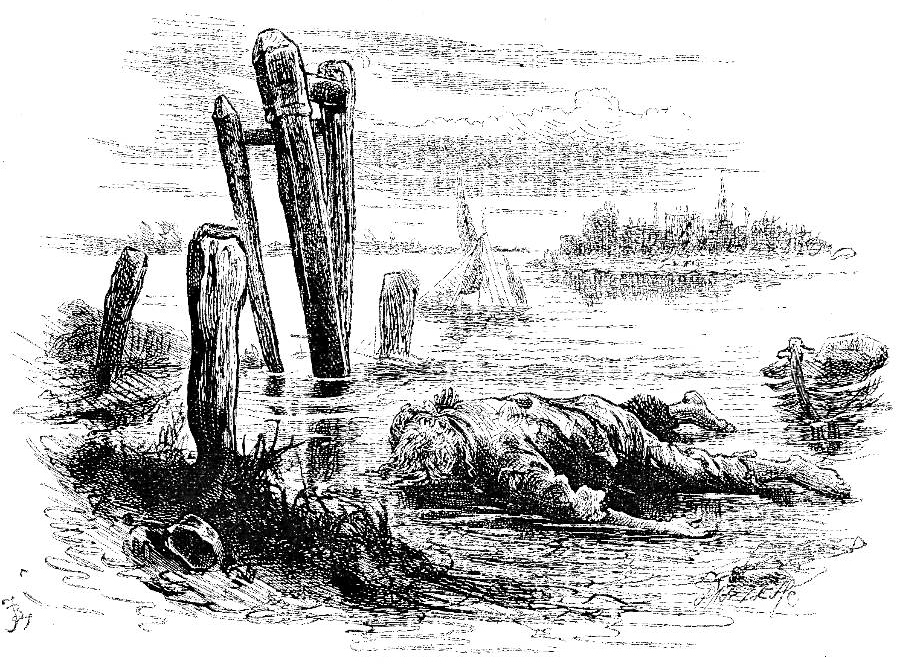

The body was washed ashore, some miles down river, a swollen disfigured mass (1876) is the caption used in the list of illustrations in the 1907 compilation of Household Edition illustrations, although this stunning tailpiece itself has no such caption in the 1876 British volume. The large-scale composite woodblock illustration is 9 cm by 12.3 cm (3 ½ by 4 ⅞ inches), vignetted, p. 24 in Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. A half-page wood-engraving for Chapter 12 in "Tales," in Dickens's Sketches by Boz, the thirteenth volume of the Household Edition, page 240 (uncaptioned). The grimly realistic tale was not illustrated by Dickens's original illustrator George Cruikshank in either the 1836 or 1839 editions of Sketches by Boz (John Macrone; Chapman & Hall), but is the subject of no less that three separate wood-engravings by Fred Barnard. The suicide image seems to be somewhat derivative, the pilings in particular suggesting that Barnard had studied similar illustrations by Phiz and Marcus Stone; all of these and the Barnard tailpiece may have influenced such later "found drowned" illustrations as Heath Robinson's Dead Castaway on the Beach in Kipling's Song of the English (1909).

Passage Illustrated: Found Drowned

He crept softly down the steep stone stairs that lead from the commencement of Waterloo Bridge, down to the water’s level. He crouched into a corner, and held his breath, as the patrol passed. Never did prisoner's heart throb with the hope of liberty and life half so eagerly as did that of the wretched man at the prospect of death. The watch passed close to him, but he remained unobserved; and after waiting till the sound of footsteps had died away in the distance, he cautiously descended, and stood beneath the gloomy arch that forms the landing-place from the river.

The tide was in, and the water flowed at his feet. The rain had ceased, the wind was lulled, and all was, for the moment, still and quiet — so quiet, that the slightest sound on the opposite bank, even the rippling of the water against the barges that were moored there, was distinctly audible to his ear. The stream stole languidly and sluggishly on. Strange and fantastic forms rose to the surface, and beckoned him to approach; dark gleaming eyes peered from the water, and seemed to mock his hesitation, while hollow murmurs from behind, urged him onwards. He retreated a few paces, took a short run, desperate leap, and plunged into the river.

Not five seconds had passed when he rose to the water’s surface — but what a change had taken place in that short time, in all his thoughts and feelings! Life — life in any form, poverty, misery, starvation — anything but death. He fought and struggled with the water that closed over his head, and screamed in agonies of terror. The curse of his own son rang in his ears. The shore — but one foot of dry ground — he could almost touch the step. One hand’s breadth nearer, and he was saved — but the tide bore him onward, under the dark arches of the bridge, and he sank to the bottom.

Again he rose, and struggled for life. For one instant — for one brief instant — the buildings on the river’s banks, the lights on the bridge through which the current had borne him, the black water, and the fast-flying clouds, were distinctly visible — once more he sunk, and once again he rose. Bright flames of fire shot up from earth to heaven, and reeled before his eyes, while the water thundered in his ears, and stunned him with its furious roar.

A week afterwards the body was washed ashore, some miles down the river, a swollen and disfigured mass. Unrecognised and unpitied, it was borne to the grave; and there it has long since mouldered away! — "Tales," chap. xii, 240.

Commentary

Once again, as the narrator of "The Drunkard's Death" declares, the events of the plot that lead to the climax at the end of the story are familiar ones, "of too frequent occurrence to be rare items in any man's experience" (p. 484). In this case, an alcoholic father neglects his saintly wife who eventually dies of a broken heart, drives his sons away from home, and exploits his daughter. The latter, in turn, eventually leaves him when one of her brothers, now a murderer who has returned to their slum apartment for refuge, is drunkenly betrayed by the father "into the hangman's hands" (p. 491). Once again, the primary purpose of this piece appears to be not its deliberately conventional account of the road to run — in this instance along the route later depicted in Cruikshank's The Bottle [eight illustrations, 1847] — but rather its presentation of an irrational state of mind. In particular, this irrational mental state is that of the reprobate father whose drunkenness is equated with madness. — Deborah A. Thomas, pp. 17-18.

Having actively sought his own death in the waters of the Thames at Waterloo Bridge, the drunkard ironically realizes that he wishes to live. But his resolution comes too late for him to save himself from drowning.

The protagonist has determined that he should die, alone and friendless, like Betty Higden in Our Mutual Friend, but he does not have the dignified death of the self-reliant old woman who has supported herself all her life and is not about to stoop to taking charity in her final days. In fact, by Providence (or sheer coincidence), Betty does not die alone as Lizzie Hexam finds her; no such providential piece of luck attends the death of the drunkard, Warden. Whereas the reader easily extends sympathy to the fiercely independent Betty as she is determined not to be a burden to the parish and die in a workhouse, Dickens and Barnard have to manipulate the reader through a sympathetic and sentimental portrayal of an incorrigible alcoholic whose addiction has led inevitably towards his suicide — as if he were one of the unfortunates in George Cruikshank's cautionary visual sequence The Drunkard's Children (1848). Dickens's including such a degenerate among his views of "Every-day People" implies that the author felt the problems caused by poverty and addiction were far more prevalent than his upper-middle-class readers would like to believe. The scene of the shore is a melancholy conclusion to a volume that began with social satire and acute observation of the London scene.

What exactly did the term "middle class" signify in London of the 1830s when young Dickens wrote a series of "sketches" to describe "Every-day Life and Every-day People"? Dickens's anxieties about his own place in this somewhat nebulous but growing constituent of English society are reflected in the range of young men who somehow exemplify le bourgeoisie Anglais. Hence, he begins with the local authority, the Beadle, and the parish council who traditionally elected this parochial figure. He includes in his description of middle-class types a small property owner, as in "Our Neighbour Next-door," and even a prosperous stock-brocker, the acme of the commercial class, Mr. Sempronius Gattleton of suburban Clapham Rise in "Mr. Joseph Porter," and even aspiring shop-people such as Jemima Evans and her beau ("Miss Evans and The Eagle"). Members of this class indulge in music, amateur theatricals, excursions, and even vacations. They seem much closer to modern, middle-class readers than, for example, the mixed bag of bourgeoisie who comprise Chaucer's pilgrims in The General Prologue to 'The Canterbury Tales'. They yearn for comfort, affluence, and family life, like the wealthy spinster Miss Lillerton, the timid bachelor Watkins Tottle, and the Kitterbells. But in "The Drunkard's Death" Dickens confronts what lies below the middle class, the under-class that his profligate father John very nearly joined once incarcerated in the Marshalsea Debtors' Prison.

Although to modern readers the final vision of the lower echelons of English society is depressing and thought-provoking, to young Charles Dickens just breaking into print and making his way up the class structure, the prospect of alcoholism, degeneracy, and an ignominious death in the waters of the Thames must have been terrifying. Certainly, in his later novels Dickens revisited such deaths in such scenes as "Yet the cold was merciful, for it was the cold night air and the rain that restored me from a swoon on the stones of the causeway" in Our Mutual Friend (Book Two, Chapter 13), "It's summut run down in the fog" in Our Mutual Friend (Book Three, Chapter 2), and The Bird of Prey brought down in Our Mutual Friend (Book One, Chapter 4). The composition, however, most closely resembles Phiz's Death of Quilp in the 16 January 1841 instalment of The Old Curiosity Shop, with the corpse lying washed up on the mudflats among some rotting pylons. However, whereas Phiz has an ominous sky on the horizon, Barnard here places London with its many church spires right, rear, giving both a context and a sense of alienation — the life of the metropolis goes on, despite society's failure in this particular, now lifeless figure who, unlike the corpse of Quilp, still looks very much human.

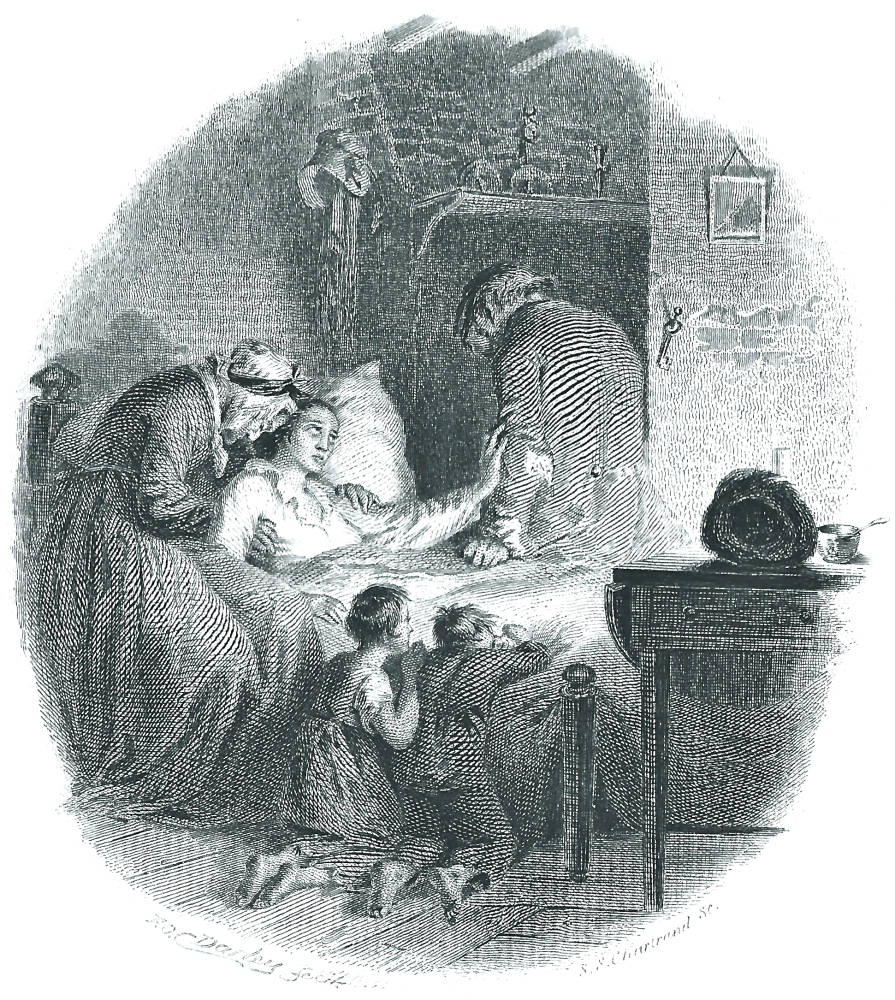

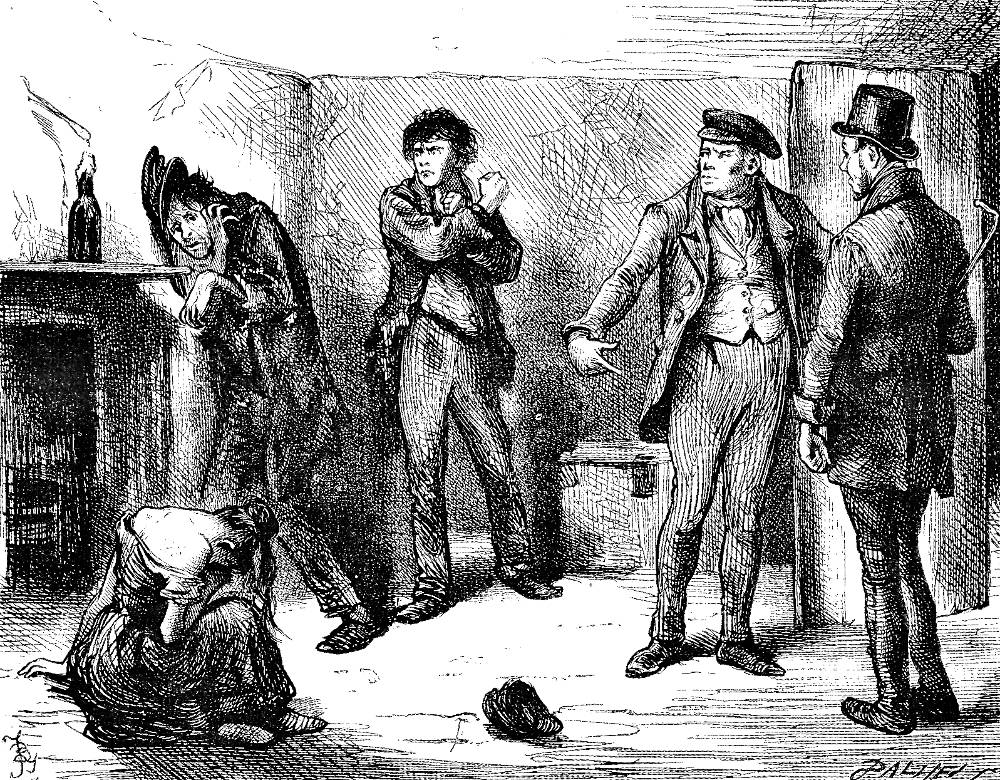

Other Nineteenth-century illustrations for "The Drunkard's Death"

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley's second frontispiece depicting the pathetic scene in which Mrs. Warden dies, probably of a combination of malnutrition and disease, The Drunkard's Death. (1864). Right: Barnard's moving portrait of the homeless alcoholic, Looks that he had long forgotten were fixed upon him once more; voices long since hushed in death sounded in his ears like the music of village bells. — "Tales," Ch. 12. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: The initial Barnard illustration, depicting the apprehension of the fugitive murderer, the drunkard's rebellious son, in He raised his manacled hands in a threatening attitude, fixed his eyes on his shrieking parent, and slowly left the room. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned images and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the images and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Bentley, Nicholas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens: Index. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z. The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. "The Drunkard's Death," Chapter 12 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Chapman and Hall, 1839; rpt., 1890. Pp. 368-76.

Dickens, Charles. "The Drunkard's Death," Chapter 12 in "Tales," Christmas Books and Sketches by Boz, Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: James R. Osgood, 1875 [rpt. of 1867 Ticknor and Fields edition]. Pp. 494-500.

Dickens, Charles. "The Drunkard's Death," Chapter 12 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. 22 vols. London: Chapman and Hall, 1876. Vol. XIII. Pp. 233-40.

Dickens, Charles. "The Drunkard's Death," Chapter 12 in "Tales," Sketches by Boz. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 1. Pp. 472-83.

Dickens, Charles. The Old Curiosity Shop. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). London: Chapman and Hall, 1841. Rpt., 1900 in The Authentic Edition.

Dickens, Charles. Sketches by Boz. Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People. Works ofCharles Dickens. Household Edition. 55 vols. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley. 2 vols. New York: Sheldon & Company, 1864.

Hawksley, Lucinda Dickens. Chapter 3, "Sketches by Boz." Dickens Bicentenary 1812-2012: Charles Dickens. San Rafael, California: Insight, 2011. Pp. 12-15.

Schlicke, Paul. "Sketches by Boz. Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999. Pp. 530-535.

"Sketches by Boz Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People — Thirty-four Illustrations by Fred Barnard." Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens, Being Eight Hundred and Sixty-six Drawings by Fred Barnard, Gordon Thomson, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), J. McL. Ralston, J. Mahoney, H. French, Charles Green,, E. G. Dalziel, A. B. Frost, F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes. London: Chapman and Hall, 1907.

Slater, Michael. Charles Dickens: A Life Defined by Writing. New Haven and London: Yale U. P., 2009.

Thomas, Deborah A. Dickens and the Short Story. Philadelphia: U. Pennsylvania Press, 1982.

Created 3 June 2017

Last updated 23 January 2025