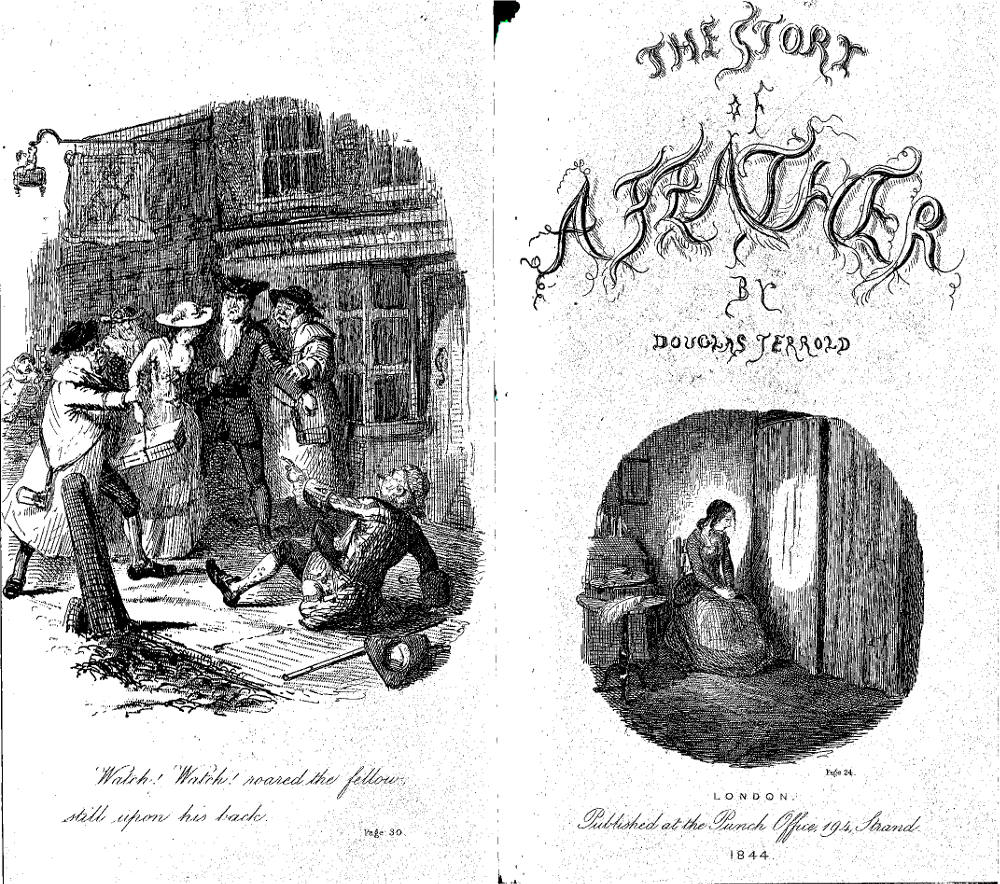

"Watch! Watch!" roared the fellow, still upon his back. — frontispiece; Patty Butler, the milliner, in her garret — Title-page vignette for Douglas Jerrold's The Story of a Feather (1844). Drawn by John Leech. Published at the offices of Punch; or, The London Charivari, 194 Strand. Vignettes: 12 cm high by 8.5 cm wide, and 6.5 cm high by 6.3 cm wide, respectively. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Passages Illustrated: Patty Butler & Julius Curlwell calls upon the Watch

"If you hav'n't a tongue, I'll see if you've lips!" exclaimed not the good angel of Patty Butler, — and the speaker threw his arms about the girl, who shrieked with misery and terror. Ere, however, the sound had died upon his ear, the ruffian had measured his length upon King George the Third's highway.

>Luke Knuckle, Mr. Flamingo's porter, had been sent to Patty to hurry her with her work. Arriving at the house but two or three minutes after her departure, he had followed closely on her steps, and was thus in a most advantageous situation for the proper application of his fist, at a most dramatic point of time.

Wach! watch!" roared the fellow, still upon his back; for with evidently a quick sense of the magnanimity of Britons, he felt the only means of escaping a second blow was to use nothing but his lungs.

What's the matter?" asked a watchman, who miraculously happened to be near the spot. [Chapter V, "Patty Butler finishes her work. — A word on London Garrets. — A Ruffian. — Patty in the Watch-house," pp. 29-30]

Jerrold's novella follows the mingled fortunes of the narrator (an ostrich feather) and a feather-dresser, young Patty Butler, in 1762. Both the frontispiece and title-page vignette involve the fifteen-year-old worker, who works out of her garret "in a pestilent and fever-breathing alley" (23) in order to support her sick mother. In the initial Leech illustration, Luke Knuckle, the feather-merchant's light-porter, has come to her rescue, but the well-dressed man harassing Patty, Julius Curlwell, accuses the pair of having robbed him.

In the title-page vignette, Jerrold describes the scene shortly prior to Patty's discovering that her mother has died in her sleep:

From earliest childhood, she was made to read the hardest words — want, poverty — in the iron book of daily life; and the early teaching had given to her face a look of years beyond her age. With her, daily misery had anticipated time.

And she sits, in that almost empty garret, a lovely sacred thing — a creature that redeems the evils and the wrongs of earth; and in her quiet suffering — in her devotion,constant to her heart as her heart's blood — gives best assurance of a future heaven. She sits, glorified by patient poverty. . . . [Chapter IV, "Patty Butler, the Feather-dresser. — Patty's Mother. — Mr. Lintley, the Apothecary," p. 24]

Commentary

The delicate elegance of the ostrich feather has traditionally been a symbol for luxurious extravagance. The history of dress has been the history of the elite with non-elite fashions being less well documented. The ostrich feather really took off with the fashionable elite in the 18th century and ostriches were heavily hunted. By the 19th century, the farming of ostriches allowed farmers to pluck the feathers instead of having to kill the birds. The trade peaked in the late 19th century before a decline and crash of the market at the onset of the First World War. [Stein]

Jerrold's feather was imported from the Cape of Good Hope in the eighteenth-century, but the story derives its nineteenth-century meaning from the continued use of ostrich feathers as fashion-accessories for ladies' hats. "Supporting this feathery fad was a small army of young, female feather dressers who prepared feathers from ostriches and other birds for use in hats, quills, pens, mattresses, and other goods" (Ancestry). One such young feather-dresser is Patty Butler, whose job as a feather-cleaner would likely lead to her dying young of tuberculosis, a job-related hazard.

Given its date of composition, it is possible that it constitutes one of the sources for Dickens's The Chimes (December 1844), although Dickens wrote the second of The Christmas Books. In 1867, Bradbury and Evans re-issued the story as the first illustrated edition, an octavo of 259 pages with full-page illustrations and in-text engravings by satirical Punch house-artist George Dumaurier.

Although the street scene from Chapter 5 has the theatricality of an etching by George Cruikshank, the portrait of the lonely feather-dresser in her garret is pure Leech — compare it to his drawing of seamstress Meggy Veck in Dickens's The Chimes from that same year: Richard and Margaret. Leech's sympathy with the economic underdog and his injecting pathos into a depiction of a working-class young woman compel the reader's identification with the protagonist.

Reference

"8 Jobs You Were Bon Too Late to Get." Ancestry. https://blogs.ancestry.com/cm/8-jobs-you-were-born-too-late-to-get/

Jerrold, Douglas. The Story of a Feather. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1844.

Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. "Ostrich feather trade — From fashion accessory to feather duster: the ostrich feather trade in London."London Metropolitan Archives. https://www.cityoflondon.gov.uk/things-to-do/london-metropolitan-archives/the-collections/Pages/ostrich-feather-trade.aspx.

Created 31 May 2019