he Victorians are often regarded as prudes, and it is widely believed that they took a negative view of sexuality. Many cultural assumptions surround this claim: intimacy before marriage was supposedly forbidden, women’s bodies were concealed in elaborate dresses, ignorance of ‘relations’ was thought to be widespread, female sexuality and nudity were apparently reviled and homosexuality was regarded as a mysterious and immoral aberration. For the Victorians, it is believed, sex existed for procreative rather than recreational purposes, and sensual pleasure was proscribed.

There is of course some evidence for this interpretation of the period, with theorists of the time denying the existence of the sexual instinct or describing it as a negative force. The foremost theorist of the time, William Acton, wrote at length of the damaging effects of male masturbation and (in)famously claimed in 1862 that ‘The majority of women (happily for them) are not very much troubled with sexual feeling of any kind’, and ‘seldom desire any sexual gratification’ for themselves (Functions 101–102). Others concurred and this view was carried into the twentieth century, with wider studies describing the Victorians’ stance on eroticism in Acton’s terms. The purported limitations of the Victorians’ sex lives are most clearly voiced in Michel Foucault’s influential (History of Sexuality (1976–2018). Foucault points to the difference between the open celebration of eroticism in previous centuries and what he sees as the passionless tedium of the Victorian age. According to Foucault, the libido played a limited part in the life of Victorians of all classes and was most constrained in the lives of the bourgeoisie, for whom there were only ‘monotonous nights’ (History).

It is a bold claim, and Foucault’s analysis, first published in 1976, probably had more impact than we might expect. It now seems as limited and misleading as Acton’s work of a century earlier. Viewing the Victorian age from the perspective of the so-called ‘sexual revolution’ of the twentieth century, Foucault only speaks disparagingly of what he saw as the Victorians’ lack of sexual interest. Yet there is much evidence to contradict his arguments, and common-sense suggests a series of questions which instantly reveal that the Victorians’ grim-lipped lack of a libido is a cultural myth. How could it be, for example, that eroticism was proscribed but families were typically large, with many couples producing more children than is currently the case in the western world? It could be argued that the largest families were those of the proletariat, crammed into the industrial cities, but it is also the case that the most ‘respectable’ families often reproduced on an unusual scale as well. How is it that men bathed nude at many British beaches – and were spied on by women? And how is it that prostitution flourished throughout the period, with pornography and salacious literature, exemplified by ‘Walter’s’ Secret Life (1888), produced on an industrial scale? All in all, it is clearly absurd that Victorian sexuality was purely a matter of ‘monotonous nights’. Foucault’s account is anything but the entire picture, and has been comprehensively challenged by critics such as Steven Marcus (1966) and Michael Mason (1994), and more recently by Ellen Bayuk Rosenman (2003).

Foucault is on firmer ground in his insistence on the notion of repression, arguing that the policing of sexuality became an aspect of bourgeois taste and culture, in which ‘twilight soon fell upon this bright day’ of honest openness, meaning that ‘Sexuality was carefully confined; it moved into the home. The conjugal family took custody of it … On the subject of sex, silence became the rule.’ (History). Again, Foucault overstates the case, but there is no doubt that the bourgeois emphasis on propriety, decorum and an authoritarian Christian morality invariably meant that sexual matters were rarely discussed in plain language outside the domain of pillow-talk.

But it was expressed, Foucault accepts and explains, in euphemism and code, enabling discussion of sex to develop into a discourse of its own. In verbal language a specialized vocabulary was developed to speak of eroticism and the body’s sexual workings. In the 1860s, for example, ‘horizontal refreshment’ signified intercourse for middle-class gentlemen, while ‘pridded’ (the equivalent to the modern ‘pricked’) was commonplace, if vulgar, slang. Elaborate codes and clues similarly acted as substitutes for the direct expression of sexual themes in Victorian art and literature, with a greater openness featuring in the Decadent, ‘Naughty Nineties’, especially in the hands of writers such as Thomas Hardy and George Gissing and in the work of neoclassical painters. As Rosenman makes clear, the Victorian ideology may have been ‘inhibiting’, but the reality ‘sheltered more inventive forms of eroticism than [the period] has been given credit for’ (2).

Of course, the treatment of libido in Victorian fiction and poetry has been explored in a vast body of criticism, and the same can be said of Victorian painting, sometimes invoking the insight that many images of the period were not only erotic but beyond the bounds of modern acceptability. Some neo-classical nudes, in particular, seem incompatible with attitudes of the twenty-first century and are occasionally regarded as transgressive or offensive; for example, J. W. Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) was recently taken down (2020) for a period by the curators of Manchester City Art Gallery because some spectators objected to the sexual dynamics of a painting which shows a man being enticed by naked adolescent girls. This is of course an anachronistic attitude which disregards the context and intention, seeing it in purely literal terms. However, it does refocus understanding of the period, making us see the considerable distance from the claim that the Victorians disliked sex to the position that the Victorians liked sex so much that they experimented with it, stretching its limits into the domain of what some would regard as perversion or paedophilia: hardly the imagery of ‘monotonous nights’.

J. W. Waterhouse’s Hylas and the Nymphs.

Rarely noticed, on the other hand, is the treatment of sexuality and sexual desire in Victorian illustration, with only the challenging art of Aubrey Beardsley at the end of the century forming an object of fascination. The development of this discourse as a whole is therefore a large and interesting field of inquiry, and one which requires a more extended treatment than it is possible to offer here. I make no claims of comprehensiveness. Rather, the aim of the following sections is to provide an introductory discussion of the main features of sexual themes as they appear in the Victorian graphic image, focusing on the diverse ways in which visual codes were deployed while also considering the many inconsistences in the mechanisms of control and censorship

.Propriety and Censorship in Early and Mid-Victorian Illustration

The Victorian middle classes of the early and middle part of the nineteenth century were bound by the rules of propriety, particularly as they were applied in the home. This point is important because most illustrated material was viewed by the parlour fireside where it was scrutinized by the householders, although it could also have been seen by those deemed in need of protection, notably children, female servants and inexperienced women. Sexual imagery was therefore strictly censored: it did not appear explicitly in family magazines (except as the result of a publisher’s error), nor did it openly feature in illustrated gift books. The situation was in any case relatively clear cut because the literature of the period did not publish any obviously salacious literature, and for the most part it was unlikely that illustrators could find an offensive subject to illustrate.

There were nevertheless significant exceptions to this rule, both serious and humorous. There are some occasions where bawdy material is presented in a humorous setting as a visual joke or pun. Perhaps the most amusing of these is Richard Doyle’s depiction of the figure apparently carrying the banner, in his second, celebrated version of the cover of Punch (1849). Placed within a mock-classical frieze, the character is usually described as a lampoon of Bacchus, with the face of Punch mounted on a bloated body, naked youths and maidens gambolling on either side, and one hand holding the shaft of a pole. Yet the character is not Bacchus but Priapus, and the upright supporting the banner is abruptly terminated before it connects with the heraldic device. In other words, Doyle represents Priapus holding a gigantic erection: a drollery that would have amused those who noticed it, but is half-concealed by playing on the limits of perception. Offered as piece of facetious humour, Doyle’s Priapus is a masculine joke, appealing to a male audience and defining the insolence of Punch’s politics, setting out to insult the world in an act of gross indecency; as M. H. Spielmann remarks, the cover is unashamedly ‘sporting and rollicking’, the journal’s ‘true spirit’ (47). In an age when the display of male genitals was proscribed and it was never permitted to show a penis in a state of arousal in any visual material, Doyle positions the magazine at the periphery of good taste. This was the mocking stance that the magazine wanted to project during its first, radical years under the editorship of Mark Lemon, although it is amusing to reflect that the very same cover was later to announce the urbane designs of George Du Maurier, John Tenniel and Phil May, and was continued until the wrapper was replaced in 1956.

Left: Richard Doyle’s celebrated front cover for Punch. Right: A detail of Priapus and his punning flag-staff, a version of ‘end of the pier’ obscenity.

.Doyle gets away with his drollery, but male genitals were far more problematic when they appeared in the more serious literary magazines of the period. One of the most provocative was Fred Sandys’s design for Once a Week, Danaë in the Brazen Chamber (1867), which was supposed to accompany a mildly erotic poem by Walter Swinburne. The engraving shows Danäe’s lover’s genitalia in tiny, diagrammatic detail in the tapestry to the left of the composition and are barely visible. Nevertheless, it is was enough to incur the disapproval of the publisher William Bradbury who, on seeing the offending parts, ‘playfully stamped his foot’ and declared he ‘would have no poultry on display’ in his magazine (Cooke, Illustrated Periodicals 81). Bradbury had already allowed – or did not see – Doyle’s gross obscenity hidden in plain sight on Punch’s wrapper, and yet he would not countenance such material appearing in the conservative pages of Once a Week, a literary family magazine and one radically different from the audacious London Charivari. His censorship was enough to keep Sandys’s image out of print for twenty years; it finally appeared in 1888 in the forward-looking setting of the Arts and Crafts magazine, The Century Guild Hobby Horse.

Sandys’s controversial design,

Danaë in the Brazen Chamber.

Bradbury’s unwillingness to risk causing offence seems coy and perhaps ridiculous, although it does seem to confirm the notion of mid-Victorian squeamishness in matters of a sexual nature. What it clearly demonstrates is the confusion which surrounded these issues. Male sexuality – even the sight of a naked penis – was not permitted in ‘respectable’ magazines, but the question of female eroticism is far more complicated, especially given Acton’s assertion that virtuous women had no sexual appetite. We would expect the representation of female sexuality to be as rigidly proscribed as that of men; but there were several occasions where artists honestly depict women’s desires while escaping censorship by exploring their erotic theme in a coded form. Danaë in the Brazen Chamber is an extraordinary example of this process at work: for while Bradbury disapproved of the lover’s genitalia, he made no mention of Danaë, who is depicted as a voluptuous figure in a state of arousal (as she contemplates the arrival of her lover, and is later impregnated in a shower of gold by Jupiter). Indeed, Bradbury’s incapacity to read the image is odd, given the proliferation of sexual signs: the facial expression, exposed throat, posture and half-revealed leg are at least provocative, and Sandys includes further visual clues which were weighted with significance for the contemporary viewer. The cascade of hair was especially erotic in an age when women’s coiffure was tied up except in the bedroom, and once released was taken as a signifier of sexual readiness. As Valentine Cunningham explains, for the Victorians a woman’s hair was a metonym for her pubic hair, and for ‘sexuality itself’ (Victorian Poetry) – a belief that would explain the de-sexing of classical nudes by depicting them entirely naked. The tussled bed on the right of the engraving confirms all of these readings, and the overall effect, with a woman presented for the delectation of the male gaze, is decidedly pornographic.

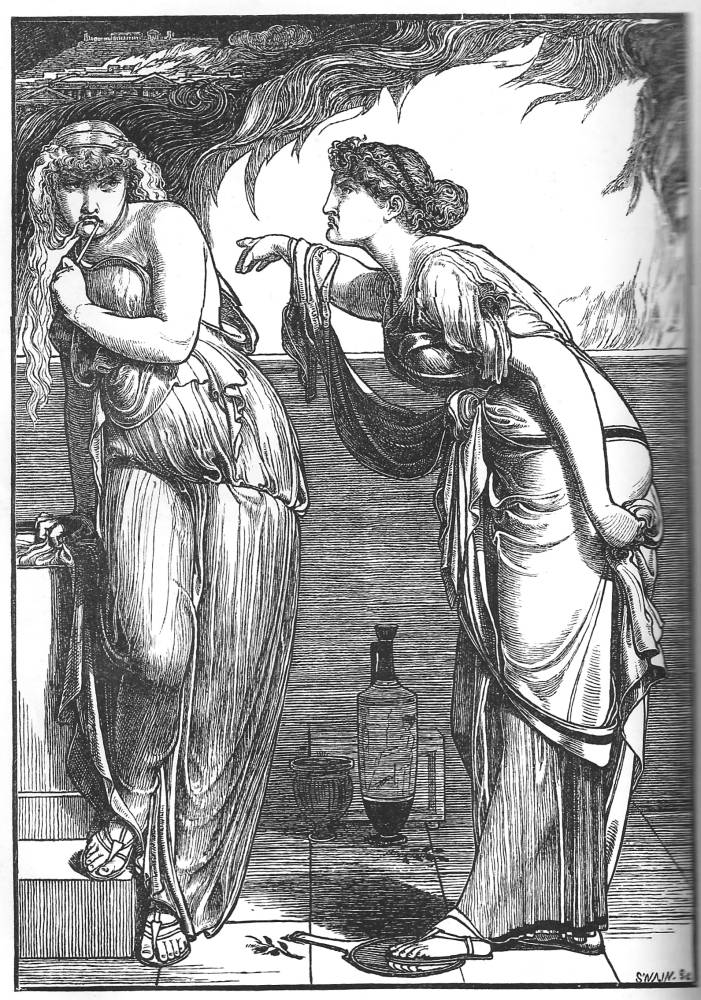

Nevertheless, Bradbury saw nothing offensive with this design because it was presented in a classical idiom. Sandys’s invocation of the trappings of an imagined past acts to legitimize the design and, as in the case of the pornographic or near-pornographic imagery of many neo-classical paintings, removes it from the accusation of having a real-life application or in any way pass comment on contemporary womanhood. As in works by Frederic Leighton, whose women are Roman or Greek beauties wrapped in diaphanous but revealing clothes, or nude, the charge of vulgarity is displaced and denied because the classical figure is supposed to be a sexless type of pure beauty: we have only to think of the veiled eroticism in late Victorian paintings such as Leighton’s Flaming June (1895) or Crenaia (1880) to see this process of justification at work. Viewing Sandys’s illustration in these terms, Bradbury linked it to high ideals of classical aestheticism, and were it not for the unacceptable detail would have almost certainly published it. Indeed, Bradbury and Evans published without comment Sandys’s other classical piece, Helen and Cassandra (Once a Week, 1866), which though suggestive of female sexuality – showing the two fleshly women in transparent robes – was deemed to be well within the limits of acceptability.

Left to right: (a) Sandys’s illustration of Helen and Cassandra; (b) Leighton’s Flaming June ; and (c), the same artist’s Crenaia.

These examples point to the curious inconsistences in early and mid-Victorian censorship and the ways in which artists such as Doyle and Sandys sought to circumvent them. They show it was possible to depict risqué material by presenting it in a coded form: it was acceptable to represent Priapus but not a modern character of the same type, and it was acceptable to show alluring semi-nudes from the domains of Greek Platonism, but not the sort of women who might appear in the illustrated pages of Trollope, who definitely had to keep their clothes on. Neo-classicism thus became a means of implying rather than directly showing, a visual language to denote the workings of sexuality.

Another variant – used in exactly in the same way as a means of both revealing and concealing – took the form of ethnic coding. Classicism enabled illustrators to legitimize sexual content, while imagery of other races allowed them to show eroticism in a distanced form. Sandys’s Cleopatra (The Cornhill Magazine, 1866), an illustration for another of Swinburne’s poems, is a prime example of this approach. The heroine, figured as a western woman, is the main subject, but in the background are a series of bare-breasted black woman. These sensual characters are shown semi-nude and are allowed to be shown in this condition because they are not white women: to do so would not be acceptable in a culture which endorsed racial theories with white Europeans as the superiors. But it was acceptable to project the sexual onto the foreign Other, the inferior alien whose behaviour or appearance was enticing but could not be judged according to the standards of middle-class Anglo-Saxons. Having used the figures to titillate, Sandys further insists on their inhuman status, as objects or curiosities, by reducing them to a single type, as if the women were part of a static frieze.

Left: Sandys’s Cleopatra; Right: Millais’s version of the same figure.

J. E. Millais similarly deploys what Lorraine Kooistra describes as an ‘entrenched stereotype’ (‘The Moxon Tennyson’) to depict his version of the Egyptian queen in his visualization of one of the characters in Tennyson’s ‘A Dream of Fair Women’. The illustration depicts her half-revealing and pointing to her breast, showing a nipple as she self-confidently addresses the reader and explains where the asp inflicted its bite. This act that would be normally regarded as highly offensive and provocative: impossible to show. However, in giving her a black skin – even though she is essentially a Caucasian in black-up – Millais gives her license to behave in a transgressive way. Once again, foreigners become surrogates, and are figured as an ethnic euphemism for a domain of experience that could not be presented directly (Cooke, The Moxon Tennyson 160–162); though regarded as inferior to the white English, blacks are deployed, in an act of staggering hypocrisy, to represent essential truths about the sexuality of the middle-class wives and daughters who may have glanced at the pages of Tennyson’s Poems. In this respect the treatment of erotic themes impinges upon and is influenced by racial attitudes and imperialism. But what of other ways of showing the libidinous?

Pre-Raphaelite Illustration and Heterosexuality

The ‘Pre-Raphaelite body’ has been explored at some length, notably by J. B. Bullen in his influential study of 1998. Bullen explores the Pre-Raphaelites’ concept of the human figure as a site of expression and as a locus of debates surrounding gender, male desire and female sexuality. Bullen explores notions of eroticism as they are embodied in painting, focusing especially on D. G. Rossetti’s treatment of this theme in the form of alluring women who are subject to the male gaze.

The critic points out that Rossetti’s approach is sometimes oblique and complicated, as in in Bocca Baciata (1859). On the other hand, several of the artist’s most elaborated paintings could be read as overstated celebrations of female sensuality and male longing. In (Venus Verticordia (1864–8), for instance, the semi-nude figure and outward facing gaze are near-pornographic in effect, presented in an image which attracts male perusal and objectifies women by reducing them to the level of sensuousness while half-disguising the subject in a neo-classical idiom. In Beata Beatrix (1864–8), conversely, the subject is female sexuality rather than the woman’s receptiveness to the male gaze, what Laura Mulvey famously formulates as ‘looked-at-ness’: though nominally a memento mori depicting Elizabeth Siddal as Beatrix as she expires, ‘rapt from Earth to Heaven’ (Surtees, 1, 94), it is essentially a picture of Rossetti’s memory of his wife in a state of arousal. Drawing upon the well-worn Elizabethan metaphor of sex and death, of dying and orgasm, Rossetti reveals an intimate moment. Intended for private patrons and never exhibited in the artist’s own lifetime, these paintings were designed for the perusal of their (male) purchasers, and were not for a wider audience. Such selectivity allowed the painter to explore proscribed areas of experience.

Left: Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix. Right: Millais’s Mariana.

When it came to illustration, however, Rossetti and the other Pre-Raphaelites were bound, like all illustrators, by the constraints of mass-publication. There is no possibility that images in the manner of Beata Beatrix could feature in any of the magazines or popular literature. Millais was likewise excluded, as already remarked, from direct expression: engaged in what Carol Jacobi has described as a ‘serious sexual poetry’ in his canvases, he produced suggestive paintings such as the Eve of St Agnes (1862) and Mariana (1850–51), the like of which could never appear in a printed volume. Nevertheless, all three of the original Pre-Raphaelites published sexualized imagery in a graphic form, notably in the Moxon Tennyson (1857) and again in Rossetti’s illustrations for his sister Christina’s Goblin Market (1862). Others associated with the movement, such as Simeon Solomon and Fred Sandys (as we have seen), were also contributors to the discourse,

In each case, censorship was deflected or evaded by depicting sexual subjects in the usual coded forms. The Pre-Raphaelites and their associates similarly conveyed their covert messages in types of symbolism which had a complex grammar and went beyond allusion to aesthetic prototypes or ethnic surrogates. They typically employed facial and physical signifiers, suggestive costumes and emblematic detail, often using apparently random objects or objects subsumed within a realistic surface as sexual signs. Some of these codes were established visual languages – particularly physiognomy and significant gesture – while others are a matter of personal association which can be read, as ‘symbolic realism’, within the schema of each design.

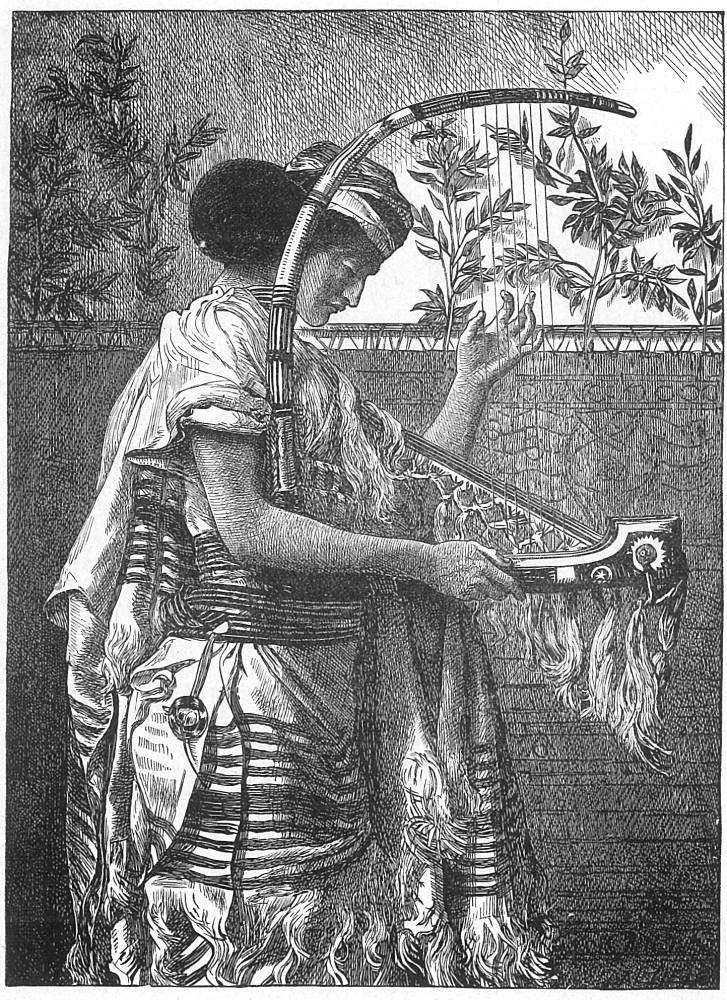

The practitioner of richest implication, predictably, was Rossetti, enabling him to visualize controversial material in which the main emphasis is on female experience and erotic pleasure, although he also visualizes male sexuality. His female characters’ state of mind is primarily realized in the scale and nature of their bodies, and in their poses and gestures. Rossetti’s management of an erotic pose is exemplified by his treatment of St Cecily, the first illustration for Tennyson’s ‘Palace of Art’ (1857). The image is supposed to depict a simple textual instruction: ‘Wound with white roses, slept St Cecily:/An angel look’d at her’ (Poems 118). What Rossetti shows, however, is at odds with the lines: instead of sleeping she is playing the organ; she has an arched back, an exposed throat and luxuriant hair; her face, with closed eyes, suggests arousal, and the angel is not looking at her, but kissing her. Tennyson writes the encounter as a spiritual one, but Rossetti converts it into an ecstatic moment. Employing what he believed to be the illustrator’s responsibility to ‘allegorize’ as he saw fit, he refigures the terms of the situation: sensual and suggestive rather than explicit or obscene, it could still be read in the domestic home. Invisible to children – and, more tellingly, invisible to the censoring hand of the publisher Moxon – its significance could barely be missed by mature viewers. He used exactly the same pose in reverse in Beata Beatrix, although it is interesting to note that the originator of Cecily’s attitude was Elizabeth Siddal, whose drawing of ‘St Cecily’ was adopted and modified by her partner.

Rossetti’s St Cecily.

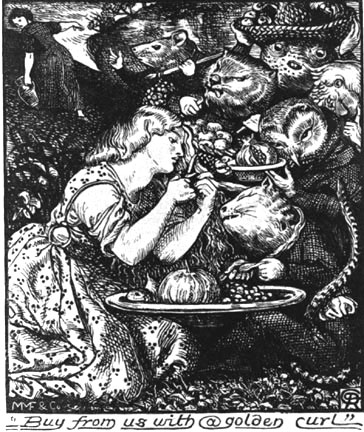

Rossetti’s interest in the sexualized pose is taken further in his pictorial frontispiece and title page for Christina Rossetti’s Goblin Market (1862). The two sisters, Laura and Lizzie, are depicted as voluptuous young women, practically bursting out of their dresses, and with fleshly elongated throats. The bodies are obvious signs of Rossetti’s reading of the title poem as an parable of innocence and experience, highlighting the idea that the sisters might be naïve but should be viewed, nevertheless, as mature women in a state of sexual preparedness.

Rossetti's title page for Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market.

This approach undermines the reading of the poem as a spiritual allegory and converts it into a reflection on female desire. Rossetti focuses this theme in the pictorial frontispiece, which shows the moment when Laura encounters the goblins. Represented as a monumental figure, her fleshliness extends the poem’s metaphors of eating: taking up on the consumption of ‘goblin pulp’ and ‘goblin dew’, Rossetti converts Laura into a piece of ripe fruit, the human equivalent of ‘plump unpecked cherries and apples’ which exist only to be consumed. The idea of women as fruit to be plucked is of course an ancient metaphor, and Rossetti highlights the notion that sexual experience is simply a part of nature: Laura is dressed in a costume decorated with what appear to be clusters of cherries, and her sexuality, the artist insists, is no more than a natural process. Always associated with Eve’s tempting apple, women such as Laura are made to be picked.

Yet he also stresses the dangers of female desire by depicting male sexuality as a predatory force. If Laura is to be eaten, it is the goblins who do the eating, metaphorically gobbling her up as if were indeed a piece of fruit. In particular, he highlights the notion of the violence of male eroticism by depicting the goblins not as men who look like animals but as animals who are dressed as men. Replacing the zoomorphic with the anthropomorphic, Rossetti identifies male desires as bestial, no different from the instincts of creatures. More especially, he personifies the goblins in terms of a significant bestiary in which each animal has a symbolic connotation. This is an example of Rossetti’s deployment of a semiotic which signified in its own time but is invisible today. As I explain in another essay:

To a modern reader the figures seem mere representations of some of the animals cited in the text; however, Rossetti carefully selects only those infused with specific emblematic meaning that would have been understood by the literate Victorian. These connotations are … derived from [the pseudo-science of] physiognomy, and can be read by linking them to books such as James Redfield’s bizarre but influential treatise of 1859, Comparative Physiognomy; Or, the Resemblances between Men and Animals. Read in relation to Redfield, we immediately see that the rat … is a sign of ‘cupidity and lust’; the cat is a symbol of smooth excess, and ‘relishes petting’; the parrot is full of mischief; and the fish is an emblem of unsatisfied desire, a creature for whom ‘Appetite is rendered rapacious [and is] never satisfied. [‘Interpreting Masculinity’ 143]

Rossetti's pictorial frontispiece of Christina Rossetti's Goblin Market.

Laura is thus confronted with the worst of male instincts: caught in a skein of interlocking lines which emanate like a net, her sexuality is aroused by the appetites of men-as-beasts. Never suggesting his message in an explicit way, Rossetti deploys a pre-existing code to strengthen the text’s emphasis on the depravity of Laura’s encounter with evil creatures.

He also exploits a wider symbolism, contained in tiny details of nature, to reinforce the meeting’s sensuality, what is essentially a sexual assault. The meeting of the genders is symbolized to the left of the composition by the intermingling of lilies (female purity) and bulrushes (a phallic symbol), and Laura kneels on a bed of mushrooms, which again suggests the invasive, phallic presence of the masculine. Likewise suggestive are the cat’s serpentine tail – another surrogate phallus and a reminder of Satan in the Garden of Eden – and the opened pomegranate, which recurs in his painting of Prosperine (1874), and has been read as a ‘cryptic image of the vagina’ (Piper 123).

Rossetti’s final, and most important symbol is the cutting of the ‘golden curl’ with a modern pair of scissors, which repeats the central motif of the watercolour, The Marriage of St George and Princess Sabra (1857). For the modern viewer, again, this is little more than quaintly discordant detail, but it is loaded with contemporary significance. As noted earlier, in Victorian culture a woman’s hair was regarded as a metonym for her pubic hair, and Laura’s cutting of her curls might thus be read as a matter, in Victorian parlance, of ‘breaking the virgin knot’. In giving a knot of her hair, Laura is symbolically giving her virginity.

All of these connotations are inscribed in Rossetti’s dream-like visualization of his sister’s nightmarish poem, Millais was similarly concerned with the deployment of codes and created his own semiotic of sexual meanings, exploring both male and female eroticism which functioned, once again, to convey its messages in an implicit rather than an explicit way. Millais’s graphic symbolism is modelled in his paintings. Jacobi has argued that some of the apparently innocuous items featuring in his canvases are phallic symbols. In her analysis of Millais’s The Bridesmaid (1851) she develops Tim Barringer’s Freudian notion of the shape of the sugar caster acting as a surrogate penis, anticipating future sexual experience; and she further identifies the threaded needle in the painted version of Mariana (1851) as a sign of the abandoned lover’s desire to be penetrated by Angelo.

Jacobi’s psychosexual interpretation is intriguing, and it could be the case that Millais uses the symbol of the pin in his second illustration for ‘The Talking Oak’ in Tennyson’s Poems (1857). The bride’s preparations are figured as a rustic epithalamion and her dresser features a pincushion, shown in minute detail, with pins sticking out of it. This could be no more than a naturalistic detail, but it could have more significance; is it, as Jacobi might argue, a sign of Olive’s sexual desire, in echo of Mariana’s? It does read in relation to Mariana and it might be a deliberate inclusion to suggest Olive’s longing. At the very least, the pins focus attention on the dress that will (probably) be removed with urgency on the lovers’ wedding night and perhaps Millais uses this small detail to distil the poem’s sexual themes. There is, particularly, a discernible erotic charge in the tree’s description of Olive’s kisses, directed at her lover’s carving of her name. She engages with the oak as a surrogate lover, and the personified tree responds as if it were her beau. The tree recounts the experience in suggestive terms:

“Her kisses were so close and kind,

That, trust me on my word,

Hard wood I am, and wrinkled rind,

But yet my sap was stirr’d:

And even into my inmost ring

A pleasure I discerned.” [Poems 249]

The sexual imagery employed here is surely intended to prefigure connubial eroticism (“sap was stirr’d,” “A pleasure I discerned”, “hard wood I am”), and Millais’s pins could well be the subtlest of suggestions, promoting on a tiny scale the author’s extended writing of desire in the weird manifestation of a talking oak. However, the image of the pins is figured as phallocentrism. Tennyson might be an exponent of the harmonies of marriage, but Millais subversively suggests that a wife’s duty is to be subordinate to the husband, who is armed with his phallus in the symbolic form of a pin.

Millais’s second illustration for Tennyson’s ‘The Talking Oak’, in his Poems..

We can see, in short, that Rossetti and Millais present a notion of intimate relationships in surprisingly misogynistic terms. In Rossetti’s illustrations women are fruit to be consumed, possessed and subjected to the power of male appetites; and in Millais’s they are regarded in terms of a penetrative, possibly painful, act. These ideas could barely be described as modern attitudes, but their inclusion in a coded form in mass publication suggests that they had a wide currency within the middle-class readership. Half-concealed in the objects of everyday life and scrupulously free of any obvious charge of indecency, the two artists’ versions of mid-Victorian sexuality is far from the stereotypical notion of the Victorians’ pallid repression.

The Pre-Raphaelites, Homosexuality and Androgyny

In an age when homosexuality was proscribed, the Pre-Raphaelites probed the boundaries of gender identity, offering a series of androgynous physical types. Rossetti and Holman Hunt present idealized female figures whose facial features partake of both genders, blending male signs such as a pronounced jawline with the signifiers of femininity, notably emphasising the eyes and endowing the characters with resplendent hair. Rossetti’s paintings of Jane Morris exemplify this approach: Proserpine (1874) and Astarte Syriaca (1877) are good examples, and so is the treatment of the woman in Holman Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd (1851) and in his version of the tormented heroine of Tennyson’s ‘The Lady of Shalott’ (1857). This hybrid characterization became the defining image of Pre-Raphaelite womanhood, and was carried forward in practitioners of the second generation, particularly Fred Sandys and Simeon Solomon.

Left to right: (a) Rossetti’s Proserpine; (b) the same artist’s Astarte Syriaca; and (c) Holman Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd.

The philosophical basis of this gender-blend is complicated. In general terms, it was a matter of exploring new concepts of beauty, physical and spiritual. In Rossetti’s art the fusion of male and female features was emblematic of the pursuit of spiritual union in which love was contemplated as a perfect state or merging of the souls, and gender – or difference – became insignificant; the fluidity of the masculine and feminine is reconciled into a new harmony. Simeon Solomon likewise dissolves the differences in his paintings of androgynous figures, some of them, were it not for their costumes, being impossible to ascribe a definite gender. In Sandys’s painting, on the other hand, the depiction of masculine-looking women acts to suggest their personalities: put crudely, his is an art of mannish women with the character traits more conventionally associated with men.

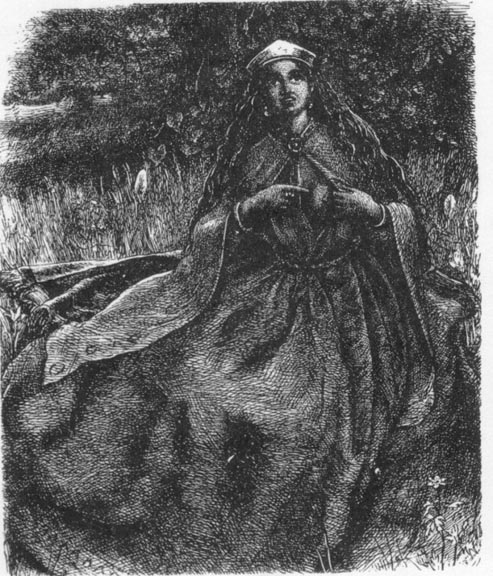

So how is this complex discourse reflected in Pre-Raphaelite illustration? To some extent, the imagery of the painting is transferred to the graphic art. Rossetti’s robust women reappear in his illustrations for Goblin Market (1862) and Sandys’s masculine-looking females are featured in his magazine designs, sometimes in the form of femme fatales – as in Rosamund in Once a Week (1861) – and sometimes as self-willed and petulant girls, such as the waiting lover in the image for Christina Rossetti’s If (The Churchman’s Family Magazine, 1866).

Left: Sandys’s Rosamund, Queen of the Lombards. Right: Sandys’s If he would come today.

More complex and unusual, however, is the illustration of men who are ascribed a female appearance and, by implication, the female characteristics, as they were conventionally understood, of sensitivity and introspection. If Pre-Raphaelite women partake of male traits, then the equation is applied the other way, refiguring orthodox notions of masculinity by depicting men as having the ‘softer virtues’ of the ‘weaker sex’, allowing them, as it were, to be dreamers, a feminized types who are free of the constraints of machismo. This approach is pursued by Holman Hunt in his designs for the Moxon Tennyson, and is especially marked in his treatment of the narrator in the first illustration for ‘The Arabian Nights’ as he floats downstream. As I explain elsewhere:

The elongated curvaceous legs are feminine rather than masculine signifiers, and the roundness of the figure is expanded in the form of the impossibly curved boat in which he reclines; endowed with small feet placed in delicate shoes like slippers, he melodramatically places his hand over his face and seems more like a middle-class lady reclining on a chaise longue than an adventurer. [Cooke, Moxon Tennyson 169]

In place of the notion of the male as a thrusting, dynamic force, as defined by Samuel Smiles in Self-Help (1859), the illustration emphasises the character’s dreaminess, endowing him with the introspective qualities that contemporary audiences regarded as signs of female thoughtfulness. Such an approach runs the risk of being accused of feminizing men in a period when the term ‘effeminacy’ was equivalent to the charge of homosexuality, and it is surprising that the design was passed over without negative comment. Its approach is typical, nevertheless, of the ways in which the Pre-Raphaelites contested conventional expectations by confounding ideas of the fixedness of gender identities.

Holman Hunt’s first illustration for ‘The

Arabian Nights’, in Tennyson’s Poems.

This project is taken much further in the art of Simeon Solomon, a gay artist whose life was blighted by his prosecution for committing homosexual offences. Solomon’s work, in the form of paintings and illustrations, is practically gender-neutral, creating a series of androgynous figures in which the characteristics of male and female intermingle. Practising in the idiom of second stage Pre-Raphaelitism and heavily influenced by Rossetti, Solomon suggests male strength in the strong features of his females, and female sensitivity in the faces of his men, extending that hybridity to include a free mixing of types of gestures.

An example of Solomon’s androgyny,

Sappho and Erinna in a Garden at Mytilene.

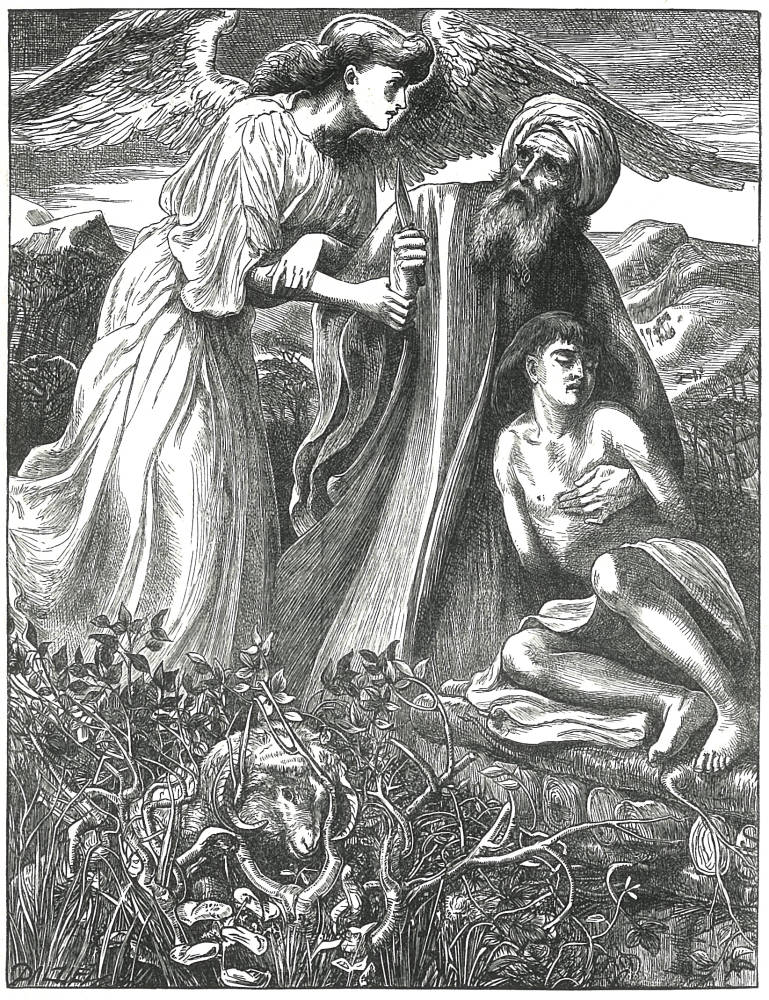

His conflating of distinctions is given illustrative form in his sensitive and distinguished work for the Dalziels’ Bible Gallery, which was published in the November of 1880; others featured in Art Pictures from the Old Testament [1894], although both publications contained work from the 1860s.

In Abraham and the Three Angels, the supernatural beings could be either gender; they are described in Genesis as ‘three men’ and ‘strangers’, but Solomon stresses the kindness of their benign message – that Abraham will have a son by Sarah – by giving them the softened faces of women, combining those feminized portraits with understated and reassuring gestures. This tenderness is carried through all of Solomon’s Biblical cast, typically in the form of the male children and angels. In each case he endows them with a distinctive sense of inwardness which sometimes seems at odds with the bellicosity of the Old Testament tales and refigures them as characters engaged in poetic moments in which conflict, especially the conflict between men and women, is replaced with a new sense of harmonious integration and psychological oneness.

Three illustrations by Solomon: (a) Abraham and the Three Angels. (b) Abraham’s Sacrifice. (c) Hosannah!

His approach was not appreciated in his own time, however. Responding to his paintings in terms which could also have been applied to his illustrations in black and white, many Victorian critics regarded Solomon’s androgyny as an aberration, the embodiment of what was considered to be his immoral or degenerate sexuality. In the words of William Richmond, his art was often in the ‘artificial and neurotic vein … of debased Roman art’ (qtd. Goldman 56). Few observers of our own time would agree, and in some ways his illustrations seem remarkably modern in their pursuit of a more liberal notion of identity while depicting high drama in a sympathetic and compassionate way.

Eroticism and Obscenity in Illustration of the Nineties

The coding of eroticism continued into the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and beyond, with art and literature negotiating a series of symbolic surrogates to explore libidinal experience. At the end of period there were nevertheless a number of cultural influences which encouraged a greater openness. One was the availability of pornography in the form of literary material such as Walter’s Secret Life (1888), a lurid text Ellen Rosenman describes as the ‘most frank, explicit, extended document of erotic self-fashioning in nineteenth century Britain’ (167), though much of the interest in looking at private acts was enshrined in photography.

In turn, these developments were fuelled by the more liberal attitudes of intellectual elites that crystallized in the aesthetics of the Decadence. Heavily influenced by French exemplars, the British fin-de-siècle was characterized by transgressive writing in which sexuality was positioned within a complex nexus of existential despair, fatigue, anxieties relating to the notion of degeneracy and a realization that art could only be artifice and was unable to capture the essentials of life. Oscar Wilde, Ernest Dowson and Arthur Symons exemplified this body of interests, and all contributed to the discourse of sex and sexuality, exploring eroticism in terms which vary between the febrile and the perverse.

It was in book art for minority audiences, however, that these world-weary attitudes found the clearest expression in the work of Aubrey Beardsley. Beardsley challenged censorship of the printed image and was calculatedly provocative in his representation of sexual mores. Always controversial and regarded as one of the enfants terribles of the period, his approach oscillated between the coded and the explicit, though in every case he deflected the negative charge of pornography.

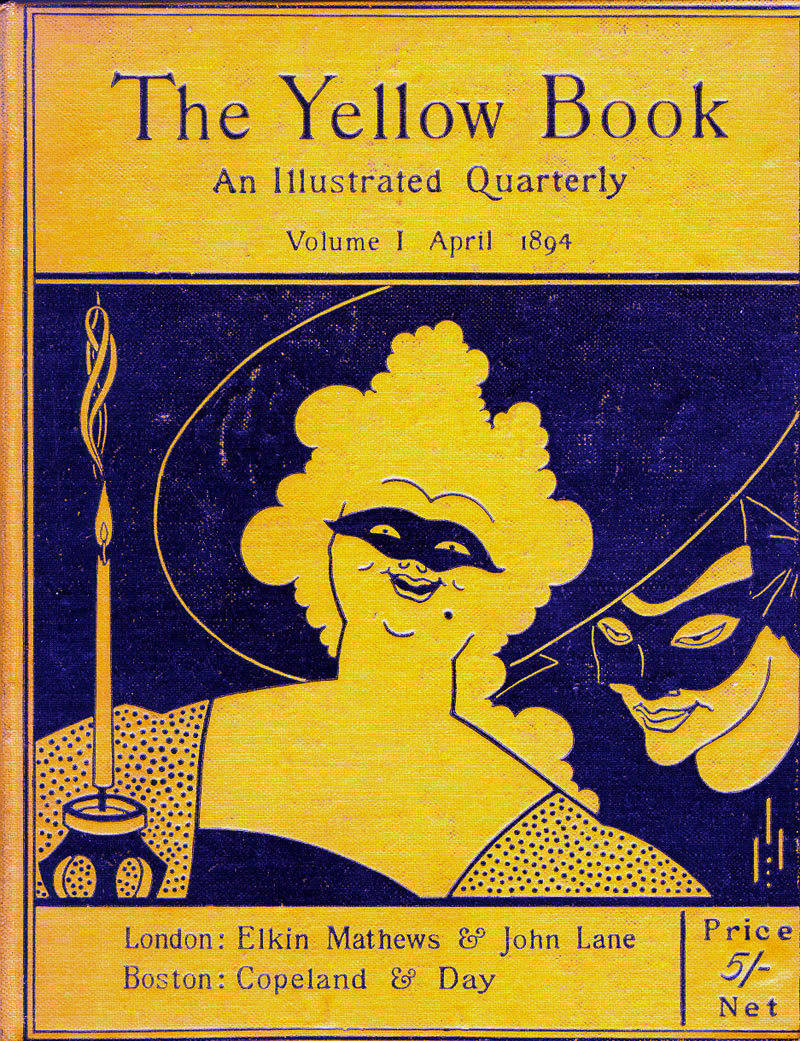

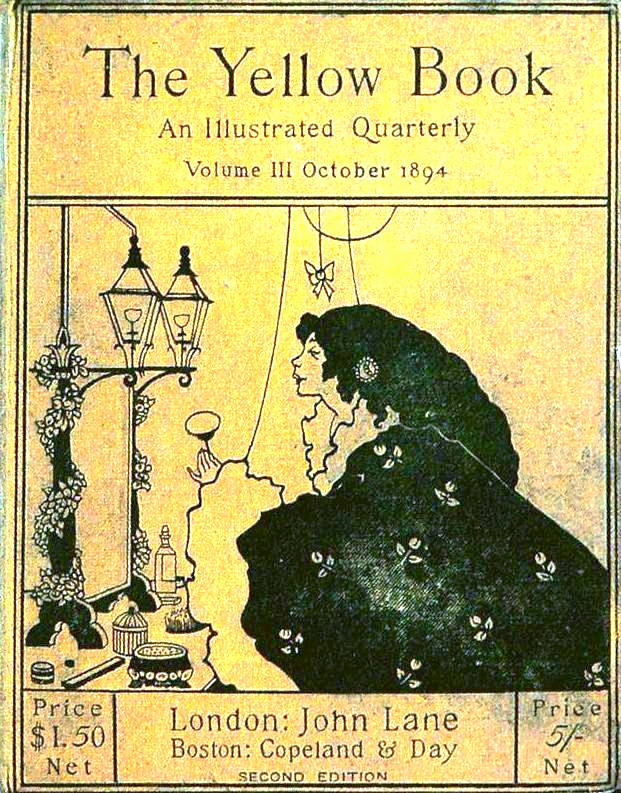

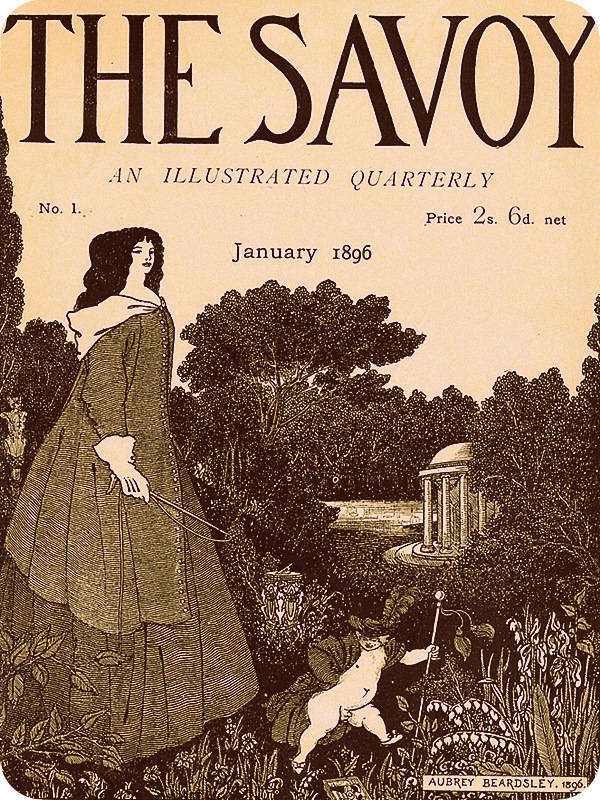

Some of his work was suggestive, making connections between the educated consumer, the Victorian counter-culture of prostitution and the underworld of homosexuality. In a curious echo of Doyle’s obscenity on the front cover of Punch, he published outré work in his wrapper designs for The Yellow Book and The Savoy, in each case presenting the perceptions of the flâneur whose leisure time is spent in experiences of hedonistic and perhaps depraved excess. The opening number of The Yellow Book (April 1894) depicts masked figures, one grotesque and one sinister, engaged in a masque, while the third (October 1894) depicts an upper-class prostitute at her toilette, an image revisited within its pages. Both designs are provocative, but Beardsley is careful to make them ambiguous rather than explicit.

Three provocative cover designs by Beardsley: (a) the opening number of The Yellow Book; (b) Volume three; and {c) The cover for number one of The Savoy.

He only hints at depravity in his dream-like images for the front cover of The Savoy, particularly in the wrapper for the first issue (January 1896), where he combines an elegant lady with a naked and pot-bellied incubus with his penis on display; the woman is endowed with a whip and is taking the creature for a walk as if she were exercising a dog. In this treatment the incubus becomes the woman’s sex-slave, kept in order by flagellation. It is salacious, vulgar material, almost a school-boy joke, and Beardsley mocks the viewer’s perceptions by alluding to classical imagery in the form of a temple in the background. Having already distanced the image from the accusation of contemporaneity by drawing it in a cartoon-style, he implies that it is really a classical scene, converting the incubus into a sort of cherub, occupying a world where nudity was celebrated rather than sexualized.

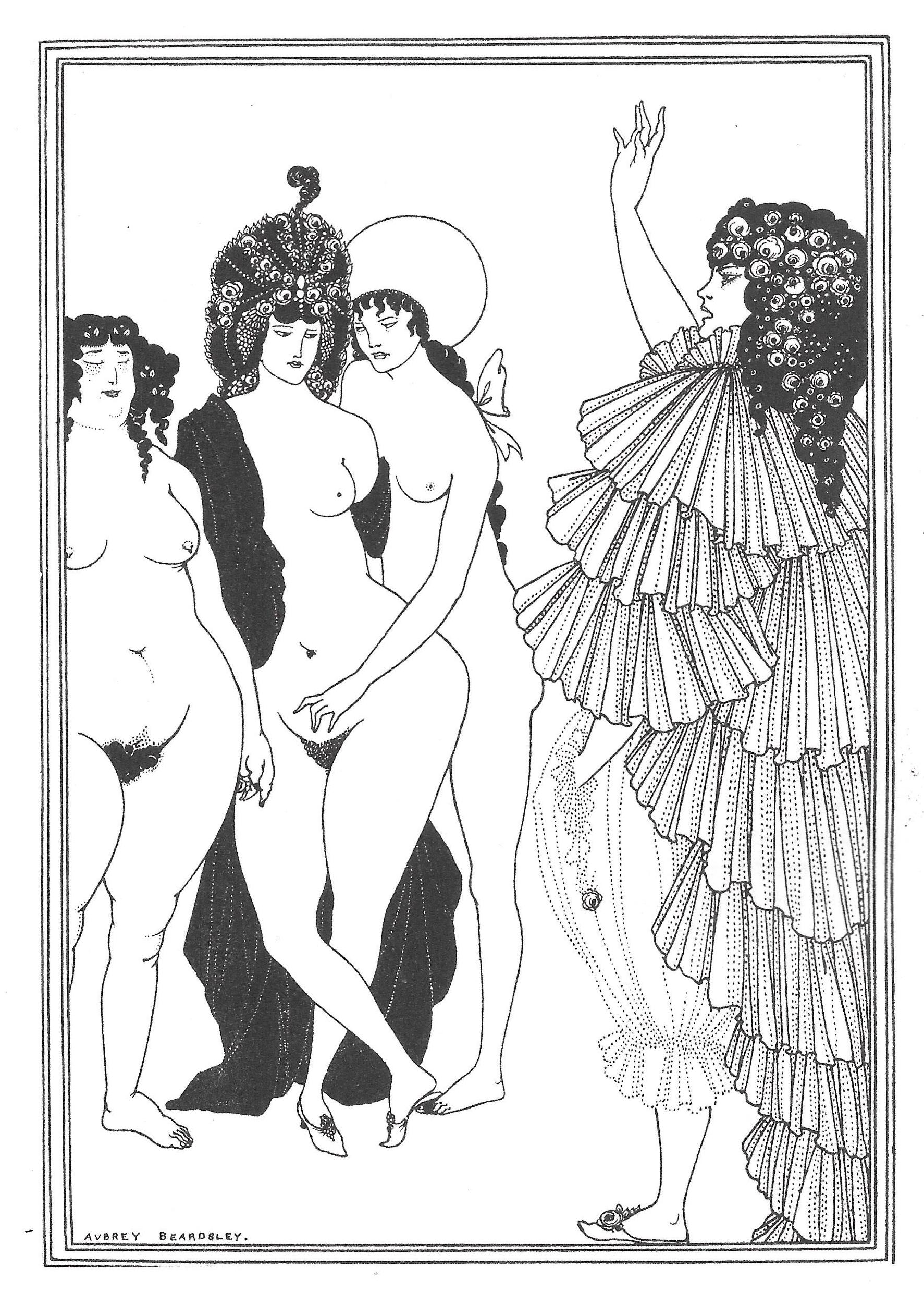

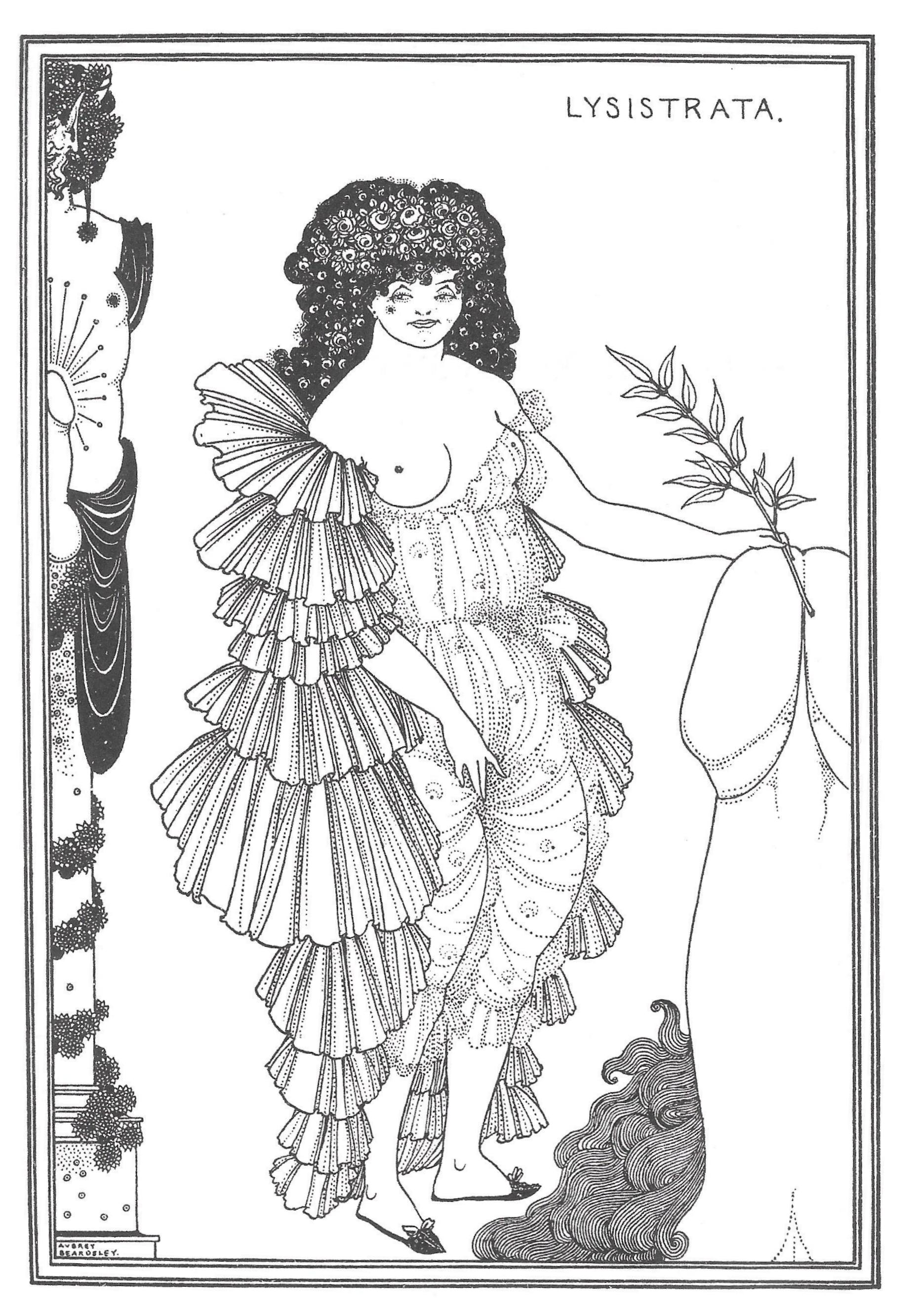

This satirical stance typifies Beardsley’s sophisticated subversion of conventional codes to create an ironic effect. His deployment of what is best described as ‘mock-classicism’ is exemplified by his celebrated designs for his version of Greek sex-comedy, The Lysistrata of Aristophanes (1896). Privately published in an edition of a 100 by Leonard Smithers and only available to subscribers, Lysistrata was the perfect vehicle for the representation of sexual material, allowing the artist to serve the text and stretch the bounds of propriety.

Dressing his characters in classical costumes in accordance with the play’s historical period, and therein providing justification for obscenities, Beardsley foregrounds the themes of withholding sex and sexual frustration, in each case presenting an imagery of nude figures with pubic hair and gigantic penises that would have been entirely unacceptable in earlier publications and was still unacceptable in the Nineties except in this sort of private edition. Lysistra haranguing the Athenian Women takes the main situation – Lysistrata’s persuading of the women to withhold sexual privileges until the Peloponnesian War were brought to a close – but highlights its eroticism by showing the characters naked with hirsuite pubis. Lysistra shielding her coynte from a gigantic penis and Cinesias entreating Myrrhina to coition are likewise confrontational images protected by the assertion that they are illustrating literary material.

Three pieces of comic-strip eroticism by Beardsley: (a) Lysistra haranguing the Athenian Women ; (b) Lysistra shielding her coynte; (c) Cinesias entreating Myrrhina to coition.

Beardsley is at his most obviously obscene in his representation of the men with huge erections. The examination of the herald and the Lacedaemonian Ambassadors exemplify his approach, but here again he invokes the justification of context: the men have erections because they are frustrated.

Two more obscene jokes by Beardsley: Left: The examination of the herald ; Right: The Lacedaemonian Ambassadors .

He also deflects the charge of obscenity by framing the imagery in terms of another series of visual codes. The figures are by turns idealized or grotesque, but they are always comedic, near cartoons which undermine the notion that they depict ‘real’ sexuality by offering ridiculous exaggerations. Should we be shocked, or just laugh at their vulgarity? Beardsley teasingly questions the viewer’s responses, an approach many observers have found unsettling. In the judgment of Edward Lucie Smith, his illustrations are an ‘act of aggression again society and against the spectator’, who is ‘forced into a kind of complicity or driven to reacting violently’ (141). A final line of ironic defence is created by offering a parody of ancient Greek vase-paintings, which routinely depicted erotic scenes, especially figures with gigantic phalluses. In these designs the tone is celebratory, but Beardsley re-presents the imagery as farce.

Wrapping his eroticism in a series of jokes, a sort of visual satire to match the text’s humorous critique of sexual politics, Beardsley thus offers a visual interpretation of Lysistrata which veers between the shocking and the amusing. In an age when such material is only presented in an allusive or suggestive way, Beardsley’s designs are the pictorial equivalent of Walter’s Secret Life, a narrative that writes the narrator’s many encounters in a knowing and sometimes amusing way. Both texts represent the final destination of Victorian sensibilities surrounding the taboos of eroticism.

Victorian Sexuality and Graphic Art

Beardsley’s imagery for Lysistrata is the extreme point of the depiction of sexuality in Victorian illustration, side-stepping the systems of censorship which were applied to mainstream books and magazines. It is, in this sense, atypical, designed for the taste of a minority and still regarded with suspicion when it is opened up to a wider audience. The Lysistrata designs have been displayed on several occasions in the modern age, and even today they are usually presented with a warning that those likely to be offended should not enter the exhibition space.

When we look at illustration as a whole, however, it is clear that the scope for sexual expression was generally far narrower than it was in either painting or literature. Censored by editors and limited by its role as a mass medium operating principally in a domestic milieu, illustration as an art-form was compelled, as we have seen, to disguise its sexual themes in codes, jokes, irony, visual puns and the pretence of offering designs in a classical garb. Reduced to the level of sub-text, the content could only be carried in implication, projecting a symbolic language that the sophisticated would see while not corrupting the innocent or self-denying.

The final word is from Sandys, whose image of Danaë in the Brazen Chamber is emblematic of the inconsistencies in attitudes. Sandys, we have seen, worked hard to present an illustration of female arousal in the context of a family journal – Once a Week – only to be confounded by the publisher’s unexpected objection to the least offensive element in the design. But he had earlier published in the same periodical Once more upon the organ play (1861), an engraving to illustrate a poem by Julia Goddard. The illustration shows a male body raised in death throes – or orgasm, visualizing the Elizabethan notion of sexual climax as ‘dying’. On this occasion, Bradbury again failed to see the double entendre, nor did he notice how once more playing ‘on the organ’ had erotic (and distinctly vulgar) undertones. Sandys published his work with impunity, appealing to the code-breakers of his age. Many illustrators occupied the same, risqué pitch as they sought to encompass all aspects of human experience.

Related Material

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Aristophanes. Lysistrata. London: Smithers, 1896.

Art Pictures from the Old Testament. London: Dalton [1894].

The Century Guild Hobby Horse, 1888.

The Churchman’s Family Magazine, 1866.

The Cornhill Magazine, 1860–70.

Dalziels’ Bible Gallery. London: Routledge, 1881.

Once a Week, 1860 –1870.

Punch, 1849–1955.

Rossetti, Christina.Goblin Market.London: Macmillan, 1862.

The Savoy, 1896

Tennyson, Alfred. Poems. London: Moxon, 1857.

The Yellow Book, 1894

’Walter’. My Secret Life. London: 1888.

Secondary Material

Acton, William.The Functions and Disorders of the Reproductive Organs in Childhood, Youth, Adult Age and Advanced Life Considered in Their Physiological, Social and Moral Relations. London: Churchill, 1862.

Bullen, J. B. The Pre-Raphaelite Body: Fear and Desire in Painting, Poetry, and Criticism. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1988.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s. Pinner: Private Libraries Association, 2010.

Cooke, Simon. ‘Interpreting Masculinity: Pre-Raphaelite Illustration and the Works of Tennyson, Christina Rossetti and Trollope’. Pre-Raphaelite Masculinities. Eds. Amelia Yeates & Serena Trowbridge. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014. 127–150.

Cooke, Simon.The Moxon Tennyson: A Landmark in Victorian Illustration. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2021.

Cunningham, Valentine.Victorian Poetry Now. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, online edition.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. Rpt. London: Penguin, 1992.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians Aldershot: Scolar, 1996, 2004.

Jacobi, Carol. ‘Sugar, Salt and Curdled Milk: Millais and the Synthetic Subject’, Tate Paper 18.

Kooistra, Lorraine Janzen. ‘The Moxon Tennyson as Textual Event: 1857, Wood-Engraving, and Visual Culture.’ Branch (January 2013). On-line periodical.

Lucie-Smith, Edward. Sexuality in Western Art.London: Thames & Hudson, 1972.

Marcus, Steven.The Other Victorians: A Study of Sexuality and Pornography in Mid Nineteenth Century England. New York: Random House, 1981.

Mason, Michael.The Making of Victorian Sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Mulvey, Laura. ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’. Screen 16:3 (Autumn 1975): 6–18.

Piper, David. The History of Art from the French Revolution. New York: Random House, 1981.

Rosenman, Ellen Bayuk. Unauthorized Pleasures: Accounts of Victorian Erotic Experience. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003.

Spielmann, M. H. The History of Punch. London: Cassell, 1895.

Created 1 March 2021

Last modified 24 April 2025