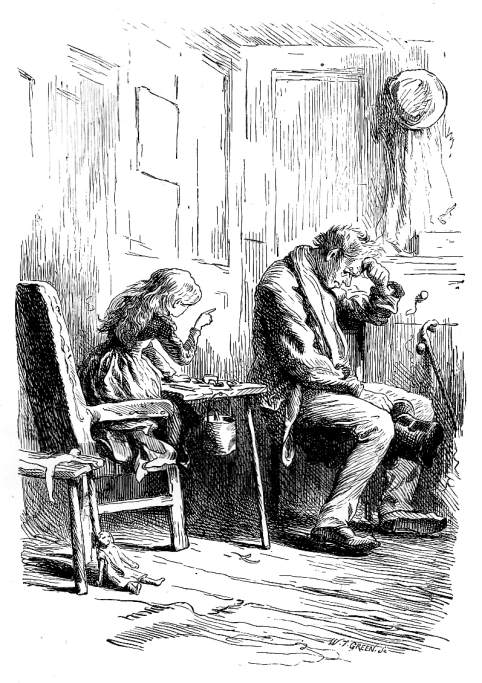

The Person of the House and the Bad Child

Marcus Stone

Wood engraving by W. T. Green

13.6 cm high x 9.6 cm wide

Dickens's Our Mutual Friend, Chapter Two of the second book, "Still Educational" [This part of the novel originally appeared in periodical form in October 1864.]

This 30 September 1864 illustration depends for its effectiveness upon the startling contrast between the accusatory finger of the doll's dress-maker, Jenny Wren, and hand to the forehead, suggestive of introspection and anguish of the alcoholic parent. [continue below]

Image scan and text by Philip V. Allingham

You may use this image without prior permission as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned it and (2) link to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.

The 30 September 1864 illustration "The Person of the House and the Bad Child" in chapter 2 ("Still Educational") of the second book depends for its effectiveness upon the startling contrast between the accusatory finger of the doll's dress-maker, Jenny Wren, and hand to the forehead, suggestive of introspection and anguish of the alcoholic parent. Stone has brilliantly conveyed the drive and determination of the child and the slovenly retreat from adult responsibility by her forward-leaning posture and the angle of the legs of the miscreant. [Continued below]

As Steig notes in Dickens and Phiz, the wood-engraving eschews caricature even in a subject so fitting for such a treatment, and no longer relies on emblem and allusion as the steel engravings of Phiz and Cruikshank did; rather, as we see in this Stone wood-engraving, subtle details of posture and clothing have entirely replaced the older method of the illustrator's commenting on his material, through such details of physical setting as material objects, notably paintings and posters. A "New Man of the Sixties," Stone like others among the new generation of illustrators (notably John Millais, Fred Walker, Fred Barnard) realized that the new medium of the wood engraving was most useful in delineating character. Dickens, too, must be credited with exploiting the possibilities of the new medium, as his "letterings" or captions for Stone's illustrations consistently suggest a focus on character over setting. For the sixth instalment of the novel, Dickens himself proposed this scene ("The Dolls Dress Maker") as a subject for the October number to Stone in a letter of 7 July 1864; he gave Stone the precise title in a letter of 26 August 1864: "The person of the house and the bad child" (Vol. 10: 421). Compare Stone's treatment of this subject to the rather more vigorous depiction of delinquent father and chastising daughter in Eytinge's study for the Harper's New Monthly Magazine serialisation of the novel.

The contrapposto modeling of the figure of the "Bad Child" renders him the sympathetic focus of attention in Stone's illustration, his agony over his addiction and its consequences implied by his posture, and attempt to retreat from his lively little daughter and her pointed chastisement of his recent binge. In contrast, the hard-working dolls'-dressmaker, interrupted in the midst of her labours, performing surgery on a doll's dress, is Eytinge's focus; by positioning her to the right (i. e., stage left), Eytinge has blocked the insentient parent's retreat, were he capable of so much action. A subtle detail in Stone's treatment is the walking cane beside the Bad Child, implying that he, too, has a disability. His top-hat he holds between his knees, as his whole pose betokens shame and self-loathing. On the wall, an adult-sized female's bonnet and shawl hang on the peg in Stone's plate to imply the daughter's grown up status as bread-winner and money-minder ("The Person of the House"), whereas in Eytinge's version the short garment on the peg is better suited to Jenny Wren's diminutive form, and perhaps implies that it is unjust and unnatural that one so young should have to assume such authority. Rather more melodramatic than strictly realist, Eytinge's "The Person of the House and the Bad Child" depicts the errant parent as a sad clown who is barely able to raise his hands as described in the text, is so stupefied that he sits inert, with his shabby great coat and disreputable hat still covering his ill-kempt hair, as if unable to exert himself even in so minor a matter as removing these garments indoors. His mask-like face and lifeless eyes he directs away from her and at the floor. Stone's requiring the reader to supply the earnest child's facial expression as she looks up from her work-table is one of the illustration's admirable subtleties.

References

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901.

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Il. Sol Eytinge, Jr. Illustrated Household Edition. Boston and New York: Lee & Shepard; Charles T. Dillingham, 1870. Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Il. James Mahoney. Household Edition. London and New York: Chapman & Hall; Harper Bros., 1875. Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Storey, Graham, ed. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Vol. 10 (1862-64). The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1998. Storey, Graham, ed. The Letters of Charles Dickens. Vol. 11 (1865-67). The Pilgrim Edition. Oxford: Clarendon, 1999.Victorian

Web

Our Mutual

Friend

Illus-

tration

Marcus

Stone

Next

Last modified 21 December 2010