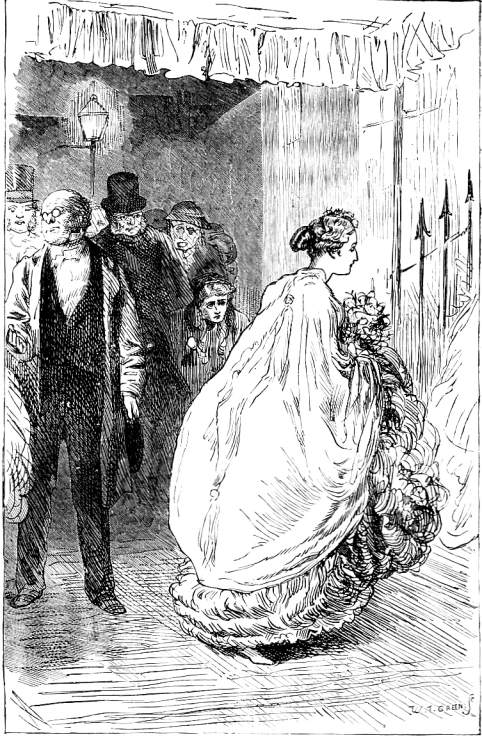

Trying on for the Doll's Dressmaker

Marcus Stone

Wood engraving by W. T. Green

14.5 cm high x 9.4 cm wide

Stone's illustration for Book 3,"A Long Lane," Chapter 2, "A Respected Friend in a New Aspect," reverts to the oddly sympathetic figure of the child-adult, the doll's dressmaker, Jenny Wren, who has great ladies unwittingly "try on" the dresses that she is making in the latest society fashion for her dolls. In other words, in a neat bit of class reversal, she exploits the rich and powerful as an extension of her art, using ladies of fashion for her models as the novelist uses people of his acquaintance as the raw material for his characterisations. As Jenny Wren explains to Riah just after they have crossed London Bridge and seen some of her wares in the window of a toy-shop,

[See below for commentary and passage illustrated.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Commentary

Although the passage describes Jenny Wren's impressions of the appearance and fashions of society ladies "at a Park, or a Show, or a Fete," the illustration embodies a specific flashback, presumably to Lady Belinda Whitrose as she left the social function.

as they were going along, Jenny twisted her venerable friend aside to a brilliantly-lighted toy-shop window, and said: 'Now look at 'em! All my work!'

This referred to a dazzling semicircle of dolls in all the colours of the rainbow, who were dressed for presentation at court, for going to balls, for going out driving, for going out on horseback, for going out walking, for going to get married, for going to help other dolls to get married, for all the gay events of life.

'Pretty, pretty, pretty!' said the old man with a clap of his hands. 'Most elegant taste!'

'Glad you like 'em,' returned Miss Wren, loftily. 'But the fun is, godmother, how I make the great ladies try my dresses on. Though it's the hardest part of my business, and would be, even if my back were not bad and my legs queer.'

He looked at her as not understanding what she said.

'Bless you, godmother,' said Miss Wren, 'I have to scud about town at all hours. If it was only sitting at my bench, cutting out and sewing, it would be comparatively easy work; but it's the trying-on by the great ladies that takes it out of me.'

'How, the trying-on?' asked Riah.

'What a mooney godmother you are, after all!' returned Miss Wren. 'Look here. There's a Drawing Room, or a grand day in the Park, or a Show, or a Fete, or what you like. Very well. I squeeze among the crowd, and I look about me. When I see a great lady very suitable for my business, I say "You'll do, my dear!' and I take particular notice of her, and run home and cut her out and baste her. Then another day, I come scudding back again to try on, and then I take particular notice of her again. Sometimes she plainly seems to say, 'How that little creature is staring!' and sometimes likes it and sometimes don't, but much more often yes than no. All the time I am only saying to myself, "I must hollow out a bit here; I must slope away there;" and I am making a perfect slave of her, with making her try on my doll's dress. Evening parties are severer work for me, because there's only a doorway for a full view, and what with hobbling among the wheels of the carriages and the legs of the horses, I fully expect to be run over some night. However, there I have 'em, just the same. When they go bobbing into the hall from the carriage, and catch a glimpse of my little physiognomy poked out from behind a policeman's cape in the rain, I dare say they think I am wondering and admiring with all my eyes and heart, but they little think they're only working for my dolls! There was Lady Belinda Whitrose. I made her do double duty in one night. I said when she came out of the carriage, "You'll do, my dear!" and I ran straight home and cut her out and basted her. Back I came again, and waited behind the men that called the carriages. Very bad night too. At last, "Lady Belinda Whitrose's carriage! Lady Belinda Whitrose coming down!" And I made her try on — oh! and take pains about it too — before she got seated. That's Lady Belinda hanging up by the waist, much too near the gaslight for a wax one, with her toes turned in.' [378-379]

The picture relies for its effectiveness upon the sharp contrast between the observant child (centre) in the midst of an odd assortment of strangely disfigured people on the pavement (left rear) and the gorgeous dress which dominates the woodcut, contrasting the strangely distorted faces that form the chorus in the background, which, if the gas lamp is any indication, is the London street outside.

Charles Dickens's "Originals" and Jenny Wren's Dresses

Famously Dickens took such real-life figures as the chiropodist Mrs. Jane Seymour Hill (his neighbour at Devonshire Terrace) and the Romantic essayist and editor Leigh Hunt as the bases for Miss Mowcher and Harold Skimpole, in David Copperfield and Bleak House respectively. As in the case of another David Copperfield character, Tommy Traddles (based on Thomas Noon Talfourd, the playwright and jurist), such a transmutation was often benign in intention — although Mrs. Hill did not receive the character of Miss Mowcher as a compliment. Mr. Micawber in David Copperfield is a marvellous contribution to those enduring statements that writers from across the ages have made about human nature — expansive, theatrical, flamboyant, larger than life — a literary construct based closely on the novelist's own father. Not so delightful is the character based on the novelist's mother, Mrs. Micawber. Presumably, Lady Belinda Whitrose never recognised that her dress her served as the basis for a doll's outfit in a toyshop window, and therefore was neither as chagrined nor as affronted as Leigh Hunt and Jane Seymour Hill.

Dickens's youthful protagonists, on the other hand, are generally derived directly from literary sources such as the novels of Fielding, Smollett, and Sir Walter Scott. Sometimes Dickens even based a character merely on a real- life personage's peculiar name — for example, Dr. Marley, a mere acquaintance in the autumn of 1843, unconsciously loaned his name to Jacob Marley, Scrooge's deceased partner and initial ghostly visitor in A Christmas Carol.

References

Dickens, Charles. Our Mutual Friend. Il. Marcus Stone. Volume 14 of the Authentic Edition. London: Chapman and Hall; New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1901.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Victorian

Web

Our Mutual

Friend

Illus-

tration

Marcus

Stone

Next

Last modified 16 June 2011