n 1859 Elizabeth Gaskell published "Lois the Witch" in Dickens's All the Year Round. It would be republished in Lois the Witch and Other Tales in 1861, and tells the tragic story of an orphaned Warwickshire girl, eighteen-year-old Lois Barclay, who is sent out to Salem in the American colony of Massachusetts Bay in the seventeenth century, to live with her cousins. At the end of the novella we learn that she had had a romantic connection in England with the dashing Ralph Lucy, whose upper-class family had objected to the match. In Salem, her cousin Manasseh, a deeply disturbed young man, comes to believe he is destined to marry her. There is also a possible relationship with Father Nolan, a kindly local minister. But the central concern here is not romantic; rather, it is with the events leading up to Lois's death for the crime of witchcraft, a charge she denies, and one that Gaskell makes clear is completely unjust.

"The witch no. 1 / J.E. Baker" (1892), print from a lithograph (Library of Congress prints and photographs divison, reproduction no. LC-DIG-ppmsca-09402).

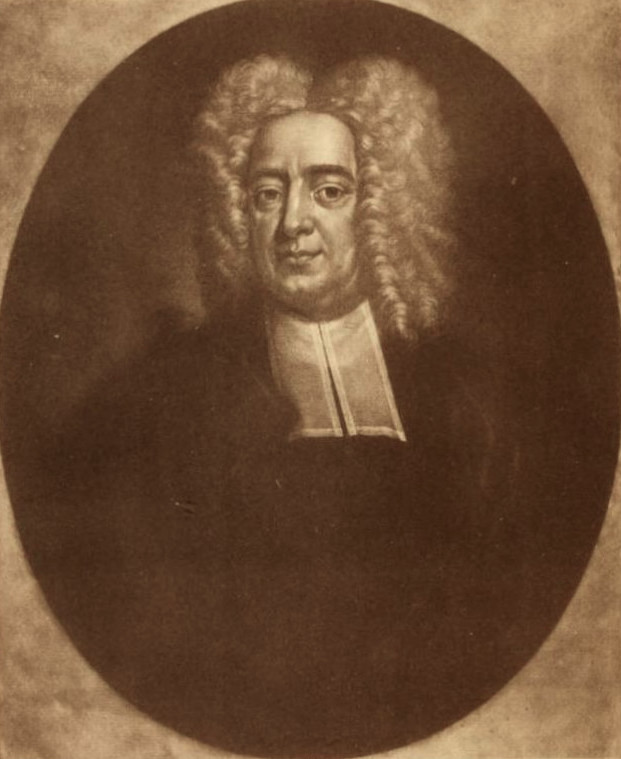

Why did Gaskell chose to tell a story of witchcraft in Salem, drawing on events there in 1692-93? After all, a British woman, Mary Oliver, had been burned to death for witchcraft in Norwich in 1659. Gaskell's recourse to the American episode remains part of a larger question: how did the Salem trials come to dominate literary narratives about this topic? But that is too big a question to examine here. Suffice it to say that Gaskell was indeed fascinated by them, to the extent that in 1847 she published in Howitt's Journal under the pseudonym of "Cotton Mather Mills." Mather was the New England clergyman who defended the American trials, and who has, rightly or wrongly, gone down in history as the chief villain of the piece.

Gaskell's likely, but not certain, source for the episode was the American Charles Upham, by far the most influential teller of Salem's witchcraft story. In his own 1867 book on Salem "witchcraft," Upham would create or codify various myths about the Salem trials, views that extend into some scholarly books today, as well as to non-specialist audiences. His study, a combination of good history and perpetuated or created myths, is no doubt the most influential book on the Salem witch trials ever written. Even people who have never read him, but who have heard of his accounts from other sources, have been influenced by his narrative. True, his 1867 work was not available to Gaskell at the time she was writing her own story, but he had already published a less widely known book on the subject in 1831: Lectures on Witchcraft Comprising a History of the Delusion in Salem in 1692. There were of course other possible sources for Gaskell's adoption of the pseudonym "Cotton Mather," and Gaskell may perhaps have found Salem's story elsewhere. Nevertheless, Upham seems the most likely source both for the name "Cotton Mather," and her own subsequent witchcraft story — especially since this earlier work was reviewed by Harriet Martineau in the Monthly Repository, a Unitarian journal, in 1832. Martineau's long, thoughtful review appeared in the very year in which the young Elizabeth married William Gaskell, the assistant minister at Cross Street Unitarian Chapel in Manchester (see Styles 84, n. 2). It does what any good review should do, making clear the relevance of the book to its readers, and concluding: "it is true that the times are so far ameliorated that the plague of superstition cannot ravage society as formerly. But society is not yet safe..." (555).

Title page of Upham's Lectures.

In Upham's telling, the Salem Witch Trials began with an Indian woman, Tituba, now the servant/slave of the pastor, the Reverend Samuel Parris, telling stories to his impressionable children. The result was bizarre behavior by the girls that elided into the accusation that witchcraft was being practised on them. Picking and choosing from the events in Salem, Gaskell moves the focus to Lois, the newcomer to the affected household. On her voyage, Lois had been consigned to the safe hands of Captain Holdernesse, a kindly man who had nevertheless told Lois enough of her prospective destination, the new world, to frighten her. Now, her destiny is set when she is taken to her relatives' home, and receives a cold reception from her aunt, Grace Hickson, who denies having received any letter from England about her coming. The situation is eased only through the intervention of her cousin Manasseh, a troubled young man in his twenties. His problems soon become clear, but on this particular occasion he is fixated on a book he is reading, breaking away from it only long enough to instruct his mother to be more hospitable. At this point, when Captain Holdernesse leaves her in this alien household, Lois loses the only warmth and comfort she had experienced since leaving England.

Gaskell makes no mention of witchcraft yet, but Upham's narrative seems to hover over this opening. As in Upham's account, in "Lois the Witch" there have been disputes over the colony's charter, and an Indian woman has been installed in a clergyman's household. In fact, Gaskell introduces two Indian women in her narrative One, in Lois's new home, is named Nattee, and she, like Tituba in Upham's Salem story, scares the girls of the household (in this case, Lois and her cousins Faith and Prudence) with "wild stories ... of the wizards of her race," taking a "strange unconscious pleasure in her power over her hearers — young girls of the oppressing race, which had brought her down into a state little different from slavery, and reduced her people to outcasts on the hunting-grounds which had belonged to her fathers" (31). The other Indian woman, Hota, is enslaved in the household of the flawed Pastor Tappau, also in Salem. Just as Tappau is clearly based on the historical figure of the Reverend Samuel Parris, Hota is more obviously based on the historical Tituba, whose "confessions" sparked the original charges, and whose story has "taken on nothing short of mythical dimensions" (Rosenthal, "Tituba's Story," 190). But both these women dabble in magic: "Hota one bad wicked witch, she say so herself; oh, me! oh, me!" says Nattee (74). It is now clear both that Gaskell pays homage to the episode narrated by Upham, and that she has her own story to tell, and her own way of telling it.

From this point, Lois is thrust into what are recognisably events based on the Salem Witch Trials, at least in the version that would have come down to Gaskell. "The witchcraft troubles had broken out in Parris's household," says Mather in his Diaries (70): here, then, they begin in Tappau's home, where his daughters, younger than the two girls in Parris's real-life household, are the first to seem afflicted. Seeing what is happening to them, local people are enraged and threaten Hota. No evidence exists that the historical Tituba was threatened by a mob, although she was arrested and spent many months in prison, so in this instance as elsewhere, Gaskell is adapting the original to suit her own purposes. However, Hota, like Tituba but unlike Gaskell's Nattee, escapes the gallows in the end.

Gaskell chooses not to deal with the process by which the Salem authorities conducted the judicial aspects of witchcraft panic, primarily in Salem itself, but followed throughout the colony. In these, English common law was practiced, and orderly judicial procedures were followed, including indictments, trials and Grand Jury hearings (see Rosenthal, Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692, especially Ch. 8). Having accurately portrayed the accusation leading to a presumption of guilt, Gaskell omits all the detail. These formal matters are not her concern. Instead, she chooses to move inexorably from accusation to execution, with a mob moving the process along. Nevertheless, she captures the basic point: if you were accused in 1692, as the fictional Lois was, you were likely to end up being found guilty. Once Lois is accused, and once Cotton Mather has come to Pastor Tappau's church to assist in the catching of witches, she is doomed.

Cotton Mather, as the frontispiece to his Diaries.

More directly for Lois's fate, her cousin Prudence suffers or creates — it is not entirely clear which — a convulsive fit, which occurs in the church while Cotton Mather is visiting. Mather and Tappau urge Prudence to identify who has cast this spell on her, and she names Lois. Nothing and no one can rescue Lois now. With undisguised irony, Gaskell has Lois, when thus accused, look at her cousin Faith and realise "that no good word was to be expected from her gloomy face and averted eyes" (96). Faith fails her. As for Manasseh, he is powerless to help. His argument to Mather, grounded in the great Puritan debate on the question of free will, is that since she had no free will Lois's behavior must have emanated from God. "Now, reverend sir, if the event be known to the spirit, it must have been foredoomed in the councils of God. If so, why punish her for doing that in which she had no free will?" (99). But Mather simply responds by warning him against blasphemy.

Gaskell is obviously aware of the deep theological problem of the Puritans, where human behavior must be judged against the inevitability of predestination, an issue most famously addressed by Jonathan Edwards in his sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of An Angry God," generally dated 8 July 1741. Gaskell dips into the topic without getting mired in the theological complexity, settling on a mob, along with Cotton Mather, angry with Manasseh, as the driving force here. There is no salvation for Lois in her cousin's plea. Gaskell, making an authorial appearance, writes "And you must remember, you who in the nineteenth century read this account, that witchcraft was a real terrible sin to her, Lois Barclay, two hundred years ago" (103).

Literary critics have tended to move the interest in this novella away from the historic trials themselves. Not concerned with how and why Gaskell departs from or manipulates the original narrative, they focus instead on her insights into human nature. Undoubtedly there is much to be learned from examining the various responses of Lois and the other characters (including Manessah, with his mental illness) to their predicaments. Looking for a unifying factor in them, and at the same time suggesting another reason for the story's continuing appeal, one critic finds a moral theme. None of the accusers, says Rebecca Sty1es, accept "moral responsibility for their actions, using their theology to justify the morally indefensible. They are "mistaken" [120] rather than evil, and their humanity prevents the reader from being wholly alienated from them" (84).

The work has also been related to Gaskell's canon rather than to its source material. Lois's relationships with Faith and Nolan, for instance, prompt another twenty-first century critic to compare it to Gaskell's earlier Ruth (1853) in its "subversion of lesbian and heterosexual desire," and to see this as "one of Gaskell's most compelling legacies" (Levy 94). But a more general link to her oeuvre is, perhaps, the way Lois's experience, like Ruth's, shows the "fundamental and ever-present danger of being led astray" (Krueger 36). In the Salem Witch trials, Gaskell found an outstanding example of this very vulnerability, and the need to combat it: "'Who knows?' is the refrain of her characters, faced with incomplete evidence and faulty explanations" (Kreuger 36). Gaskell's awareness of our fallibility is similar to Martineau's in her review of Upham's lectures in 1832. Such warnings are even more needed now, in an age when the risk of just one powerful figure acting on misinformation could have catastrophic outcomes for the whole human race.

Bibliography

Gaskell, Elizabeth Cleghorn. Lois the Witch and Other Tales. Leipzeig: Tauchnitz, 1861. Internet Archive. From a copy in Harvard University Library. Web. 10 June 2023.

Krueger, Christine L. Reading for the Law: British Literary History and Gender Advocacy. University of Virginia Press, 2010.

Levy, Heather. "'With Arms Entwined': Deadly Deceit and Romantic Friendship in Ruth and Lois the Witch" Elizabeth Gaskell, Victorian Culture and the Art of Fiction: Original Essays for the Bicentenary, ed. Sandro Jung. Gent: Academia, 2010. 83-98.

Martineau, Harriet. "On Witchcraft." Monthly Repository 6. Issue 68 (1832): 545-55. Internet Archive. From Open Court Publishing Co. Web. 10 June 2023.

Mather, Cotton. Diary of Cotton Mather. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1911. Internet Archive. From Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Web. 10 June 2023.

Rosenthal, Bernard. Salem Story: Reading the Witch Trials of 1692. Cabridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

_____. "Tituba's Story." The New England Quarterly 71, no. 2 (1998): 190–203. https://doi.org/10.2307/366502.

Styler, Rebecca. "'Lois the Witch': A Unitarian Tale." The Gaskell Society Journal 21 (2007): 73–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45185942.

Upham, Charles W. Lectures on Witchcraft, Comprising a History of the Delusion in Salem, in 1692. 2nd ed. Boston: Carter and Hendee, 1832. Internet Archive. From a copy in Harvard University Library. Web. 10 June 2023.

Created 10 June 2023