This is a chapter of Lewis Melville's Victorian Novelists (London: Constable, 1906: 239-257), in which Melville responds to the unaffected charm and vigour of Henry Kingsley's style and plots, suggesting that these qualities more than compensate for their weaknesses. The chapter has been transcribed, linked and illustrated for the website by Jacqueline Banerjee. It was not possible to separate the discussions of Recollections of Geoffry Hamlyn and Ravenshoe (Melville's focus here) completely; but headings and asterisks have been added to indicate shifts in focus. Page numbers, and occasionally the titles of the novels to which Melville refers, are given in square brackets.

Frontispiece to Recollections of Geoffry Hamlyn.

It is often difficult to find rhyme or reason for the decision of the public in questions of literature. Why, for instance, has Charles Kingsley been taken to the heart of the great mass of readers, while Henry Kingsley remains to them only a name? In vain may the entire field of conjecture be explored for a satisfactory explanation, for the qualities of the work of the younger brother are essentially popular. His stories are bright, imbued with humour and not without pathos, with plots more than sufficient to sustain the interest to the end, and character-drawing usually good and sometimes magnificent. In Australia the merits of Henry Kingsley have long since been recognised, but this is probably to be accounted for, not by the superior discernment of our cousins across the seas, but by the fact that he was the first writer of note to lay some scenes of his novels at the Antipodes. In England, however, he is rarely read and never discussed, save by a few men of letters: to the rest the name of Kingsley suggests always the Rector of Eversley, the popular preacher, novelist, and poet. Yet Henry has not been entirely without appreciation, for critics who [239/40] see life and letters so differently as Mr. Swinburne, Mr. Andrew Lang, and Mr. Augustine Birrell have united to praise him; while Mr. Clement K. Shorter has edited his works with a most praiseworthy enthusiasm. It is rather curious that it should be the critics, and not the public, who approve of this author. The general impression is that the critic is unduly by style; and perhaps this is not far from being as a rule the truth, for it cannot be denied that there have been writers who, possessing the gift of style and little else in the way of merit, have extorted high praise from those who sit in judgment. Now, never was there among English novelists worthy of serious consideration a writer less academic than Henry Eingsley. He had little sense of style, indeed often his English was slipshod, and on occasions even his grammar was not above reproach; and he has been accused, not without some show of reason, of many obvious faults -— of elementary solecisms, bad Irish and worse Scottish dialect, frequent improbabilities and occasional impossibilities. Also, it may be added, he was not averse to the repetition of situations, nor to the undue employment of coincidence. What a tribute, then, is the critics' approval!

The Recollections of Geoffrey Hamlyn and Ravenshoe

The secret of Henry Kingsley's attraction is the possession of the one quality that in the long run outweighs all others: he has the saving grace of charm. He is so human, too, so like a big rollicking schoolboy, that no one out of whose life [240/41] has gone the joy of youth should take up his volumes. He holds out to the reader the right hand of good-fellowship, while through every page shines a delightful personality. As he tells his story you cannot help listening, you cannot help being interested, you cannot help laughing with him. Who can keep a straight face when at the end of Geoffry Hamlyn he proceeds à la mode to make all his characters happy? He pairs them off in the most approved manner, until the only dissatisfied person in the book is Sam Buckley, whose dream it is to recover the ancestral estate of Clere. Now Sam, being a young man after the author's heart, must not have a wish ungratified. If he wants Clere, Clere he must have; and Henry Kingsley is the man to get it for him. With great seriousness he puts the matter right'

"Does any one of my readers remember that our dear old friend Agnes Buckley's maiden name was Talbot, and that her father owned the property adjoining Clere?"

"We do not remember," you say; "or at least, if we do, we are not bound to; you have not mentioned the circumstance since the very beginning of this excessively wearisome book, forty years ago." Allow me to say, that I have purposely avoided mentioning them all along, in order that, at this very point, I might come down on you like a thunderbolt with this piece of information; namely: — that Talbot of Beaulieu Castle, the towers of which were visible from Clere Terrace, had died without male issue. That Marian and Gertrude Talbot, the two pretty girls, Agnes Buckley's eldest sisters, who used to come in and see old Marmaduke when James was campaigning, had never married. That Marian was dead. That Gertrude, [241/42] a broken old maid, was sole owner of Beaulieu Castle with eight thousand a year; and that Agnes Buckley, her sister, and consequently, Sam, as next in succession, was her heir.

Then, just as you are feeling rather disgusted at this old-fashioned way of doing things — old-fashioned even for a writer in the sixties — you come across this footnote:

If you will examine the most successful of our modern novels, you will find that the great object of the author is to keep the reader in a constant state of astonishment. Following this rule, I give myself great credit for this coup de théâtre. I am certain that the most experienced novel reader could not have foreseen it. I may safely say that none of my readers will be half so much astonished as I was myself.

He has had his little joke — he was not serious, after all — in fact, was, amiably enough, poking fun at some of his contemporaries. You cannot help laughing at the fellow's impudence, if only because it is so obvious that he enjoyed this little burlesque very heartily.

But though in this case he had his tongue in his cheek, he was fond of introducing into his books genealogies so intricate that their accuracy has to be taken for granted, and with them the concomitant evils of secret marriages, children changed at birth, and other devices of a similar nature. This sort of thing was part of his equipment as a novelist — and indisputably the worst part: but it does not really matter, for plots are never with him very important, [242/43] although as a rule he constructed them carefully and kept up the mystery. Still, no one would read Henry Kingsley for the "story" alone. He would not be bound by any hard and fast rule, and he made havoc of the traditions of fiction.

"If I thought I was writing for a reader who was going to criticise my way of telling my story, I tell you the honest truth, I should tell my story very poorly indeed," he confessed in the course of one of his books.

Of course I must submit to the same criticism as my betters. But there are times when I feel that I must have my reader go hand in hand with me. To do so he must follow the same train of ideas as I do. At such times I write as naturally as I can. I see that greater men than I hare done the same. I see that Captain Marryat, for instance, at a particular part of his noblest novel, The King's Own, has put in a chapter about his grandmother and the spring tides, which, for perfect English and rough humour, it is hard to match anywhere. I hare not dared to play the fool, as he has, for two reasons. The first, that I could not play it so well; and the second, that I have no frightful tragedy to put before you to counterbalance it, as he had.

Then he pulls himself up with the remark that it is time this rambling came to an end, and that he hopes he has not rambled too far and bored his reader, which, he admits naively, "would be very unfortunate just now."

It is difficult to resist the refreshing simplicity with which he takes the readers into his confidence, and it is not quite fair to the critic, who cannot but be disarmed by it. He will interrupt the narrative to remark that if this or that had been done, then that [243/44] or this would not have resulted; or that this "is a crib from Sir E. B. L. B. L."; or that a reference to The Wild Huntsman will stop all criticism at this point, while a further reference to Faust will show him to be in good company. When Charles Ravenshoe comes to say goodbye to sweet Mary Corby, Lady Hainault leaves the lovers together and goes out of the room to look for a missing blotting-book. "And I intend to go after her, out of mere politeness, to help her to find it," he tells you.

I will not submit to be lectured for making an aposiopesis. If any think they could do this business better than I, let them communicate with the publishers, and finish the story for themselves. I decline to go into that drawing-room at presents I shall wander upstairs into my lady's chamber, after that goosey-gander Alwright, and see what she has done with the blotting-book.

Or, again, he gives the following passage:

When he said "Mary," in the old, old voice, there came such a rush of bygone times, bygone words, scenes, sounds, meetings and partings, sorrows and joys, into her wild, warm little heart, that with a low, loving and tender ciy she ran to him and hid her face on his bosom.

He mentions (in another of his delighted footnotes) that this paragraph from the word "Mary" to the end, is an experiment, for, as a matter of curiosity, he tried to write it without using a single word from the Latin; that, after having taken all possible pains to do so, he found there were eight out of forty-eight; and that he does not think it possible to [244/45] reduce the proportion lower, and thinks it undesirable to reduce it so low.

All these asides are dangerous — they would be fatal in a lesser man — but who can resist the good-humoured fooling of a man of genius? And what are you to do with a man, who, after remarking that Charles Ravenshoe found the banisters at Ranford better than those at home for sliding down, for they were not so steep, and longer, explains that "the best banisters for sliding down are broad oak ones with a rib in the middle. This new narrow sort, which are coming in, are wretched"; or who introduced Lord Palmerston with his umbrella on his shoulder, walking airily arm in arm with Lord John Russell? "They were talking together; and, as they passed, Charles heard Lord Palmerston say that it was much warmer on this side of the street than on the other. With which proposition Lord John Russell appeared to agree; and so they passed on westward." It seems as if the moment Henry Kingsley sat down to his desk — it is difficult to imagine him at work — he became like a boy out for a holiday. He was never afraid to joke, yet somehow his fun is never ill-timed nor his whimsical fancies out of place. There is no middle course to be adopted with his works; either yield to their fascination, or put them on the uppermost shelf and there for ever let them rest.

Henry Kingsley wrote tenderly of children, with whom he was always in sympathy; and quite affec[245/46] tionately of men and women. His characters were very real to him, and rather than shake them by the hand and say farewell, he introduced them into other books. He loved or hated the men and women of his creation, according to whether they are good or bad, and always grew very angry with his bad people; for instance, after pronouncing the handsome, heartless Adelaide Summers [in Ravenshoe] worthless, he says, "Let us have done with her. I can expand over good people, but I cannot over her." In truth, but for the exigencies of his stories, he would have none but the most worthy folk. As it is, Adelaide is almost an exception, for there are few irreclaimable characters in his books. It looks at one time as if her husband, young Lord Welter, would turn out a terrible scoundrel, but blackguard as he is, he saves himself in the end, when, from a sense of honour, after a herculean struggle between right and wrong, he does that which he believes will cost him a legacy of half a million sterling. Even George Hawker [in The Recollections of Geoffry Hamlyn], who seems lost and beyond hope, before he is led out to execution, being carried back in imagination to his old school-days, shows that there were good points in his character, and some good feeling which under other circumstances might in his youth have brought him to another end. "There is a spark of the Divine in the worst of men, if you can only find it," says our author, who believes that the only unpardonable crime is heartlessness [246/47].

Indeed Henry Kingsley is not happy except when he is dealing with his good folk, and them he treats with an exquisite loving-kindness. The Buckleys [also The Recollections of Geoffry Hamlyn], are depicted so as to secure affection forthwith, and there is a pretty little story of Mrs. James Buckley and her father at Clere waiting for news of the battle of Waterloo, in which James's regiment is engaged. At last an orderly comes from Portsmouth with a letter for the old man, and, while a maid goes to open the door, the wife asks at the window what has happened. "A great victory, my dear," said the man, mistaking her for one of the servants. "Your master is all right. There's a letter from him inside this one." "'And I dare say, Mrs. Buckley would add, when she would tell this old Waterloo story, as we called it, 'that the orderly thought me a most heartless domestic, for when I heard what he said, I burst out laughing so loud, that old Mr. Buckley woke up to see what was the matter, and when he heard he laughed as loud as I did.'" The author is obviously interested in beautiful, wilful, passionate Mary Thornton, who runs away with George Hawker, who marries her only for her money; and he is in love with her aunt, the ex-governess, who, when Mary returns with her child, runs forward, laughing wildly, and hugs the prodigal to her honest heart: "My darling! My own darling! I knew she would find her home at last. In trouble and in sorrow I told her where she was to come. Oh, happy trouble that has [247/48] brought our darling back to us!" Lifelike is the weak old vicar, who tries vainly to control his headstrong daughter; and so, too, is the Rev. Frank Maberly, who comes to his new parish for the first time, having run the last four miles of his journey in twenty-one minutes. But no man out of a book ever talked like Maberly, and it is a shame to make such a manly fellow talk like a prig, for that was the last thing in the world he was. This is the fault of Geoffry Hamlyn: that, while the characters are real, their conversation is impossibly stilted; and this grave defect is the more astonishing because there is not a trace of it in his other books.

The first part of Geoffry Hamlyn takes place in England; the second in the Australian Bush, where all the characters of the first part come, absolutely without exception — Hamlyn, the narrator; clever, handsome, good-tempered, reliable James Stockbridge, who is quite shamefaced when he discovers that he is no longer in love with Mary; the Thorntons, Maberly, the Brentwoods, and the Buckleys, Tom Troubridge, and the rest — country gentlemen, clergy [men, farmers, ex-convicts, labourers — not forgetting the villain of the story, George Hawker, who re-appears as the famous Touan. Still, it does not really matter that it is improbable, it does not really matter that, according to the law of probability, it must be some millions to one against all these people coming to the same spot some three hundred and [249/50] fifty miles south of Sydney, for the interest is so well sustained that the coincidence is not very distressing. Kingsley, who knew the bush-life well, is in his element in the chapters descriptive of it. There are alarums and excursions arising out of an attack by bushrangers, and a tragedy — that of George Hawker, in ignorance of the lad's identity, shooting his own son — and Kingsley, who loved to dally by the way, shows, when the storm bursts, when the crisis comes, that he can gather himself together and carry all before him in a breathless narrative.

Perhaps the figure that stands out best is Madge, the wild gipsy woman, whom old Hawker turns out of doors for aiding and abetting his son to deceive him. The Buckleys give her shelter for the night, and she shows her gratitude at her departure, when, with hand raised, she stands in front of the door, and in the grand, patriarchal manner, pronounces a blessing:

The blessing of God shall be upon the house of the Buckleys, and more especially upon yon and your husband, and the boy that is sleeping inside. He shall be a brave and a good man, and his wife shall be the fairest and best in the countryside. Your kine shall cover the plains until no man can number them, and your sheep shall be like the sands of the sea. When misfortune and death and murder fall upon your neighbours, you shall stand between the dead and the living, and the troubles that pass over your heads shall be like the shadow of the light clouds that fly across the moor on a sunny day. And when in your ripe and honoured old age you shall sit with your husband in a garden of your own [249/50] plantings in the lands far away, and see your grandchildren playing around you, you shall think of the words of the wild, lost gipsy woman, who gave you her best blessing before she went away and was seen no more.

A very different character is Mr. Secretary Pollifex [in The Recollections of Geoffry Hamlyn], who is undoubtedly drawn from life. A shrewd man of the world, with a dry humour that is most amusing. When Captain Blockstrop of H.M.S. Tartar invites hun to land at the small Australian settlement, he declines.

Not if I know it, sir, with pork chops for breakfast in the cabin. Blockstrop, have you duly reflected what you are about to do? You are about to land alone, unarmed, unprovisioned, among the off-scourings of white society, scarcely superior in their habits to the nomadic savages they have unjustly displaced. Pause and reflect, my dear fellow. What guarantee have you that they will not propose to feed you on damper, or some other nameless abomination of the same sort?

Later, however, he does land, and thus in feigned indignation addresses the Captain:

A failure, sir? Burnt, sir! Disgracefully burnt up to a cinder, sir! I have been consulting the honourable member of the Cross-jack-yard as to the propriety of calling a court-martial on the cook's mate. He informs me that such a course is not usual in naval jurisprudence. I am, however, of opinion that in one of the civil courts of the colony an action for damages would lie.

Other Novels

"I put another bullet into his head." Frontispiece to Valentin.

Besides Geoffry Hamlyn Henry Kingsley wrote a dozen novels, of which the best known are Ravenshoe; The Hillyars and The Burtons, a fine study of two [250/51] English families of different degrees; Mademoiselle Mathilde a story of the French Revolution into which are introduced Marat, Robespierre, Camille Desmoulins, and other personages of the period; Stretton,where part of the action takes place in India at the time of the Mutiny; Silcote of Silcotes, a tale of English country life; Valentine, a story of Sedan, based upon the experiences of the writer, who was present at the battle and claimed to be the first Englishman to enter Metz; and The Grange Garden, than which Mr. Clement Shorter thinks it would be impossible to conceive a worse novel written by an author of distinction.

Ravenshoe

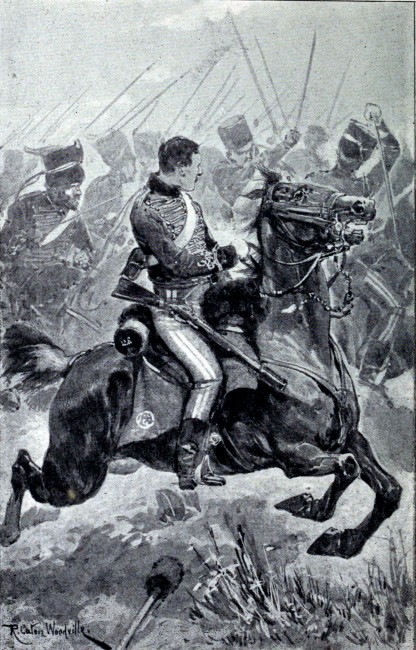

Ravenshoe is acclaimed by many as the masterpiece of Henry Kingsley, and at worst it is typical of him at his best. It is only necessary to read the first few pages to discover that the author is a consummate craftsman, for the book opens with a delightfully humorous account of the House of Ravenshoe, written with as complete a mastery of the subject as if the records of the family had been studied at the Herald's Office. The story centres round Charles, who is said to be William, not Charles, having been changed at birth, and who, when many years later he learns of the imposture, in spite of relatives and friends, goes out into the world, away from everybody he knows, becomes under an assumed name a groom, and, when his identity leaks out, enlists and goes with his regiment to the Crimea, where he is one of the six [251/52] hundred of the Light Brigade which made the famous charge. Although, like another great writer of fiction, Kingsley does not claim to rank among the military novelists, believing "our place is with the non-combatants: when the decks are cleared for action we go below and wait meekly," yet he finds himself in the midst of the battlefield at Balaclava. His description of that fierce struggle is stirring, and the passage with which he concludes is beautiful.

Oh, but the sabres bit deep that autumn afternoon! There were women in Minsk, in Moglef, in Tchernigof, in Jitemir, in Polimva, whose husbands were Hussars — and women in Taganrog, in Tcherkask, in Sanepta, which lies under the pleasant slate mountains, whose husbands and sons were Cossacks — who were made widows that day. For that day's work there was weeping in reed-thatched hovels of the Don, and the mud-built shanties of the Dnieper. For the 17th Lancers, the Scots-Greys, the 1st Royals, and the 6th Enniskillens — "these terrible beef-fed islanders" (to use the words of the Northern Bee) — were upon them; and Volhnyia and Hampshire, Renfrewshire and Grodno, Podolia and Fermanagh, were mixed together in one common ruin. Still, they say, the Princess Petrovitch, on certain days, leaves her carriage, and walks a mile through the snow barefoot, into Alexandroski, in memory of her light-haired handsome young son, whom Hornby slew at Balaclava. And I myself know the place where Lady Allerton makes her pilgrimage for those two merry boys of hers who lie out on the Crimean hill. Alas! not side by side. Up and down, in all weathers, along a certain gravel walk, where the chalk brook, having flooded the park with its dammed-up waters, comes foaming and spouting over a cascade, and hurries past the smooth-mown lawns of the pleasance. In the very place where she stood when the [252/53] second letter came. And there, they say, she will walk at times, until her beauty and her strength are gone, and her limbs refuse to carry her.

"Charles in the Balaclava Charge" (Ravenshoe. Frontispiece by R. Caton Woodville.

The author regarded Ravenshoe with much affection. "Of all the ghosts of old friends which I have called up in this quaint trade, the writing of fiction, only two remain and never quit me. The others come and go, and I love them well enough; but the two who are with me always are the peaked-faced man Charles Ravenshoe, and the lame French girl Mathilde." And well may he be proud of Charles — "who, it may here be divulged, is proved after all to be the eldest son of his father by an earlier and a secret marriage — for he is a gentleman to his finger-tips, a high-spirited, brave, loyal lad, beloved by all. But the hero is only one of a magnificent gallery of characters. Allusion has already been made to Mary Corby, to Adelaide, and to Lord Welter, a scion of the great house of Ascot which "for many generations had given themselves up entirely to sport — so much so, that their marriages with other houses have been to a certain extent influenced by it." The priest-ridden family at Ravenshoe is well depicted. Densil, the father, who rebels in his youth, but in spite of all his efforts, cannot escape from the influence; and Cuthbert, Charles's brother, who all too soon realises the worthlessness of the world and devotes himself to books and reUgious influences. The priests are even more [253/54] realistically portrayed. There is the simple-minded Father Clifford, and Father Tiernay, the jovial Irish-man, and Jesuitical Father Mackworth. It is the last-mentioned who is the great character. It is his object in life to keep the Ravenshoe family faithful to the Church of Rome, and he thinks no design wrong that assists him in his endeavour. He throws away a fortune so as to keep the House from falling into the hands of the Protestant Church. He is harsh, cruel even, yet cannot withhold his affections from the gentle Cuthbert; and there is nothing in the book more exquisite than the incident of the drowning of the latter.

The surf still gently playing with the sand, the sea changing from purple to grey, and from grey to black, under the fading twilight The tide sweeping westward towards the taU black headland, towards the slender-curved thread of the new moon, which grew more brilliant as the sun dipped to his rest in the red Atlantic. Groups of fishermen and sea boys and servants, that followed the ebbing tide as it went westward, peering into the crisping surf to see something they knew was there. One group that paused among the tumbled boulders on the edge of the retreating surges, under the dark promontory, and bent over something which lay at their feet. The naked corpse of a young man, calm and beautiful in death, lying quiet and still between two rocks, softly pillowed on a bed of green and purple seaweed. And a priest that stood upon the shore cried wildly to the four winds of Heaven, "Oh, my God, I loved him! My God! my God! I loved Him!"

Not a whit inferior to the priests are the great aristocrats. Lord Hainault, "one of the best fellows [254/55] in the world, but he would always talk as if he was in the House of Lords"; wonderful old Lady Ascot, and Lord Saltire, the most splendidly conceived of all the characters that Henry Kingsley ever drew. Lord Saltire is, to use the parlance of the theatre, the "star"; and when he is on the stage, although not always germane to the story, he is invariably the centre of attraction. He is an old dandy of the Radical Atheist set that flourished in the Regency, when those famous high-bred exquisites. Petersham, Sefton, and the witty Alvanley led the fashion — a gentleman as fine as ever Bulwer Lytton dreamt of or as George Meredith has depicted. In his youth a roué and a gambler with whom no man might play piquet and win, he yet contrived, while indulging in all the extravagances of his time, to keep his heart tender and pure. He had a merry wit which he was not afraid to use, as when he wants immediately a detective to search for Charles: "Go to Scotland Yard; give my compliments to Inspector Field; tell him a horrible murder has been committed, accompanied by arson, forgery, and regrating, with a strong suspicion of sorning, and that he must come at once"; or, again, when he addressed young Marston: "His young friend's father had not been a brilliant scholar, as my young friend was; but had been one of the finest whist players in England. His young friend had turned his attention to scholastic honours in preference to whist, which [255/56] might or might not be a mistake." Lord Saltire had had a son who was killed at an early age in a duel; and the memory of the poor lad was fresh in the old man's true heart, as fresh to the end, as it was on the morning forty years earlier when he came out of his dressing-room and met them carrying the corpse upstairs. But it was only one or two of his intimates who knew of this, for he rarely spoke of his son, and when he did it was generally in a cynical manner, under cover of which he was able to disguise the pain he still endured when the name was mentioned. Thus:

"I should like to have had a son like you, but it was not to be. I had a son who was all that could be desired by the most fastidious person brought up in a far better school than mine; but he got shot in his first duel, at one-and-twenty. I remember to have been considerably annoyed at the time," continued the old gentleman, taking a pinch of snuff, and looking steadily at Charles without moving a muscle, "but I dare say it was all for the best. He might have run into debt, or married a woman with red hair, or fifty things. Well, I wish you good day, and beg your forgiveness once more for the liberty I have taken."

Simplicity is the keynote of all the works of Henry Kingsley. His pathos is as simple as his humour, yet such was his command of both that he could at will create laughter or cause a tear to well to the eye. He could be as tender as a mother, as gentle as a dove. He had a love for things of beauty, and a poet's eye for nature, which showed itself in his [256/57] many admirable descriptive passages. He could depict the glories of the Thames Valley with as true a hand as he could paint those of the bush; and he was as much at home in sketching the society of an English drawing-room as in portraying the life of the early Australian settlers. There is no novelist with whom, in his entirety, he can be compared, though he had something of Lever's high spirits, and a love of his fellows as great as that of Charles Reade. There can be no doubt that the whirligig of time, which brings with it compensation as well as revenge, will put the works of this greatly gifted writer into a foremost place in the ranks of English novelists.

Bibliography

Melville, Lewis. Victorian Novelists. London: Constable, 1906: 239-257. Internet Archive, from a copy in the University of California Libraries. Web. 10 December 2023.

[Illustration source] Kingsley, Henry. Ravenshoe. London: Ward, Lock and Bowden, 1894. Project Gutenberg. Web. 10 December 2023.

[Illustration source] _____. The Recollections of Geoffry Hamlyn, with a memoir of Henry Kingsley by Clement Shorter, and illustrated by Herbert Railton. New ed. London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1894. HathiTrust, from a copy in Cornell University Library. Web. 10 December 2023.

[Illustration source] _____. Valentin: A French Boy's Story of Sedan. London: Routledge, 1874. Internet Archive, from a copy in Oxford University Library. Web. 10 December 2023.

Created 10 December 2023