Sylvia Hornsby has kindly shared with us this brief extract from Moving through Uncertainty with George Meredith (2023), her doctoral thesis for Canterbury Christchurch University. It deals with the impact of Meredith's health on his outlook and work, and helps to resolve the startling disjunction between his valetudinarianism and his exuberance. It has been slightly adapted, as well as formatted and illustrated, for our website. The whole thesis, with much more literary analysis, is available online at https://repository.canterbury.ac.uk. — Jacqueline Banerjee

ged thirty-two, Meredith refers to having been "struck down by illness" and being "knocked down again by the old illness," described as "horridly dispiriting" (Cline I: 58, 62). The illness was not specified, but a doctor’s diagnosis the following year was that "the 'knot of the nerves' is irritated and has long been so" (Cline I: 85). Towards the end of his life in conversation with the critic Marcel Schwob, Meredith said "I was born with a bad stomach" (qtd in Stevenson 317). The cause of his illness as a digestive disorder is mentioned in a letter written by William Hardman in 1862 recording that Meredith, then aged thirty-four, "has taken lately to felling trees and sawing up logs of wood, as a healthy exercise, to promote the circulation and improve his digestion. With the latter object in view he has also adopted a wet compress on his stomach, and has found great benefit from it" (Ellis 206, 207). In his fifties Meredith continued to suffer from the illness, by then diagnosed as bradypepsy, and experiment with self-treatment. In 1881 he wrote: "For a year digestion has been bad. I have had to discard Bacchus. By dint of exercise and ascetic fare, I am coming round" (Cline II: 615) and two years later, "I get some benefit from a recently imposed milk and fruit diet, meat and wine temporarily abjured" (Cline II: 704).

George Meredith, frontispiece to Bailey.

The effect of physical illness on mental well-being, and his ability to write, is mentioned by Meredith during the conversation with Schwob in which he referred to his "bad stomach." Meredith says that "They claim that the brain gets tired. Don’t believe it. The brain never gets tired. It is the stomach that conquers one" (qtd. in Stevenson 317). Experiencing the return of dyspeptic symptoms which affect his writing, Meredith [59/60] makes the link between stomach and brain, telling his friend Frederick Maxse: "Digestion is very queer with me; I cannot work long at a stretch just now, and that troubles me" (Cline II: 589). In a letter to another correspondent, Bonapart Wyse, he writes that the "malady, as of old, is bradypepsy influenced by the nervous excitement of composition continued too long’ (Cline II: 612). Meredith records the doctor’s treatment for the "knot of the nerves" stating: "I must not smoke, I must not work" (Cline I: 85) and his doctor "interdicts writing . . . the seat of the malady is the pen" (Cline II: 657). This was not unusual: the pain of facial neuralgia which Charles Dickens experienced at times of stress was also associated with the "tension of writing" (Kaplan 424) and twentieth-century studies suggest that the source of illness suffered by Thomas Carlyle and Charles Darwin was probably physiological. Meredith’s symptoms seemed to improve with rest, whereas Dickens refused to take advice, since restriction of intellectual creativity could result in dis-ease and depression, as recognised by the medical profession at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Meredith expresses his frustration at the conflict between physical health and mental wellbeing in a letter to his son Arthur, saying that: "My digestion is entirely deranged, and still I have to write - and for a public that does not care for my work." Referring to his "weak" stomach Meredith tells Arthur that it is "a form of weakness that incessant literary composition does not agree with" (Cline II: 627). To his son’s headmaster, the Rev. Augustus Jessopp, Meredith writes that he has been "very ill, the nerves prostrate. I think I am recovering, at the cost of abstention from work" (Cline II: 662). The medical view of the effects of mental strain was affirmed a decade later by Dr Kate Mitchell who states that "cramming" for examinations results in "feverish activity of the mind, languor and depression of the body . . . impaired digestion" (76). Meredith described the "benefit" of physical exercise and self-treatment in a letter to yet another friend, William Hardman, in terms of his ability to continue writing: "In consequence of the sweating and action of Compress, the stomach, where Emilia resides, is becoming an agreeable tenement, and I’m glad to say her features are improving’ (Cline I: 173).

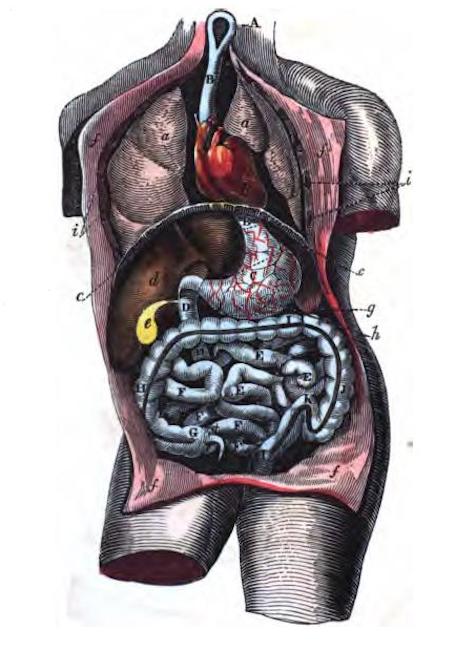

The stomach is brought forward for scrutiny in this colourful prefatory diagram in Jukes's On Indigestion and Costiveness (1831).

The growing interest in physiological systems (neural, respiratory and digestive) contributing to the "whole" man is reflected in contemporary publications which focussed on the interaction between the digestive system and brain. The degree of public interest is evident in the popularity of books which emphasised the importance of a healthy stomach. Edward Jukes, for instance, asserted that science was overcoming prejudice, confirming the advantages of "lavements" in preventing and curing disease of the digestive organs, in his book On Indigestion and Costiveness (1831), in which he promoted the use of the stomach-pump, his own invention ("Introduction," 1-5). Jukes was gratified by the "almost unprecedented rapidity" of [60/61] sales of this work, which was published in a fifth edition in 1836 (Preface to second edition, p.vii). A short book by barrister and author Sydney Whiting, Memoirs of a Stomach, published in 1853, was popular too: written with humour in autobiographical form, it imagines the personified stomach describing the effect of poor diet on health. This book was re-published over three decades. In fact, the link between stomach and brain had been made in 1836 by Andrew Combe, a Scottish physician and phrenologist, who concluded that since the sensation of hunger and thirst was experienced in the brain, "appetite" was comparable to the senses of "seeing, hearing, feeling" (The Physiology of Digestion, 13). Combe later built on this idea to express the concept of health and wholeness as a prerequisite for growth, publishing The Principles of Physiology Applied to the Preservation of Health, and to the Improvement of Physical and Mental Education (1852). Interest in physiology increased during the second half of the nineteenth century as knowledge accumulated.

Meredith particularly recommended the writings of G. H. Lewes and Alexander Bain for the study of "Mental Philosophy" emphasising that another of his many correspondents, Miss Ida L. Benecke, should "read them" (Cline II: 578). Bain published Mind and Body: The Theory of Their Relation in 1873 and founded Mind, the first journal devoted to psychology, in 1876.

The significance of digestion was also highlighted in popular publications aimed at general readers. The writer of an article of 1875 in Cassell’s Family Magazine (1875), titled "Your Digestion," asserts that "ugly, awkward dispositions . . . spring from indigestion" (443), and as in Memoirs of a Stomach the digestion is personified to warn against eating and drinking too much. The writer continues by saying that "digestion affects temper . . . and temper affects digestion" (443). An article in the 1879 issue of the same magazine, this time attributed to the "Family Doctor," advises on "Indigestion — Its Causes and Cure," stating that "indigestion or dyspepsia is the commonest of all diseases, 'the prevailing malady of civilised life’," and recommends diet, exercise and medicines "from the pharmacopœia" (175). In her Book of Hygiene in 1892, Kate Mitchell also laid great emphasis on digestion, stating that during "the years of childhood and adolescence, there are two organs of paramount importance in the system, the lungs and the stomach. Upon their proper health and working, the rest of the organs, structures, and tissues of the body are dependent’ (93).

Meredith uses his own experience of ill health not only to share knowledge of treatments in letters to friends, but also to convey awareness of physical symptoms on mental wellbeing in fiction. The character of Hippias Feverel in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel had the "ill luck to have strong appetites and a weak stomach" and is characterised as "the Dyspepsy" (5, 180). When his symptoms ease, Hippias experiences "ineffable relief to find himself looking out upon the world of mortals instead of into the black phantasmal abysses of his own complicated frightful structure’ (180). Meredith communicates understanding of the [61/62] unhealthy introspection caused by physical disease, and makes the link between brain and internal organs. Hippias attempts "to convey a glimpse of what hellish sufferings his had been" explaining to others: “My mind doesn’t so much seem to haunt itself, now . . . I feel as if I had come above ground” (180). In line with medical opinion emphasising the importance of diet and exercise for a healthy stomach, Meredith’s narrator acknowledges that "strong appetites" contribute to Hippias’ suffering. The implication is that he is at fault for failing to take responsibility for his health, although a "weak" stomach, as in Meredith’s experience, could be the result of a physiological problem, having no medical cure or treatment at that time.

Frontispiece of Sydney Whitings' Memoirs of a Stomach (1853) shows all too clearly the consequences of "strong appetites."

Different characters represent contrasting attitudes towards disease, implying personal blame for ill health or expressing sympathy for sufferers. "People said" that Sir Austin "only retained his boozing dyspeptic brother Hippias at Raynham in order to exhibit to his son the woeful retribution nature wreaked upon a life of indulgence" although the narrator refers to "poor Hippias" stating that this "was unjust" (74). Referring to the "poor Dyspepsy" the narrator repeats that "he is the one who never gets sympathy, or experiences compassion" (180). Liza Picard notes that "consumption" (also known as tuberculosis) "had overtones of... a sinful way of life" (233) and the view of suffering as a consequence of behaviour, to be accepted stoically, is expressed by the character of Adrian Harley, perceived ironically as "the wise youth," who states that "when our Nemesis takes lodging in the stomach, it’s best to act the Spartan, smile hard, and be silent" (181). His nephew Richard "alone was decently kind to Hippias" sharing physical exercise and mental stimulation with him, but Hippias soon experiences a recurrence of symptoms and goes "underground again" (181). Referring to "'the doctors!' . . . with vehement scepticism" Hippias asserts that "No man of sense believes in medicine for chronic disorder . . . They advertise a great many cures for indigestion . . . I see no reason why there should be no cure for such a disease" (181). The sense of Meredith’s pragmatic acceptance is combined with an optimistic interest in medical research as Hippias ponders the possibilities "if we could by any means appropriate to our use some of the extraordinary digestive power that a boa constrictor has in his gastric juices" (182).

While it clearly influenced him, Meredith also questioned the nineteenth-century perception of health in his fiction, most notably in relation to gender stereotypes. The concept of Muscular Christianity, a term associated with Charles Kingsley’s writings, emphasised physical strength to denote masculinity, and social opinion valued the importance of health, wealth and status. Men in a position of power assumed authority over others, and women as the weaker sex were expected to conform to the [62/63] role of Coventry Patmore’s "Angel in the House." The movement towards greater freedom and independence is recorded in Women and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England by Joan Perkin, who refers to the significant achievement of legal rights, while noting the difficulty in changing society’s perception of women’s status and roles. As Perkin says, "the emancipation of women, in marriage as in life in general, is more than a question of law or theory. It can only stem from the attitudes and behaviour of men and women themselves"(8). Changes occurred only gradually. The expression of long-held views of women as inferior to men persisted in publications, suggesting that any change to the model of femininity could affect a woman’s health, and was a potential threat to the structure of society. Meredith challenges gender stereotypes as being unhealthy for oneself and for others. Analysis of passages from The Egoist (1879) and Lord Ormont and his Aminta (1894) demonstrates how Meredith depicts the model of the hero as egoistic and unhealthy, introspective and inactive. The egoist’s development is shown to be limited by his restricted outlook, and lack of engagement with others or the natural world. Using enclosed indoor space as a metaphor to emphasize restriction of place and attitude, Meredith shows that the effect of egotistical behaviour imposed on women causes dis-ease and depression. He expresses criticism of those who condone or perpetuate outdated attitudes.

Much as George Eliot expresses in Middlemarch the need to emerge from the "moral stupidity" into which we are all born (198) so Meredith stresses repeatedly the need for individuals to progress beyond egoism, to move from a primitive to a civilised state, and towards a better civilization in which both men and women can play their part. He is critical of the selfishness of egoism noted by Judith Wilt as "unhealthy" (8) for restricting the development of the individual and others. Meredith warns of the danger of egoism in his poem "The Woods of Westermain," described by Phyllis Bartlett as "an allegory in which Self, an inflated belief in the importance of one’s personality, is the Dragon in the woods of life" (xxxiv). In his fictional characters Meredith shows the cold indifference of egoists whose restricted outlook limits their interaction with others, in contrast to the warm vitality of characters with body, mind and spirit moving towards harmony, and in close relationship with each other and the natural world.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Bailey, Elmer James. The Novels of George Meredith: A Study. New York: Scribner's, 1907. [Illustration source]

Bartlett, Phyllis. Introduction. The Poems of George Meredith. 2 volumes. Vol. I: xxvii-xliv. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1978.

Eliot, George. [1871-2] (1996) Middlemarch. 1871-72. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Ellis, S. M., ed. A Mid-Victorian Pepys: The letters and memoirs of Sir William Hardman. London: Cecil Palmer, 1923.

A Family Doctor. "Indigestion — Its Causes and Cure." Cassells Family Magazine. Vol. V (1879): 174-75 . Internet Archive. Web. 1 October 2024.

Jukes, Edward. On Indigestion and Costiveness. London: John Churchill, 1833.

Kaplan, Fred. Dickens: A Biography. Sevenoaks: Hodder and Stoughton, 1988.

Meredith, George. The Letters of George Meredith. 3 Vols. Edited by C. L. Cline. Oxford: Clarendon. 1970.

_____. The Ordeal of Richard Feverel. 1959. London: Constable, 1913.

Mitchell, Dr Kate. The Gentlewoman’s Book of Hygiene. London: Henry and Co., 1892.

Perkin, Joan. Women and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England. London: Routledge, 1989.

Picard, Liza. Victorian London: The Life of a City 1840-1870. 2005. London: Phoenix, 2006.

Stevenson, Lionel. The Ordeal of George Meredith. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953.

Wilt, Judith. The Readable People of George Meredith. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1975.

"Your Digestion." Cassells Family Magazine. Vol. I (1874): 443-444. Internet Archive. Web. 1 October 2024.

Created 1 October 2024