This review is reproduced here by kind permission of the author and the online inter-disciplinary journal Cercles, where it was first published. The original text has been reformatted and illustrated for the Victorian Web by Jacqueline Banerjee, who has also added captions and links. Click on the images for larger pictures and more information.

Cover of the book under review.

Mythological stories of underground worlds have been an integral part of human culture for millennia. The Norse myths of Odin and Valhalla, the Greek myths of Hades and Persephone, and the Roman myths of the Inferno, particularly the use of the underworld by Dante in his Divine Comedy, will be familiar underground territories to the Western reader. But subterranean mythology is not restricted to Europe and the underworld is an important part of ancient human culture globally, from the Maori Hawaiki to the Inuit Adlivun, from the Shinto Yomi to the Inca Ukhu pacha. Haewon Hwang's fascinating study of the spaces beneath Victorian London demonstrates the continuing interest in (and repulsion by) the ground beneath our feet in the modern world, even for those industrial, scientific, rational Victorians.

Hwang divides her analysis of the Victorian underground into four spaces: the network of sewers, the underground rail system, cemeteries and – in a more abstract form of "underground" space – the resistant, left-wing political movements of the late nineteenth century. Each space is investigated through the lenses of history, politics, art and literature, and discussed in some depth (pun intended) to consider the visibility of power and resistance in these underground spaces. Hwang draws on the theories of space and power by philosophers such as Henri Lefebvre and Michel Foucault to make visible the tensions between "upper" and "lower," whether that is the opposition of physical spaces or relations in a power struggle, and the Derridian notions of "spectrality" and "non-presence" to consider the "haunting" of the surface by the spaces of the underground.

Left to right: (a) Labourers laying sewers in the city streets in Ford Madox Brown's famous Work. (b) Gravestones relocated to make room for railways, at St Pancras churchyard, an operation overseen by the young Thomas Hardy. (c) The Metropolitan Railway, the world's first underground passenger service, shortly before its official opening.

The author opens the book with the statement that this is not simply a history of the underground or a mapping of subterranean spaces, but a consideration of the underground on the imagination. But for this reviewer, the book is strongest when dealing with the historical attitudes to and uses of the underground spaces. The chapter dealing with the massive undertaking of building the London sewerage system sets out both the logic and rationality of the engineering feat bringing a new hygiene to the festering city as well as the effect this project had on the social divide between rich and poor, high and low, clean and unclean. While the sewerage project brought — or at least attempted to bring — order and cleanliness to London as a whole, it also had the effect of bringing into visibility the city's "low life" as slum areas were ripped apart to lay the drainage system. The development of the underground transport system similarly broke through not only to the physical depths beneath London but also to the "depths" of the previously invisible habitations and habits of the metropolitan working class. These projects, and the relocation of the cemeteries to the outer limits of the city, brought "the underground, previously unseen and ungoverned" into physical and psychological visibility, which then turns it into a "site of discipline and rationalisation as the space becomes co-opted by ... authorities and capitalist enterprises" (9). Movements designed (and desired) to bring cleanliness and to ease congestion simultaneously broke down spatial barriers of gender and class as workers and women also moved more freely and were less easily contained within designated spaces. Although these changes raised fears of moral infection and temptation, the desire for financial profit trumped these concerns as even the graveyards generated interest by and for the joint-stock companies. As Hwang states:

The correlation of death and illness then aligned the corpse with diseases and pestilence, placing cemeteries in the same medical discourse as the sewers in the secularisation of burial practices. This correlation inevitably took the subject of death from the religious realm to a political one in the eradication of graveyards and cemeteries from the city centre. [117]

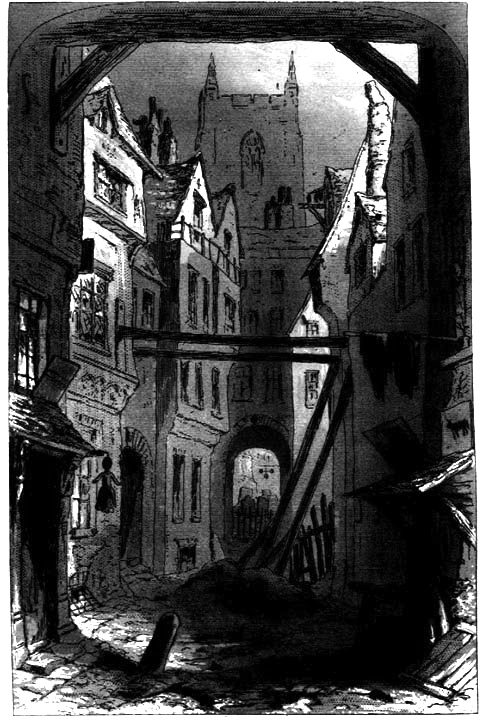

Tom-All-Alone's in Dickens's Bleak House, by Phiz.

The difficulties of imposing bourgeois order on the subterranean movement of waste and the movement or stasis of bodies (living and dead) are not only evident in historical records but also in the literary works of authors including Charles Dickens and George Gissing as well as sociological investigators like Henry Mayhew and Friedrich Engels. However, it is in the literary analyses that the study loses some of its clear focus and intellectual depth. While the author acknowledges the metaphorical use of the sewers in, for instance, Dickens's presentation of the human waste inhabiting Tom-All-Alone's in Bleak House or the freedom grasped by Gissing's female characters' use of the underground railway in The Odd Women there is little interpretation of the ideological underpinning of these literary spaces. For example, the author notes that Gissing's novel, The Nether World, presents a "cyclical if not static" plotline and claims that Gissing's characters "choose of their own will to live a subterranean existence without any hope for mobility or salvation" (36-37) without considering the criticism of Gissing's naturalism presenting a restrictive image of working-class life. If this book had been simply a historical account of the Victorian ordering of the underground space then the presentation of the literary text as a form of historical document would have been fine but as it is described as an analysis of the Victorian imagination as well as the physical space then a more detailed examination of literary representations is necessary.

In fact, it is when the book moves into the literary analysis of the cemetery in Victorian literature that it begins to lose focus — in both argument and space. After the discussion on the relocation of burial grounds from the centre to the outskirts of the city, the chapter moves on to consider East End poverty as a secular version of Hell and the analysis of literary burials takes us away from London to the Essex countryside of Mary Elizabeth Braddon's Lady Audley's Secret, through the Yorkshire moors of Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (with only a tenuous link to London through Lockwood) and out to Austria's Styria in Sheridan LeFanu's Carmilla. I would at least have expected to see some detailed analysis of Stoker's presentation of Highgate cemetery in Dracula and the final scene of Gissing's The Nether World in Abney Park cemetery considering both of these novels had already been discussed in earlier chapters.

Another kind of "underground": William Strang's Socialists (1891).

The final chapter on underground political movements in London is a fascinating concept but one which would have benefited from reordering and expansion. Hwang recognises the importance of the political threat in novels by Henry James, Joseph Conrad, Walter Besant and George Gissing but fails to consider the political ideologies of the authors through which these threats are projected. At one point Besant's sympathetic liberalism is likened to George Bernard Shaw's Fabian socialism, a pairing at which both men would have bridled. The fears of small-c conservative and anti-socialist authors do have a place in this chapter but their attitudes are not given enough attention, their differences are not emphasised nor are the images of political revolt acknowledged as attempting to reinforce the status quo. There is also a complete absence of the literature of the political "underground" itself: literary representations of London abounded in the fiction of both the Chartist and socialist movements and there ought to have been space found in this chapter to consider the other side of this political coin.

Nonetheless, this is an engaging study of the Victorian attitudes towards and fears of the invisibility and disorder of the ground below. At its best, this book is an interesting, informative and thoughtful work, which brings the depths of the metropolitan underground spaces into the light of intellectual enquiry.

Bibliography

Hwang, Haewon. London's Underground Spaces: Representing the Victorian City, 1840-1915. Edinburgh Critical Studies in Victorian Culture. Edinburgh: University Press, 2013. Hardback. 264 pages. ISBN 978- 0748676071. £70.00.

Created 18 February 2016