he son of a farmer in Fife, Archibald Constable developed an interest in books after visiting a local bookshop in the small Fife fishing port of Pittenweem. In 1788, his father arranged for him to be apprenticed to Peter Hill, an Edinburgh bookseller, and the fourteen-year old gradually rose to a position of trust in the firm, being sent out to auctions with the power to make buying decisions. Hill was not especially interested in antiquarian books, but Constable was and, soon after his marriage in 1795, his father-in-law helped him set up his own business in the High Street in Edinburgh, specializing, as the sign above the shop read, in “Scarce Old Books.” The shop did well and in 1798 Constable ventured into publishing with a volume entitled Fragments of Scottish History and a collection of Doctrinal and Occasional Sermons by the evangelically-inclined preacher and theologian John Erskine (1721-1803). In 1801 the young bookseller/publisher acquired the venerable Scots Magazine, the first volume of which had appeared in February 1739 (it claims to be “the oldest magazine in the world still in publication in 2018”), and which regularly published wide-ranging articles and essays, reviews, poems, and current reports from all parts of the world. As its editor, he appointed the notable Scottish Orientalist John Leyden, who had a lively interest in Scottish poetry and was something of a poet himself.

Archibald Constable by an unknown artist. Courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland D2696. Click on image to enlarge it.

The great turning-point in the history of Constable as a publishing house occurred in November, 1802 with the appearance of the first issue of the Edinburgh Review, which has been said to have been “arguably the most politically, socially, and aesthetically significant periodical in British history,” even if some of the early reviews in it – notably of work by Wordsworth, Coleridge, Southey, and Byron — were unduly provocative and ill-judged (MacKenzie, pp. 49-56). The Edinburgh Review continued in operation until 1929. The British writers represented or reviewed and discussed in its pages in the course of the nineteenth century and into the first decade of the twentieth included Matthew Arnold, George Borrow, Robert Burns, Lord Byron, Thomas Chatterton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Cowper, Thomas Campbell, George Crabbe, Benjamin Disraeli, Maria Edgeworth, George Eliot, Edward Gibbon, Oliver Goldsmith, Thomas Gray, David Hume, Francis Hutcheson, Washington Irving, Samuel Johnson, Charles Lamb, James Macpherson, Thomas Moore, Amelia Opie, Alexander Pope, Anne Radcliffe, Thomas Reid, Samuel Richardson, William Robertson, John Ruskin, Walter Scott, Percy Shelley, Adam Smith, Robert Southey, Alfred Tennyson, James Thomson, Anthony Trollope, Horace Walpole, Thomas Warton, and William Wordsworth. In addition, the Edinburgh Review not only covered these major (or then popular) British poets, novelists, essayists, and writers on philosophy, politics, economics, and science but also great foreign writers, such as Alfieri, Balzac, Goethe, Alexander von Humboldt, Klopstock, Kotzebue, Lesage, Lessing, Marivaux, Prévost, Mme de Staël, and Voltaire.

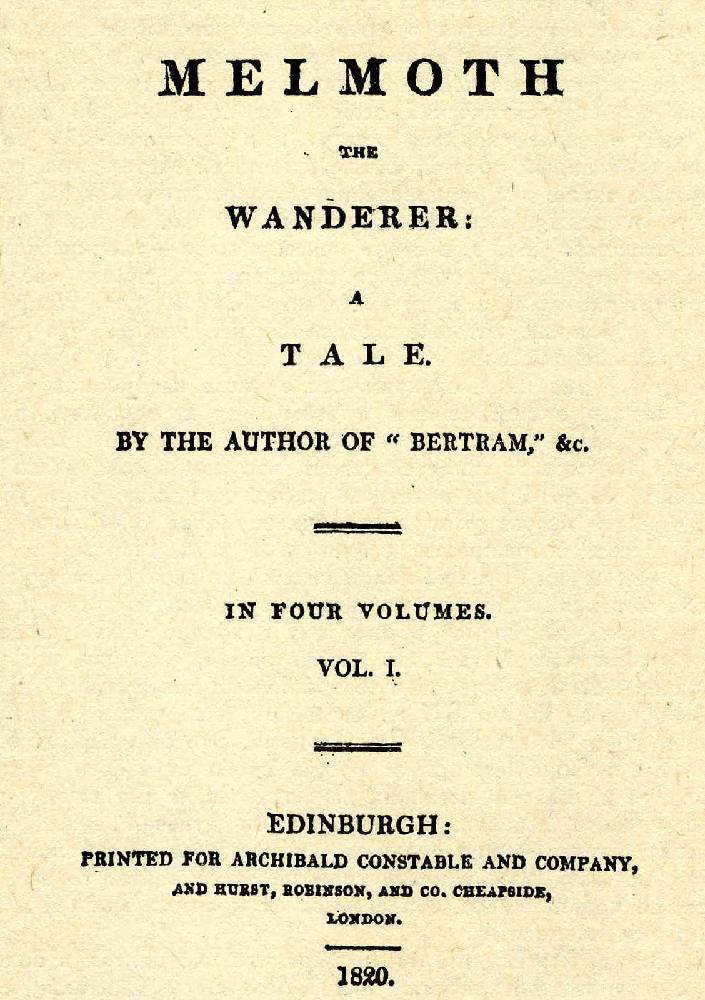

In 1805 Constable ventured into novel publishing with an anonymous work entitled Belville House, co-published with a London and a Dublin firm; The Mysterious Visitor, or Mary, the Rose of Cumberland by Henry Montague Cecil, co-published with Longman of London; and Adeline Mowbray, or The Mother and Daughter, also with Longman, by the prolific and widely read Mrs. Amelia Opie. Throughout the years, while a great deal of his output consisted of writings on law, science, medicine, travel and exploration, and theology (a fact that is easily overlooked), he continued to publish fiction by popular writers of the time or by writers with a Scottish connection, often in association with the London publisher Longman or, as of about 1820, Hurst Robinson. Among them: William Godwin, Mandeville. A Tale of the Seventeenth Century in England (1817), Mary Brunton, Emmeline (1819, with John Murray), Miss [M.G.T.] Crumpe, Isabel St. Albe; or Vice and Virtue. A Novel (1823), Catherine Cuthbertson (no author’s name given), The Hut and the Castle (1823), John Campbell Colquhoun (no author’s name given), Zoe: An Athenian Tale (1824), George Borrow (no name given, but with a dedication to the Scottish woman poet Joanna Baillie), Tales of the Wild and the Wonderful (1825), Catherine Grace Godwin (a Glasgow-born poet, painter, and novelist, no name given), Reine Canziani: A Tale of Modern Greece (1825), and three works by the successful novelist and playwright Charles Robert Maturin (identified as “the author of . . .”, no name given), Woman, or Pour et Contre (1818), Melmoth The Wanderer (1820, the work for which he is best known), and The Albigenses: A Romance (1824).

Constable’s most significant and influential author, however, was always Sir Walter Scott. In 1802, Constable purchased a share in the third edition of Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802) and partnered with Longman of London — also for a time the London agent for the Edinburgh Review — in the publication of Scott’s edition of the thirteenth-century romance Sir Tristrem (1804) and again in that of Scott’s first significant original success, The Lay of the Last Minstrel (1805), which by the time it went into a fourteenth edition in 1825 had sold over 30,000 copies. In 1807 Constable offered Scott £1,000 in advance for his next major poem, Marmion (over 50,000 copies sold by 1836). The following year, at Scott’s urging, Constable published – this time in partnership with John Murray — Quenhoo Hall: A Legendary Romance, interspersed with poems and songs, by the recently deceased antiquary, engraver, and author Joseph Strutt (1749-1802). The work had been edited and partly written by Scott, who also provided a Preface for it.

In the wake of a critical review of Scott in the Edinburgh Review, a split occurred in 1808 between Constable and his most outstanding author, whereupon Scott transferred his business to the publishing firm of John Ballantyne & Co., for which he himself had supplied most of the capital and which was in fact his own venture into the publishing business. In 1813, however, a reconciliation took place. Ballantyne was in serious financial difficulties, and Scott approached Constable with a request to help out. As a result, Constable again became Scott's publisher, the condition being that Constable was to buy out the stock of the Ballantyne firm, which in turn was to be wound up at an early date. Scott was nevertheless to retain his interest in the printing business of James Ballantyne & Co. (See Constable, I, 138-39, 382; MacKenzie, pp. 52-53; and Macleod, pp. 8-9).

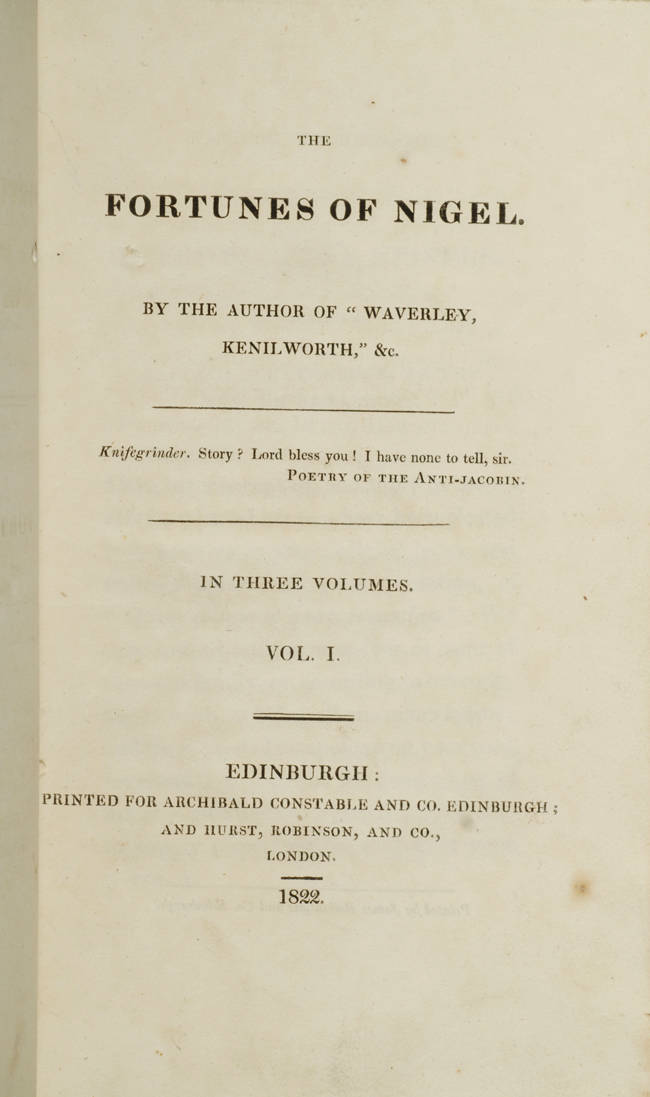

In the years that followed, Constable put out an impressive number of Scott’s works. In 1814, following the renewal of his relationship with Scott, he bought the copyright of Waverley, the author’s first venture into prose composition. At Scott’s insistence, it was issued anonymously. Anonymity was not unusual at this time, some authors preferring to define themselves by earlier, easily recognizable publications: thus in Scott’s case, “by the author of Waverley” or in that of John Galt, “by the author of Annals of the Parish.” Scott’s Waverley quickly sold 12,000 copies, his other novels followed in quick succession, and all sold well: Guy Mannering in 1815, The Antiquary in 1816, Rob Roy in 1818, The Abbot, Ivanhoe, and The Monastery in 1820, Kenilworth in 1821, The Fortunes of Nigel, Peveril of the Peak, and The Pirate in 1822, Quentin Durward in 1823, Redgauntlet and St. Ronan’s Well in 1824, Tales of the Crusaders in 1825, and Woodstock, or The Cavalier. A tale of the Year Sixteen Hundred and Fifty-One in 1826.

In 1812 Constable, at the height of success, purchased the copyright of the Encyclopædia Britannica, and added a significant supplement of six volumes (1816-1824) to the 4th, 5th and 6th editions. As part of his deal with Scott, he also took over the Edinburgh Annual Register, a bulky annual which had been Scott’s idea and had first been put out by Ballantyne in 1808, along with the Ballantyne company’s stock of unsold copies of that massive publication. The first volume to appear under the Constable name — that for the year 1814 — came out in 1816, as a thick volume of over 400 pages. Part 2 contained poems by Byron (“The Guerilla”), Wordsworth (“The Stranger”), Coleridge (“Isabelle”), Southey (“Peter of Barnet”), James Hogg (“Prayer of a Dying Soldier on the Field of Waterloo”) and three unsigned sonnets. It also included 27 closely-printed pages of bibliography for the year, arranged by subject matter with — alongside those on Botany, Chemistry, History, Hydrology, Law, Mathematics, Mechanics, Medicine, Philology, Philosophy, Political Economy, Theology, and the like — substantial sections on “Novels and Romances” and “Poetry” (one of the longest). The bibliography of novels drew attention to many works by woman novelists. In addition to Jane Austen: Mrs. Bridget Bluemantel (a.k.a. Maria Elizabeth Budden, 1780-1832), Laetitia Matilda Hawkins (1759-1835), Elizabeth Hervey (1748-1820), Barbara Hofland (1770-1844), Fanny Holcroft (1745-1809), Elizabeth Meeke (1761-1826), Sydney, Lady Morgan (1781-1859), Matilda Regina Roche (1764-1845), Elizabeth Isabella Spence (1768-1832), Ann of Swansea (a.k.a. Ann Julia Hatten, 1764-1838). (For information about these and countless other women writers of this time, see the remarkable Feminist Companion to Literature in English and Garside).

The Annual Register proved as big a burden to Constable, even after a drastic reduction of the number of copies printed, as it had been to Ballantyne since its first launching. (According to “Financial Hardship,” an article on the Scott Library website, it was losing £1,000 a year by 1812.) Over-speculation added to the firm’s financial difficulties, and in 1826 when there was a general financial crash, Constable's London agents stopped payment, and the firm failed for over £250,000, while the printing business of James Ballantyne & Co. also went bankrupt for over £90,000. Scott, having contracted the Ballantyne’s bills, was affected by the failure of both firms, so that he too went bankrupt. To add insult to injury, Constable learned that Scott would thenceforth publish with another publisher. As for the Edinburgh Review, publication was taken over by Longman.

Another casualty of the Constable firm’s financial collapse was a projected Elementary Encyclopedia. In August, 1823, Constable had informed Maria Edgeworth, the influential novelist and author of children’s books, with whom, thanks to Scott, he entertained friendly relations and a correspondence, of his plans for an “Elementary Encyclopaedia for Youth.” He had also discussed the project with her during a visit she had made to Scotland and had sounded her out – unsuccessfully — about becoming one of the project’s editors. Toward the end of 1824 he had sent her a printed list of the proposed contents, along with a request that she contribute articles on “Female education,” “Etiquette,” and “Recreations – Rational and Useful for the Female Sex.” In her response of a few weeks later, Edgeworth had greeted the proposal positively, while offering some suggestions for making the projected work more useful and accessible to its intended readership of less educated or young people. “In referring to an encyclopaedic dictionary, young people especially want immediate and precise information of the meaning of certain terms, or of the means of accomplishing certain purposes. It should be therefore more practical than theoretic. If I were you, in the first place I would weed out all the heads in your present prospectus which would be general treatises, and class the others into what are essential, necessary in the next degree, and so on. When you have thus got rid of what is obviously superfluous for your purpose, compress again and again till you get your design into the smallest compass that will hold the needful” (Constable, II, 405-12). The Encyclopedia, which Constable had hoped would begin production in May, 1825, with all four volumes out by 1827, never materialized.

The title-pages of three works published by Constable. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Constable’s ambitious, pioneering plan for a series of mass-produced, cloth-bound books to be known as Constable’s Miscellany – selling for one shilling each and designed to make “Original and Selected Publications in the various Departments of Literature, Science, and the Arts” available to the less well-off members of society – was also a near-casualty of the company’s fall into bankruptcy. As announced on the first page of the first volume, with its dedication to King George IV, “This Miscellany” is “designed to extend useful Knowledge and elegant Literature by placing Works of Standard Merit within the attainment of every Class of Readers.” Constable’s Preface to the first volume, dated Edinburgh, December 1825, expands on this theme. The entire project – “one of the most significant publishing breakthroughs of the nineteenth century,” in the words of the historian D. A. Low — was clearly inspired by the characteristic Scottish emphasis on education and the dissemination of knowledge and culture:

The change that has gradually taken place during the last thirty or forty years in the numbers and circumstances of the reading public, and the unlimited desire of knowledge that now pervades every class of society, have suggested the present undertaking. Previously to the commencement of the late war, the buyers of books consisted principally of the richer classes – of those who were brought up to some of the learned professions, or who had received a liberal education. The saving of a few shillings on the price of a volume was not an object of much importance to such persons, many of whom prized it chiefly for the fineness of its paper, the beauty of its typography, and the amplitude of the margins – qualities which add to the expense of a work, without rendering it in any degree more useful. But now, when the more general diffusion of education and of wealth has occasioned a vast increase in the number of readers and in the works which daily issue from the press, a change in the mode of publishing seems to be called for. The strong desire entertained by most of those who are engaged in the various details of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, for the acquisition of useful knowledge and the cultivation of their minds is strikingly evinced by the establishment of subscription libraries and scientific institutions, even in the most inconsiderable towns and villages throughout the empire. [pp. 256-59; see also Altick, pp. 287-69.]

Though the Miscellany did get off the ground, it was not without difficulty or delay. In 1825, Constable traveled to London to seek financial support for his project but banker after banker showed him the door. He returned to Edinburgh and fell ill with dropsy (edema). Another trip to London in January 1826 was equally futile, and in the middle of that month it became known that Constable and Company could not meet its obligations. Though it had been strongly endorsed by Walter Scott, the projected Miscellany could not count on material support from the great writer, whose financial situation was also dire. The naval captain and explorer Basil Hall, one of the Constable firm’s authors (Account of a Voyage of Discovery to the West Coast of Corea and the Great Loo-Choo Island in the Japan Sea, 1818), who had been scheduled to contribute an early volume to the Miscellany, generously offered to donate his manuscript. Replying on May 29, 1826, to Hall’s gesture, however, Constable was still not confident that his project would survive: “I cannot positively say that the arrangement for the Miscellany with my trustees will be completed within a week, though I hope it may be so” (Constable, II, 491-99). According to his son, the work in question, The Life and Discoveries of Captain Cook, which Constable had declared to be “an indispensable article in his Miscellany, was never written.” In the event, Constable did succeed in getting publication started, just before his death, in his early fifties, in July 1827. The first volume (1826) was a reprint, revised and enlarged, of Hall’s 1818 Account of a Voyage of Discovery to the West Coast of Corea. Another work by Hall, in two volumes (Extracts from a Journal Written on the Coasts of Chile, Peru, and Mexico in the Years 1820, 1821, 1822), made up volumes II and III of the Miscellany. After Archibald Constable’s death, the program was continued by his son Thomas, who took over the firm. In conformity with Constable’s plans for the collection, most volumes were devoted to “practical” topics (history, geography, engineering, travel accounts, etc.). Early texts of a somewhat more literary character include a reprint of the Memoirs of the Marchioness de la Rochejacquelin, edited with a Preface by Sir Walter Scott (vol. V, 1827); Lockhart’s Life of Burns (vol. XXIII, 1828); Robert Chambers’ two-volume History of the Rebellions in Scotland in 1689 and 1715 (vol. XV, 1828), followed by his History of the Rebellions in Scotland under the Marquis of Montrose (vols. XXXXI and XXII, 1828); and The Historical Works of Friedrich Schiller, in two volumes [Wallenstein and The Thirty Years’ War] (vols. XVIII and XIX, 1828).

The first volume of the Miscellany includes (pp. v-viii) a four-page list of over fifty proposed future volumes. These include, besides many works of ancient and modern history and biography (including a “Life of General Washington” and the “Life of Benjamin Franklin by Himself,” each occupying two volumes), studies of political economy and monetary systems, books on road-making and railways, “Economic Cookery for the Rich and Poor,” and “Devotional Exercises, Prayers, and Meditations.” Constable’s sense that inexpensive books would be instruments not only “for enlightening and entertaining mankind” but “for making money“ (in the words of Scott’s son-in-law and biographer Lockhart) is emphasized by Richard D. Altick in The English Common Reader (pp. 207-08).

In 1839, just over a decade after Archibald Constable’s death, C. H. Timperley, the author of a Dictionary of Printers and Printing, paid tribute to him. “A man joining such professional abilities to such liberal and extensive views; so capable of appreciating literary merit, and so anxious to find for it employment and reward; as largely endowed with the discernment, tact, and manners, necessary to maintain a useful, honourable, and harmonious intercourse with literary men, is not a common character, even among the improved race of modern bibliopolists” (p. 902).

The business of the Constable firm was carried on by the publisher’s son Thomas, who also took over and expanded the Edinburgh printing business of his grandfather, David Willison (Archibald Constable’s father-in-law). In 1839 Thomas was appointed printer to Queen Victoria and in 1859 printer to Edinburgh University. By 1852 the company had sixteen presses and fonts for printing in Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Sanskrit and German, as well as for printing music. As printer, T. Constable produced books for several major London publishing houses. He did not abandon publishing, however. As noted, volumes for the Miscellany continued to appear, along with new works — under the name T. Constable, Edinburgh — primarily in history, philosophy, science, and religion, such as Alexander Wilson’s American Ornithology (1831) and Dugald Stewart’s Collected Works in 11 volumes (1854-60). After Thomas sold out his stock in 1860 to devote himself to writing, his son Archibald formed a new publishing company, which identified itself until about 1890 as T. & A. Constable. By 1891, ten years after Thomas’s death, the firm had relocated to London and appears on the title-pages of the books it published as “Westminster: A. Constable” or “Westminster: Archibald Constable and Co.” The new firm continued along the path followed by Thomas Constable, but was far more active than the latter had been in recruiting poets, dramatists, novelists, and artists. Among the books published by A. Constable and Co.: George Meredith’s The Amazing Marriage (1895), Alice Meynell’s London Impressons (1898), George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman (1903) and The Doctor’s Dilemma (1911), George Gissing’s The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903), the poet Laurence Binyon’s verse play Paris and Oenone (1906), Arthur Symons’ William Blake (1907), Hilaire Belloc’s On Anything (1910), and Through China with a Camera , with over 100 illustrations by the celebrated Scottish photographer John Thomson (1898), not to mention Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). Set up in 1910, the renamed firm of Constable and Co. published the popular poet Walter De la Mare’s A Child’s Day and The Listeners and other poems (1912), followed by Peacock Pie (1913) and four other books of poems, Katherine Mansfield’s The Garden Party and other stories (1922), along with additional collections of her short stories and two volumes of her poems (1923 and 1924), and essays by the provocative writer on sexuality, Havelock Ellis (Impressions and Comments [1921], The Dance of Life [1923]). The Scottish connection of the great publishing firm had been severed, however. Constable, in Edinburgh, survived only as a printer.

Spreading the Word: Scottish Publishers and English Literature 1750-1900

- Scotland and the Modern World: Literacy and Libraries

- Scottish Publishers, London Booksellers, and Copyright Law

- Andrew Millar (London) 1728

- William Strahan (London) 1738

- Robert and Andrew Foulis, The Foulis Press (Glasgow) 1741

- John Murray (London) 1768

- Bell & Bradfute (Edinburgh) 1778

- Archibald Constable (Edinburgh) 1798

- Thomas Nelson and Sons (Edinburgh) 1798

- John Ballantyne (Edinburgh) 1808

- William Blackwood (Edinburgh) 1810

- Smith, Elder & Co. (London) 1816

- William Collins (Glasgow) 1819

- Blackie and Son (Glasgow) 1831

- W.& R. Chambers (Edinburgh) 1832

- Macmillan (Cambridge and London) 1843

- Lesser Publishers

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-century British Copyright Law: A Bibliography

Bibliography

Altick, Richard. The English Common Reader. A Social History of The Mass Reading Public 1800— 1900. 2nd ed. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1998. (1st. ed. University of Chicago Press, 1957).

Constable, Thomas. Archibald Constable and his Literary Correspondents. 3 vols. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1873.

Feminist Companion to Literature in English. Ed. Virginia Blair, Patricia Clements, and Isobel Grundy London: Batsford, 1990.

“Financial Hardship.” Walter Scott. Web. 25 September 2018.

Garside, Peter. “Mrs. Ross and Elizabeth B. Lester; New Attributions.” Available on the University of Cardiff website.

Low, D. A. “Publishing in the Eighteenth, Nineteenth and Mid-Twentieth Centuries” in The New Companion to Scottish Culture. Ed. David Daiches. Edinburgh: Polygon, 1993, on p. 258. See also Richard D. Altick, The English Common Reader

MacKenzie, Raymond R. “Archibald Constable and Company” in The British Literary Book Trade 1700-1820. Ed. James K. Bracken and Joel Silver. The Dictionary of Literary Biography vol. 154. Detroit: Gale Research, 1995.

Macleod, R.D. The Scottish Publishing Houses. Glasgow: W. & R. Holmes, 1953.

Timperley, C.H. A Dictionary of Printers and Printing. London: H. Johnson, 1839.

Last modified 19 October 2018