eorge Vicat Cole (1833-1893) was born in Portsmouth, the son of an artist. His father, George Cole (1810-1884) had begun his career as a self-taught animal painter and from 1838 began his climb to fame with shows at several London galleries. These were largely landscapes but also portraits, animal paintings and still lives, showing the influence of Dutch painters. The young Vicat Cole grew up in an atmosphere of eclectic artistic striving and was soon showing talent himself. He had no formal artistic training - something he later regretted - but was tutored by his father whom he accompanied on several sketching tours to well known English beauty spots and also abroad in the Moselle region. His earliest work was shown at the Society of British Artists in 1852, shortly before his nineteenth birthday.

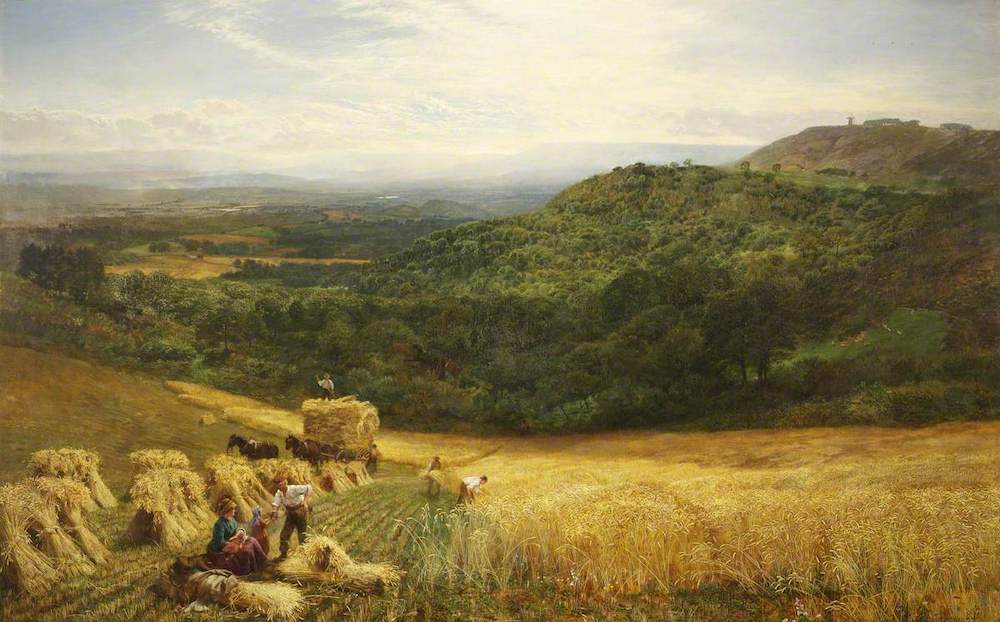

The Cole family moved to Fulham, London, in October 1852 where George Cole began his ascent into the higher reaches of the artistic fraternity. His son also had his first successes with pictures exhibited at the British Institution and the Society of British Artists, and in 1853 two pictures accepted for the Royal Academy. However Vicat Cole quarrelled with his father in 1855 and the two parted company, with the younger George moving to Camden Town in north London. Here he married Mary Anne Chignell and the couple began a ‘time of uphill arduous struggle’, according to Vicat Cole’s brother-in-law, Robert Chignell, who published a posthumous biography. Vicat Cole continued to sketch outdoors, spending the summers of 1857-1859 in the Surrey village of Albury where he formed a friendship with another landscape artist, Benjamin Williams Leader (1831-1923). The surrounding landscape was much to the liking of the young artists and Vicat Cole returned to it many times during his career. Harvest Time, awarded the silver medal of the Society for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in 1860, was his first major success and was sold for £120.

Harvest Time (1860). Credit: @ Bristol Culture: Bristol Museum & Art Gallery.

Vicat Cole’s financial position had improved during the 1850s although he was disappointed at the reaction from the Royal Academy which either rejected his pictures or hung them badly. However the Society of British Artists continued to support him and at the end of the decade he moved into 19 Gloucester Road, Kensington. This was on Campden Hill, by now a very popular haunt of artists, and he made several friends in the district, rescuing some pictures from a fire at Augustus Egg’s studio in the house opposite which was then known as The Elms.

Vicat Cole was influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, a group of artists only a few years older than he was, who advocated painting out of doors, using brilliant colour with a minimum of shadow and close observation of every minute detail. Like them he had noted Ruskin’s instruction to ‘....go to Nature in all singleness of heart.... rejecting nothing, selecting nothing and scorning nothing....rejoicing always in the truth.‘ Having absorbed this dictum Vicat Cole sent his work Spring to the RA in 1865 where it was championed by John Everett Millais, then on the hanging committee, who insisted that instead of being ‘skied’ it was hung at eye level.

Springtime (1865). Credit: Manchester City Gallery. This is the title given to the work here, perhaps to prevent confusion with another picture called Spring, also painted in 1865, currently at Portsmouth Art Gallery).

This was a turning point in Vicat Cole’s career at a time when landscape artists were receiving little support from the establishment and were consequently less well remunerated, their prices well below that of successful portraitists. Vicat Cole was now able to increase his prices and by 1868 had moved into 8 Victoria Road, an artistic enclave south of Kensington High Street. In 1870 he was elected Associate of the RA, which at once brought him an even higher level of status and income. This prompted another move in 1874 to Little Campden House, formerly known as The Elms. By now he had a family of three daughters and a son; this handsome capacious Queen Anne building with its large walled garden was their home until 1893.

The Heart of Surrey (1874). Credit: Manchester Art Gallery.

During the 1870s Vicat Cole’s work, mostly of the Surrey countryside, sold well and he was elected a full Academician in 1880. After this he changed course and during the last thirteen years of his life devoted himself to a new project, financed by his dealer Agnew, to paint a series of views of the river Thames from its source to the sea. He was very fond of this river and purchased a boat to help him find the locations for his pictures. According to The World, his steam launch was ‘....often to be seen anchored in various parts of the Thames, sometimes for weeks altogether, which used to excite the curiosity of the river’s traffic by the apparently singular inactivity of its occupant, until it gradually became known as the locomotive studio of Mr Vicat Cole’ (6).

Cole used his boat for pleasure trips as well and often invited his friends for outings and picnics. Among these were the painters Frederic Leighton, W.W Ouless, H. Stacy Marks, George Boughton and G.D. Leslie, as well as the Punch cartoonists George Du Maurier and Linley Sambourne.

Left: Iffley Mill (1884). Credit: Towneley Hall Art Gallery. Right: Pool of London (1888). Credit: Tate Gallery.

Richmond Hill had been painted before the idea of a Thames series was conceived and shows a view already made famous by Turner. Cole now began to paint less well known vistas, beginning with the upper reaches of the river near Oxford. Iffley Mill, exhibited in 1884, was clearly influenced by Constable. It is interesting to compare it with the landscapes of Cole’s friend and rival, Benjamin Leader, who was also financed by Agnew and regularly exhibited river paintings to high acclaim.

Quite different in style and most striking of all Cole’s Thames paintings was The Pool of London, on a canvas ten feet wide and six feet high. This jumble of shipping on a choppy river under stormy skies was not at all like the pastoral scenes the public associated with him and it caused a sensation when exhibited in 1888. It was selected for the Chantrey Bequest and the price, £2000, was the highest Cole ever received and was among the largest sums ever paid for a Chantrey purchase. Although there were criticisms, most notably from the Athenaeum who dismissed it as a work unworthy of patronage, many people, including Gladstone, were very impressed by this celebration of commerce on a grand scale.

Westminster, exhibited in 1892, was the last of Cole’s paintings in the Thames series. According to his biographer, T.J. Barringer,

There is a valedictory suggestion in the choice of evening sunlight as an atmospheric effect for Westminster. Here the nationalistic theme was more apparent than in any other of the Thames paintings: Cole had chosen to depict a scene whose principal feature, rising between the river and Westminster Abbey, was the Palace of Westminster, the Victorian rebuilding of which formed a major event in British history. Westminster stood as a visible symbol of the marriage of values of Parliamentary democracy, constitutional monarchy and hereditary nobility held so dearly by the Victorian middle class. [100]

Westminster (1892), Guildhall Art Gallery.

These days we are so familiar with this image that we may reject the painting as hackneyed; it did not seem so when first seen and was a great success with the public.

George Vicat Cole died on 7 April 1893 aged 59, ten days short of his sixtieth birthday. This seems young today, but not many Victorians could expect to live beyond their seventieth birthday. Leighton died aged 66, Millais 67, Rossetti 54. Leighton paid a tribute to Cole in his Academy dinner speech two months after Cole’s death, specifically mentioning the Thames series, when he himself had only three more years to live.

After Vicat Cole’s death in 1893 a studio sale was held of his remaining paintings and sketches. These fetched poor prices. The decline of public interest in Victorian art was just beginning, but was to accelerate after Leighton’s death in 1896 and ever faster as the end of the century approached. Vicat Cole’s contemporary Benjamin Leader lived long enough to see his work suffer total eclipse; fortunately for Vicat Cole he did not witness this seismic change. Being among the highest earners in the landscape fraternity he died a wealthy man, leaving behind a widow, three unmarried daughter and a son, Rex Vicat Cole, who also became a landscape painter. The family moved out of Little Campden House to 9 Campden Hill Square and later Rex built his own small house and studio in the rear garden, 9 Hillsleigh Road. His son, John Cole, continued the family tradition of landscape painting.

Works

Bibliography

Barringer, T.J. The Cole Family, Painters of the English Landscape, 1838 -1975. Portsmouth City Museums, 1988.

"Celebrities at Home, Mr Vicat Cole at Little Campden house, Kensington." The World. 6 May 1885.

Chignell, Robert. The Life and Painting of Vicat Cole RA. 3 vols. London: Cassell, 1896. (All three vols. available on the Internet Archive, digitised from copies in the Getty Research Institute.)

Created 29 September 2022