This is an expanded version of a review originally published in the Times Literary Supplement of 24 July 2020. Apart from the first and last, the accompanying photographs are from our own website. Click on the others for larger pictures and additional information.

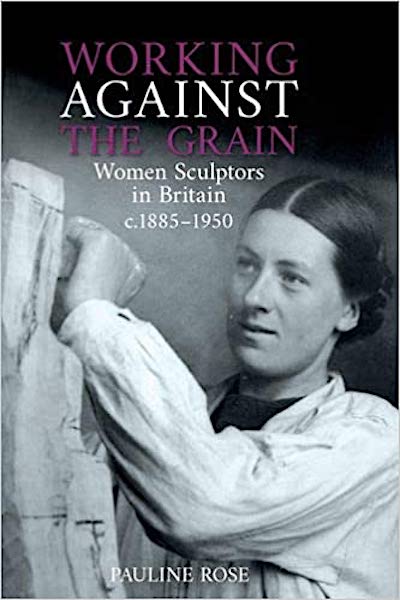

Cover of the book under review, showing Mary Spencer Watson carving, c. 1935.

Pauline Rose's Working Against the Grain deals with a key period in the history of sculpture, a time of cross-fertilisation between the Arts and Crafts Movement and the New Sculpture, when modernism itself was emerging. The late nineteenth century was also a time when a whole cohort of women first entered professional training. Rose does full justice to all this in her excellent second chapter, “Context.” In particular she advocates recognising the "artistic interconnections and overlaps" of these years (19), rather than imposing neat and therefore limiting categories on the different kinds of work that came out of them. This allows her to look at individual oeuvres in the round, something especially helpful when dealing with the young women now learning new skills and developing their own styles.

Earlier Women Sculptors

Left to right: (a) Susan Durant's marble relief medallion of Princess Louise, c. 1866. (b) Mary Thornycroft's depiction of the infant Princess Beatrice, The Cradle, 1858. (c) Figures around the central doorway in the West Front of Lichfield Cathedral, Staffordshire, by Mary Grant, 1876-84.

These women were not pioneers. Susan Durant had completed her over-life-size marble Faithful Shepherdess for London’s Mansion House in 1863; Mary Thornycroft, who replaced Durant as tutor to Queen Victoria’s artistically gifted fourth daughter, Princess Louise, is richly represented in the Royal Collection; and in Scotland, Amelia Hill, née Paton, contributed three figures to the Scott Monument on Princes Street, Edinburgh, later winning acclaim in 1876 for her statue of David Livingstone nearby. Another talented Scottish sculptor, Mary Grant, continued to practice into the new century. It seems a shame that no space is given to these women, even by way of introduction. Rose mentions only Durant and Thornycroft, and then only in connection with their tutoring of Queen Victoria's fourth daughter, Princess Louise. But this is exactly Rose's point: Thornycroft was instrumental in furthering her pupil's formal training, so that the princess could attend the National Art Training School — "one of Prince Albert's innovations," Rose points out (158). This was in 1868. From now on, it would not be a case of the exceptional few. Doors would begin to open to any talented woman spirited enough to enter the predominantly male world of professional work.

The New Women Sculptors

Views of the competition model of The Spirit of the Crusades, by Gertrude Alice Meredith Williams, 1922, at the Amgueddfa Cymru Caerdydd [National Museum of Wales, Cardiff]

Louise herself was part of what Spielmann called this new "bevy of fair sculptresses" (qtd. in Rose 1). Unfortunately, the queen's initial reluctance to let her daughter move forward like this proved well-founded: people gossiped about the princess's relationship with her tutor, Edgar Boehm, who died unexpectedly while she was in his studio. Probably as a result of this, Rose, like Louise's biographer Lucinda Hawksley, found it impossible to penetrate the official secrecy surrounding this royal figure. But for other young women, too, the serious study of sculpture was still a bold choice, and Rose found it hard to gather information about even the most skilful of them. The unveiling of the Paisley War Memorial provides a startling example of how they were apt to be passed over. Called The Spirit of the Crusaders, the sculpture group comprises a knight on horseback, pennant fluttering, with four soldiers trudging along beside him in heavy World War I greatcoats. The sense of dogged, unshakeable purpose is palpable. It is a major achievement by any standards. The contemporary press, Rose tells us, assumed that the sculptor of such a powerful monument was a man, and identified "him" accordingly (239). The first photograph in the book is the ideal riposte: here is Gertrude Alice Meredith Williams, dwarfed by the plaster-cast of the sculpture, dressed in her white sculptor's smock and leaning back on its base with a proprietary air.

Left to right: Margaret Giles's Hero, 1901. (b) Ruby Levick's Rugby Football, 1901. (c) Kathleen Scott's Robert Falcon Scott, 1915.

There will be no excuse for wrong assumptions now: Rose’s study reveals the full scale of women’s involvement in every kind of sculpture from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century — from modelled to carved, allegorical to representational, monumental to decorative, and architectural to ecclesiastical, all in a variety of materials. Apart from Williams, Rose's chosen era produced (amomgst others) Margaret Giles, whose nude female statuette, Hero, seen on the right above, challenges the presumption of gentle, vulnerable femininity, and Ruby Levick, another award-winning sculptor who exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, and whose groups of boys engaged in sports like wrestling and football confirm women sculptors’ versatility. Kathleen Scott, widow of Captain Scott of the Antarctic, was another who preferred male sitters, including such notables as George V and Neville Chamberlain, both for ideal and portrait work.

Panel in the Children's Corner by Ellen Mary Rope (1855-1934). Painted plaster. St. Margaret's Church, Leiston, Suffolk.

Several others stand out from the "bevy," including Violet Pinwill (1874-1957), whose exquisite ecclesiastical wood-carving is to be found in over two hundred churches in Devon and Cornwall (252). The Arts and Crafts movement had its most obvious crossover here, and in the Della Robbia work of Ellen Mary Rope: "The boundaries between fine and applied art appear to have been surprisingly porous in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century," remarks Rose (11). These women were far from being hobbyists: Pinwill's sculptural work was inseparable from her business life, She ran the firm of V. Pinwill Carver for nearly fifty years. Rope, who was enthusiastic about working with architects, proved to be "commercially adept, and able to manoeuvre her career in directions responsive to the marketplace" (115-16). Among her exhibits at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society were designs for ceiling and wall panels, and even a tea caddy (215). Like Mary Spencer Watson (1913-2006), featured on Rose's front cover, these were every inch professionals. Women were no longer simply on the fringes; they were showing their work, taking commissions, employing others, and setting trends. One indication of this is that many, besides Williams, were responsible for war memorials: Rosamund Praeger (1867-1954) alone completed more than ten (236).

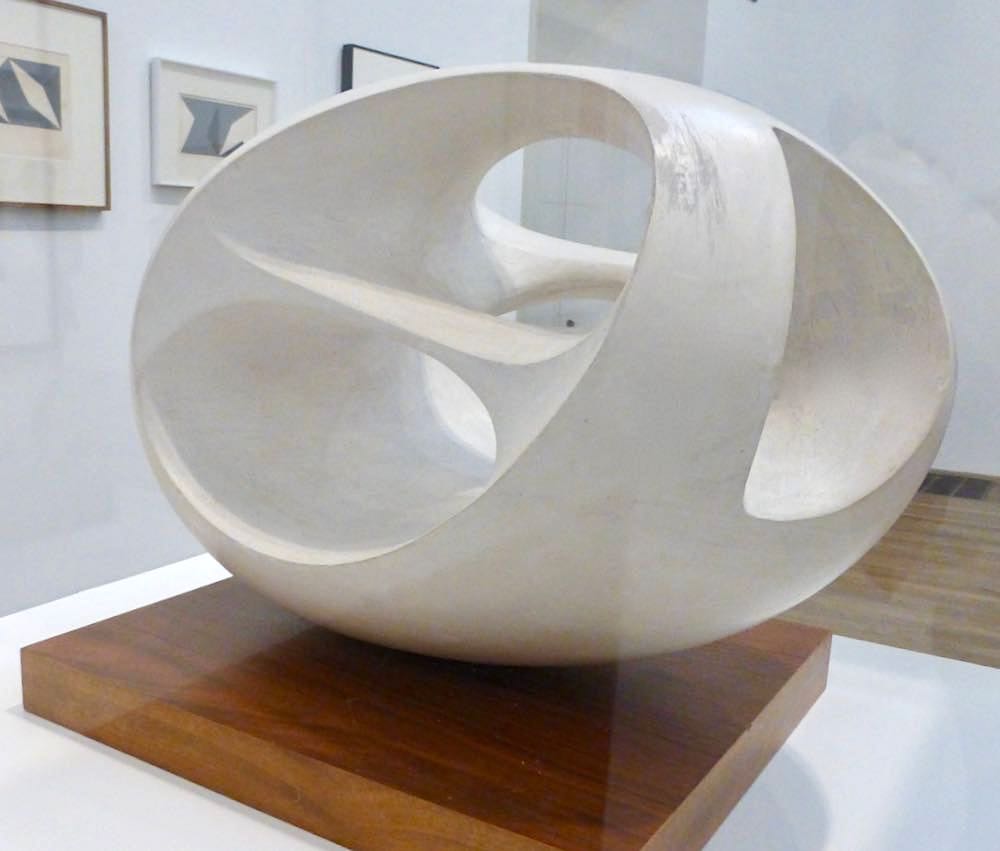

Barbara Hepworth's Oval Sculpture (No. 2), 1943, cast 1958, plaster on a wooden base; present author's photograph taken at the Tate Modern.

Women's progress, in this as in other spheres of life, was hard won: it is worth remembering that the Royal Academy Schools had denied them access to its life room right up until the 1890s (29). However, by the end of the period, many factors, from photography to the popularity of statuettes, had allowed them to display their work to a wider public. Moreover, the sculpture exhibitions, held first at Heal’s furniture store in Tottenham Court Road in 1945, had brought examples of it right into the domestic sphere. “I have never felt that sculpture was too formidable to live with,” said Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975) in 1947 (qtd. in Rose 49). While discussing such developments, Rose throws light on Hepworth herself, and many others, in this carefully researched, revealing and beautifully illustrated study. Up until now, despite their numbers, most of these women have been largely forgotten, their career paths unexplored, their ouveres not well understood, and their praises seldom sung. Rose's book should help to change all this. It is heartening to know that it will soon be followed by another one, by Helen Wilson, exploring Pinwill's achievements (due out in January 2021).

Related Material

- Victorian and Edwardian Women Sculptors

- Zoë Thomas's Women Art Workers and the Arts and Crafts Movement [Review]

- Victorian Women and the Visual Arts

Bibliography

(Book under review) Rose, Pauline. Working Against the Grain: Women Sculptors in Britain c. 1885-1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020. Hardcover, £30.00. ISBN 978 1 78962 156 3.

Created 7 December 2020