ueen Victoria's coronation took place on June 28th. 1838, almost exactly a year after she had succeeded to the throne at the death of her uncle, William IV. As with every important occasion throughout her life, the Queen recorded the events of this day in meticulous detail in her Journal, begining as usual with the time at which she awoke —

'Thursday, 28th June! — I was awoke at four o'clock by the guns in the Park, and could not get much sleep afterwards on account of the noise of the people, bands, &c., &x. Got up at 7 ... At Vz p. 9 I went into the next room dressed exactly in my House of Lords costume [the heavy robe worn for the state visit to the House of Lords on July 17th 1837] ... At 101 got into the State Coach with the Duchess of Sutherland and Lord Albermarle and we began our Progress.'

There follows a long account of the whole day until the Queen retired to bed at midnight. The woefully under-rehearsed ceremony that followed the Queen's arrival at Westminister Abbey was not without its uneasy moments, but there can be no doubt of the impression that this historic occasion made on both the Queen and her assembled subjects in spite of the disenchanted tone taken by Greville in the record of the events of the day made for his Memoirs —

'June 29th — The Coronation (which, thank God, is over) went off very well. The day was fine without heat or rain - the innumerable multitude which thronged the streets orderly and satisfied. The appearance of the Abbey was beautiful, particularly the benches of the Peeresses, who were blazing with diamonds. . . The Queen looked very diminutive, and the effect of the procession itself was spoilt by being too crowded;. . . The different actors in the ceremonial were very imperfect in their parts, and had neglected to rehearse them. Lord John Thynne, who officiated for the Dean of [15/17] except the Archbishop and himself (who had rehearsed), Lord Willoughby (who is experienced in these matters), and the Duke of Wellington, and consequently there was a continual difficulty and embarrasment, and the Queen never knew what she was to do next . . . She said to John Thynne, "Pray tell me what I am to do, for they don't know;" and at the end when the orb was put into her hand, she said to him, "What do I do with it?" "Your Majesty is to carry it, if you please, in your hand." "Am I?" she said "It is very heavy." The ruby ring was made for her little finger instead of the fourth, on which the rubric prescribes that it should be put. When the Archbishop was to put it on, she extended the former, but she said it must go on the latter. She said it was too small, and she could not get it on. He said it was right to put it there, and, as he insisted, she yielded, but had first to take off her other rings, and then this was forced on, but it hurt very much, and as soon as the ceremony was over she was obliged to bathe her finger in ice water to get it off. [This lamentable accident may have been, in part, the fault of the Duchess of Kent who had presented her daughter with this ring to replace the large ruby and sapphire ring made 1 or the coronation of William IV.] The noise and confusion were very great when the medals were thrown about by Lord Surrey, everybody scrambling with all their might and main to get them, and none more vigorously than the Maids of Honour. [Presumably the Coronation medal designed by Benedetto Pistrucci and made by the Crown Jewellers, Rundell and Bridge] ... In the evening I met Prince Esterhazy, and asked him what the foreigners thought. He replied that they admired it all very much: "Strogonoff and the others don't like you, but they feel it, and it makes a great impression on them; in fact nothing can be seen like it in any other country".'

The nineteen-year-old Queen, literally weighed down by the heavy orb and the five pound weight of the crown that she told Lord Melbourne hurt her 'a good deal', began her reign which was to last until the turn of the century and to embrace a vast range of fashions and styles in jewellery which are all technically 'Victorian'.

The jewellery worn by the Queen at her coronation is shown in a study by the American artist Thomas Sully (see left column) for his [17/18] picture Queen Victoria Ascending the Throne (1838). The Queen's subjects were to become familiar with her appearance in the diamond circlet that she is wearing in Sully's sketch. Formed of crosses patée alternating with roses, thistles and shamrocks, it was designed for the coronation of George IV, and is worn by the Queen in the profile portrait on the first postage stamps.

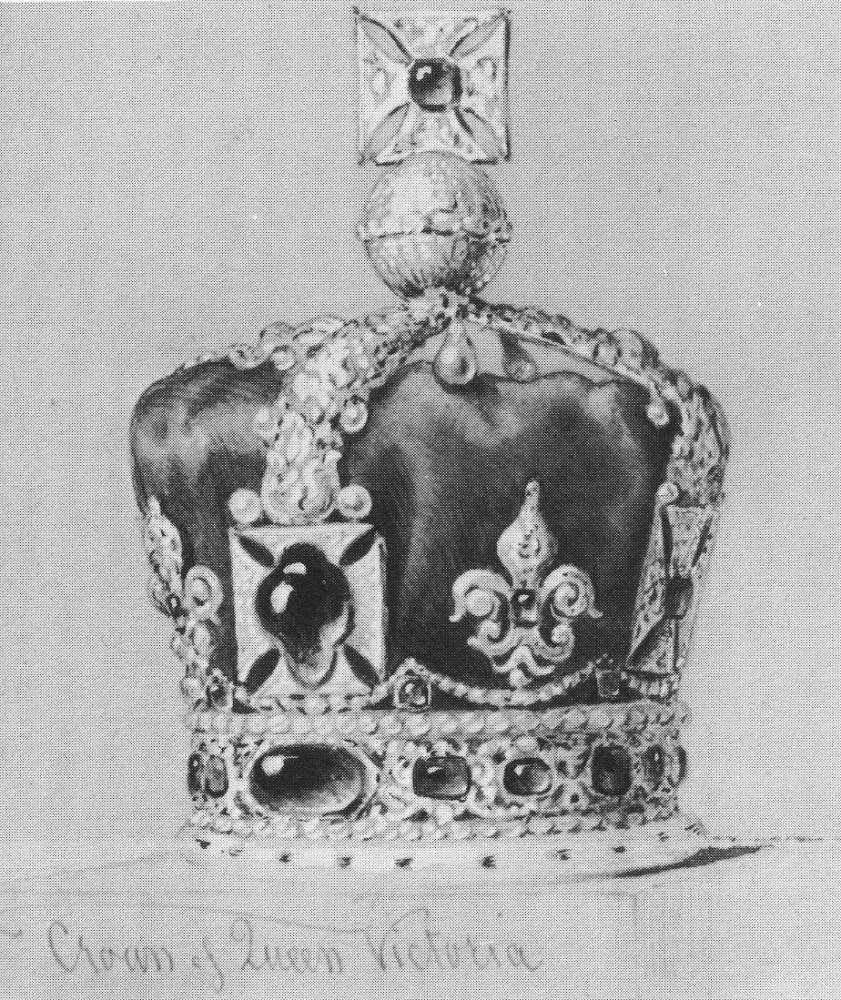

The crown and sceptre (see left column) which appear in the state portrait of the Queen in coronation robes, painted by Sir George Hayter, were drawn while they were still on the premises of the Crown Jewellers, Messrs. Rundell and Bridge, by Edmund Parris, who was Historical Painter to Queen Adelaide (plate 3b). Parris later made a drawiii" of the Queen in her coronation robes which was reproduced in the Connoisseur in 1902, as one of a series of 'Historical Costume Drawings', accompanied by the following note:

The crown was sketched at Messrs. Rundell and Bridge's (Crown Jewellers by Appointment), where it was made, and afterwards broken up. It was formed of gold, nearly covered with pearls and precious stones, amongst them the rock ruby of Edward the Black Prince and Henry the Fifth of Agincourt, and the great sapphire, two inches long by one inch broad'.

The Coronation jewels, even the crown which was made for this occasion, are basically Charles II in design, the time at which they were remade after being broken up and delivered to the mint during Cromwell's protectorate. Queen Adelaide's small crown, worn before her by Queen Charlotte and Queen Caroline, was dismantled and the stones were used in the new Imperial State Crown, the Stuart sapphire was set in the front part of the crown and Edward the Confessor's sapphire in the cross patee on the top.

Miniature portrait of Queen Victoria' by William Plant, after Sir George Hayter, 1841. Set as a brooch in a surround of diamonds and opals and enamel. Given by the Queen to Viscountess Jocelyn, who had been one of the train-bearers at the coronation and at the Queen's marriage in 1840. Inscribed 'To the Viscountess Jocelyn from Victoria R. April 27th 1841.

Queen Victoria's liking for miniatures and sentimental jewellery of all kinds is reflected in Victorian taste; from the time of her marriage she herself always wore a miniature of Prince Albert set in a bracelet, and she frequently gave miniature portraits of herself and the Prince as presents, such as the ones which she gave to her Scottish servant, John Brown (London Museum) set in the gold locket which also contained locks of hair. A miniature by Sir George Hayter surrounded by opals and diamonds set in enamelled gold was given by her to Lady Frances Cowper, a [19/20] trainbearer at the coronation and at the Queen's marriage and later an extra lady-of-the-bedchamber, eighteen days after her marriage to Viscount Jocelyn; it is inscribed on the reverse To the Viscountess Jocelyn from Victoria R, April 27th 1841'. The bridesmaids at the Queen's marriage were given a turquoise eagle holding a single pearl in its claws, mounted as a brooch. The Queen herself wore a large sapphire, bordered by twelve large diamonds which was given to her by Prince Albert, for the wedding ceremony which she described, like every other event of any significance in her life, in her journal:

'. . . At 1/2 p. 12 I set off, dearest Albert i.;.,^^ gone before, I wore a white satin gown with a very deep flounce of Honiton lace, imitation of old. I wore my Turkish diamond necklace and earrings, and Albert's beautiful sapphire brooch.'

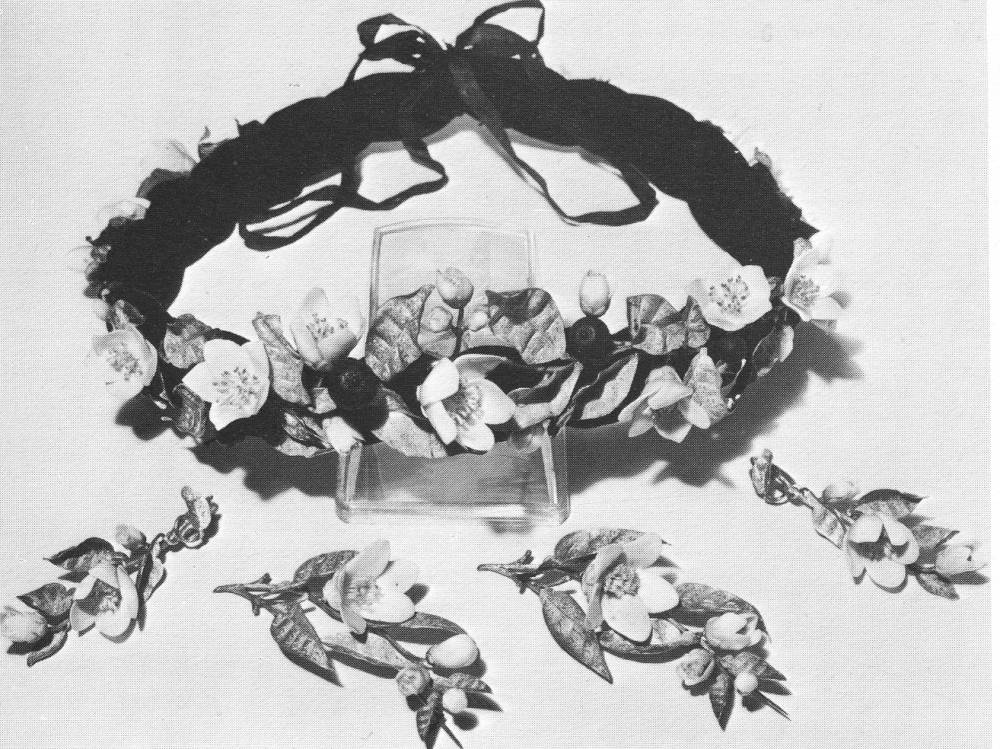

A note following this passage from the Queen's journal which was quoted in The Girlhood of Queen Victoria records the information that the diamond necklace was left to the Duke of Connaught and the sapphire brooch to the Crown. The Queen's head-dress for this occasion was a wreath of orange blossom, which inspired Prince Albert to design a set of jewellery consisting of a wreath, which he gave to her on the anniversary of their wedding, February 10th, in 1846, and a brooch and earrings which he had already given her for Christmas in 1845. The set, made of white porcelain, green enamel and frosted gold, the stamens in the flowers being made of threads of porcelain, is almost unbearably delicate and feels as if it might collapse at a touch but has survived for 125 years (plate 4a; see left column). Fortunately the Queen was very fond of jewellery, an essential taste in Royalty, as she was to receive a considerable number of jewels as presents and official offerings throughout her long reign, as did the wives of her son and grandson, Queen Alexandra and Queen Mary. Soon after her marriage in 1893 Queen Mary wrote to her mother from Osborne describing the dresses and jewellery worn by her at two dinners, including the 'Iveagh's tiara', a necklace which came from her Grandmother, the 'Kensington bow', the 'Warwick's sun', the 'combined counties pearls' and the 'Richmond's pearl and diamond brooch'.* Many of these gifts were of great value, like the Indian jewellery presented to the Queen by the East India Company after the closing of the Great Exhibition in 1851 (p. 64), but the design of one or two of the pieces was somewhat bizarre, as, for instance, the diamond brooch in the shape of the entrance to the Mersey Tunnel which was presented to her by the Liverpool Corporation when she opened the tunnel in 1857. This gift would not have been unappreciated by the Queen; : had a taste for commemorative jewellery of all kinds. She herself was prepared to take a considerable amount of trouble with the design of the Jewels which she had made to mark the various Royal occasions as can be seen from the following letter from Osborne, dated 9th February 1888, preserved in the Scrapbook of G. Whitford of Messrs. Garrard, Jewellers 1857-1891, now in the Royal Library at Windsor, which contains designs for jewellery, correspondence, and even a lock of Queen Alexandra's hair in an envelope:

Miss Dettweiler returns Messrs. Garrard and Co. the enclosed sketch. Her Majesty wishes the shape a little altered, but otherwise quite approves 'of it. It is to be in shape more like the Queen's brooch which Miss Dettweiler showed to Mr Whitford. The sketch is too straight and Her Majesty wishes the brooch also to be a little shorter & the least broader.

Bracelet designed for the marriage of the Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra. 1863. From the Scrapbook of G. Whitford.

The three alternative designs for a bracelet to be made for the marriage of the Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra have pencilled alterations made by Princess Alice, presumably at the suggestion of the Queen, mostly changes in the proportion of the designs (see directly above).

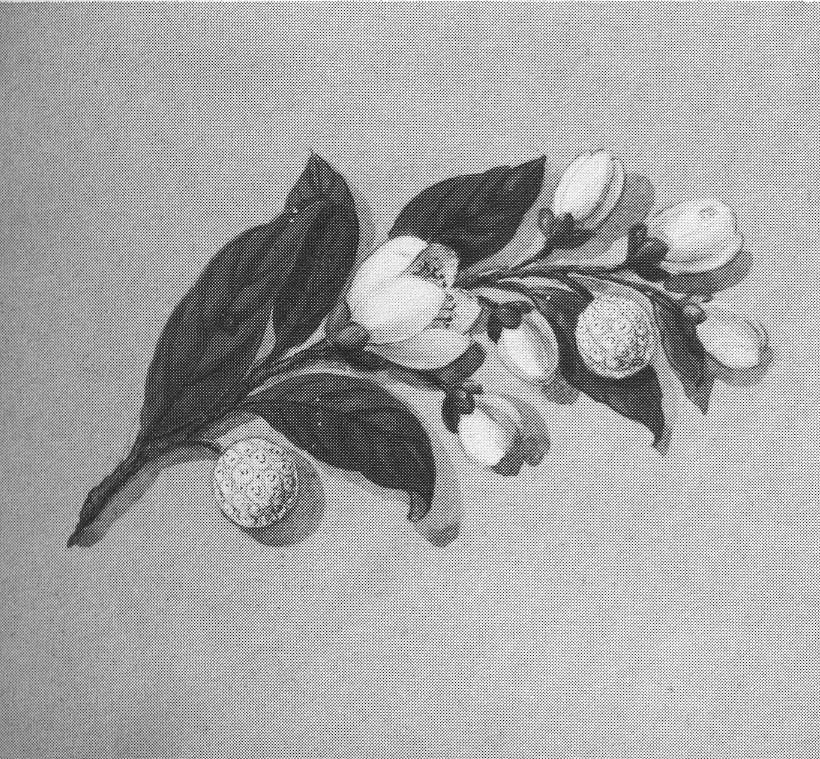

Spray of orange blossom with oranges of decorated gold. 'Painted by the Queen Victoria'. This painting comes from the Scrapbook assembled by G. Whitford who worked for Messrs. Garrard from 1857-1891. It suggests that the Queen had a hand in the design of the set of jewellery illustrated in plate 4a.

Scraps of paper with pencilled suggestions for the outline of a brooch or bracelet, unfortunately very vague, made by the Queen for the guidance of Mr Whitford in the execution of some commission, are also preserved in this book, and the painting of the spray of orange blossom (right) which is stuck onto a page amongst the letters and. bracelet designs suggests some collaboration with Prince Albert over the design of the gold and porcelain set of jewellery described above.

Queen Victoria's taste in jewellery is typical of the period, though rather modest in comparison with the Imperial preferences of the Empress Eugenie (plate. 27) and the French Court at the time of the Second Empire or Empress Elizabeth of Austria, but it gives only the barest indication of the wide range of possibilities which were to be explored during the century. [22/24] In making even the most cursory study of jewellery design since the time of the great classical civilisations of Greece and Rome one thing becomes apparent; not, as might have been expected, that great developments have taken place, but that, throughout the years, very little has altered in the basic conception of how jewellery should look, and that even the changes in surface ornament are fairly superficial. It almost seems as if the form which jewellery should take was finally decided at the time of the Italian renaissance. The way in which jewellery is worn, (which in Western civilisation has also changed hardly at all, none of the recurring passions for Eastern dress and-jewellery ever led to its being used to produce the grotesque physical distortions which are found in some primitive cultures), is bound to inhibit any very radical development of the basic shape, and though considerable changes in the design took place within the bounds imposed by convenience, certain conventions of ornament were nearly always respected right up until the closing years of the century. The nineteenth century is regarded as a period of lavish display when people seem not to have been inhibited by any petty considerations of 'good taste' in the embellishment of their houses or their persons, a state of things that was later to disgust William Morris and his Aesthetic followers, but the fact remains that both men and children who heretofor had worn a certain amount of jewellery as a matter of course now wore practically none at all, and from 1850 onwards very little jewellery was worn even by women during the day. But these minor changes in fashion did little to affect the situation and even the two major developments in the jewellery trade of the nineteenth century did very little to alter these conventions of shape and decoration. Neither the extensive mechanisation which took place throughout the trade, nor the almost complete breakdown of recognisable regional styles in Europe at least, the improved communications and the exchange of ideas which resulted from the large International Exhibitions had the effect of 'Europeanising' jewellery design to a very marked extent), had any very great influence on jewellery design. Mechanisation, at least, was seen as a way to facilitate the production of decorative work hitherto carried out by hand, and it is only with the revival of handcraftsmanship at the turn of the century that the pieces of jewellery which were conceived as a [24/26] work of art rather than as fashionable accessories, which often made them difficult or unsuitable to wear, achieved some sort of break-through in design. In spite of this there is no mistaking the Victorian style, or styles. A number of different influences contributed to the formation of this style. Certain interests such as the cultivation of rare plant species which was enthusiastically taken up in this country and in France during the nineteenth century, and the wide public interest in archeology and the decorative art of the past, had their effect on jewellery design, but 'fashions' in dress and decoration, the preferences of the Court and the aristocracy, determined the shape of most of the jewellery produced during almost the entire period, this conventional view of jewellery only being abandoned at the turn of the century. It is interesting to trace, where possible, the source of the designs which commonly occur in Victorian jewellery, especially since so many of the developments of this period have contributed to the form of modern jewellery, and to an even greater extent, to the materials which are used nowadays.

The field of fashion in the nineteenth century has been so extensively surveyed that no nuance of shape in bustle or crinoline remains unrecorded; inevitably the design of jewellery is affected by changing fashions of dress and coiffure, the radical changes in the shape and proportions of dresses during the first forty years of the nineteenth century being reflected in the jewellery design of the period. The Gothic jewellery of the 1840s has no place on the [26/27] flimsy classical dresses fashionable at the turn of the century, nor could these have supported the weight of the ornate jewels which were so well suited to the more extravagant and cumbersome styles of the Victorians. Though it is unlikely that all the niceties of proportion and historical accuracy were always considered by the designers or purchasers of brooches and bracelets or other fashionable bibelots, the study of modes and manners can provide some sort of a rough guide to the date of a piece of jewellery.

In spite of the improvement in communications during the nineteenth century the time-lag in fashion between, for instance, Paris and London, or between a capital city and the provinces, was [27/28] The eighteenth century tradition of Adam-style classical decoration dominated English design until the peace with France in 1814. The cessation of hostilities revealed the changes which had taken place in the French classical style, which was now dominated by the archeological taste of the defeated Emperor as interpreted by his architects Percier and Fontaine.

Plate 7a. Tiara of branch coral and coral beads c. 1850. Coral was fashionable in the first half of the Victorian period.

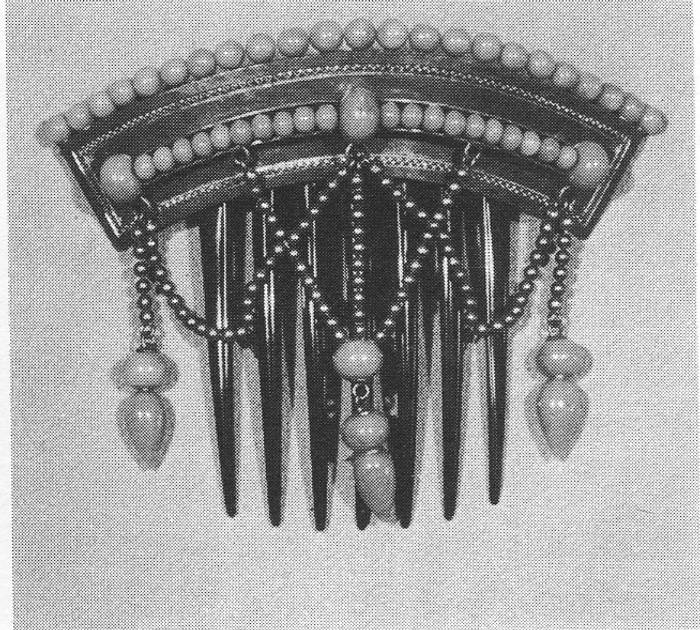

The archeological research carried on during and after Napoleon's campaigns in Egypt and Italy had a revolutionary effect on the styles taken from the antique which was to last throughout the nineteenth century fashionable jewellery of this period included the cameos pupularised by the Empress Josephine, linked by chains of gold or pearls to make necklaces, earrings and bracelets, and set in tiaras and decorative combs; gold filigree-work of great delicacy; coral (plates 7a & b); and mosaic jewellery with motifs taken from Pompeiian wall-paintings (plate. 7c) — the excavations at Pompeii had been re-opened on the orders of Napoleon at the end of the Italian campaign — and intricately worked gold chains of every description.

Left: Plate 7b. Comb decorated with coral beads. c. 1830-40. This type of comb is sometimes called a 'Josephine' or chignon comb. Right: Plate 7c. Earrings, mosaic and gold. Italian, c. 1860. The mosaic design is taken from the frescoes at Pompeii. These earrings were bought in Rome in 1860. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

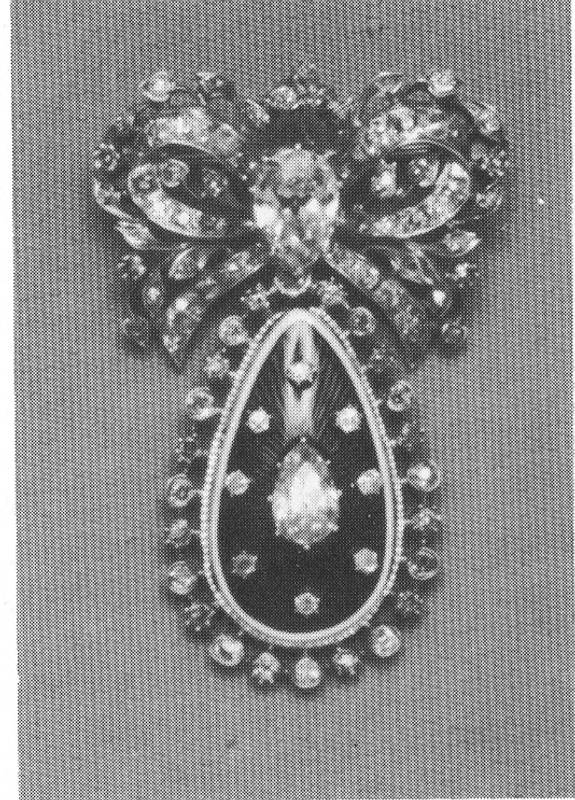

The design of most diamond jewellery was still in the eighteenth century tradition with rose-cut stones foil-backed iprove their colour, while many of the traditional pattern book designs, like those of Gilles Legare, the seventeenth century French designer, were used almost unaltered. This conservatism in the design of diamond jewellery which persisted throughout the nineteenth century is less surprising during the first twenty years than in later years, for until 1820 correct court dress was still the hooped brocade dress of the middle years of the previous century, and this formal and completely antiquated style was still de rigeur for the evening in certain old-fashioned country houses as well. The tendency to use diamonds and other valuable stones in a traditional way still persists to-day; a change in this habit might have been expected in the 1860s, when diamonds became relatively plentiful after the opening up of the South African diamond fields and during the two following decades when diamonds were considered the only possible material for jewellery, but the real break with the past was only finally achieved by the firm of Cartier in the years following the first World War. Improvements were made in the techniques of cutting and setting the stones which did much to alter the appearance of diamond [28/30] jewellery, but when these precious stones are used, either alone or combined with emeralds, rubies and sapphires, the designers seem to be attacked by the 'heirloom syndrome' and generally speaking innovations are avoided. But the new techniques in cutting and setting stones were enthusiastically adopted, so that even the diamond jewellery made in dclibrate imitiation of eighteenthcentury work has a greater brillir ice, sharpness and regularity which reveals its date.

The brilliant-cut, which was developed at the end of the seventeenth century, was only generally adopted during this period; and, except for a brief time at the end of the century when the rose-cut came back into fashion, it came to be regarded as the only way to do full justice to the stone. The fine paste jewellery of the early nineteenth century mostly tended to imitate the current styles in diamond jewellery in the same way as the glass attempted to imitate the stone. Since paste jewellery has no intrinsic value it does not suffer the almost inevitable fate of diamond jewellery, of being broken up and reset, and quite a large quantity of old paste jewellery still survives in good condition (Plate 1a) but unlike diamond jewellery, it is almost impossible to repair as the colour and worn condition of old paste cannot be matched.

Plate 1a. Decorative comb-mount, pinchbeck and paste. c. 1810-20. Courtesy of City Museum and Art Gallery, Birmingham. French. These comb-mounts or 'frontets' just pre-date the tiara as we know it.

Certain types of jewellery which had a functional purpose were immune to changes in fashion except in superficial ways. Chatelaines and combs, and brooch or pendant watches which were worn throughout the century, only reflected the current modes in their shape or ornamentation, saved by their usefulness from the fate which overtook earrings in the eighties, which were considered vulgar and not worn at all. Chatelaines, like ornamental combs, were made in every material from diamonds to steel, and it was only with the coming of the handbag and the abandonment of the 'keys' (the great status-symbol of the ruler of the household from mediaeval times until the final disappearance of household servants) that the chatelaine has fallen into disuse. Ornamental combs and elaborate hair ornaments were abandoned after the 1914-1918 war, with the long hair which they secured; the jewelled or enamelled watches which were sometimes part of the chatelaine or worn as pendants on chains or as brooches were only superseded by the wrist-watch at about the turn of the century (watches were first worn on a leather strap round the wrist in [30/31] 1888) though unlike the chatelaine or the ornamental comb they have returned to fashion in the twentieth century. The practical advantages of the wrist-watch are so great that it seems unlikely that it will ever be abandoned.

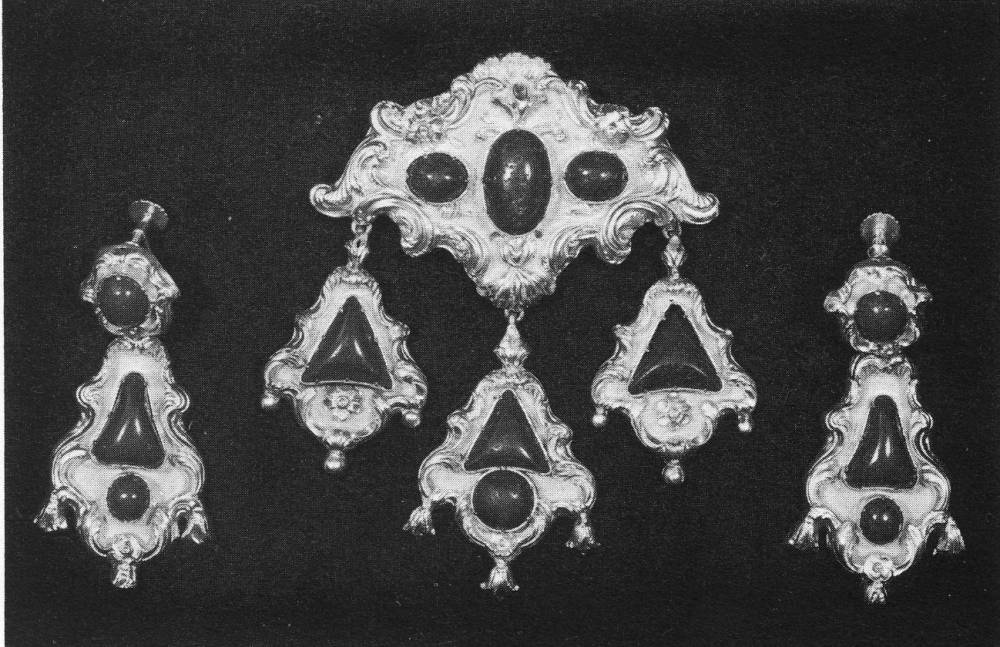

Plate 8. Demi-parure consisting of brooch and earrings. English c. 1850-60. Stamped gold set with porphyry. The appearance of substance is deceptive. Courtesy of the London Museum.

Some of these changes in jewellery fashions can be traced in the ladies' magazines of the period, though in the text rather than in the illustrations, for the jewels are so much subordinated to the necessary rendering of every knot and flounce on the dresses that fashion plates are not always as much help as they might be. The . earliest fashion magazines date from the end of the eighteenth century, and by the beginning of Queen Victoria's reign they were both numerous and sophisticated. They provide a valuable source of information about fashion in all its aspects, but it would be idle to assume that they provide a picture of the appearance of any but the rich and influential, whose style of dressing was copied by those who could afford it. The social position occupied by the Duchesse de Berry, and later the Empress Eugenie, the Princesse Metternich, the Princess of Wales (later Queen Alexander), and to a lesser extent. Queen Victoria, ensured that they were copied in [31/32] all that they wore. In encouraging the jeweller Fauconnier to make jewels in the style of the Renaissance, the Duchesse de Berry started a fashion which lasted until the turn of the century and the large diamond bouquet, which was given to her at the time of the birth of the Due de Bordeaux in 1820, was reputed to have revived the interest in botanical jewellery*. In was likelv that this revival would have come about without any assistance from the Duchess, since the interest in naturalism stimulated by the artists of the Romantic movement was contemporaneous with an enthusiasm for scientific botany, plant collecting and plant development which amounted almost to a mania in this country in the first half of the nineteenth century. This preoccupation with natural form as a basis for design in decorative art was further stimulated by John Ruskin and William Morris through whose influence on the Art Nouveau style of the 1900s this line of botanical inspiration can be traced from the beginning of the century to the end.

The information provided by the fashion magazines can be supplemented by reference to the illustrated papers. Pictures of various state occasions and balls at court appeared regularly in The Illustrated London News, the first volumn of which appeared just in time to include an account of the 'Spitalfields' Ball, which was held on May 12th 1842 (see p. 43). Portraits and paintings of all kinds frequently contain jewellery, though there is a danger in using portraits for dating jewels or clothes which has already been pointed out by James Laver. The subjects are frequently not dressed in the most up-to-date fashions and old people in particular may be ten or fifteen years out of date. Royal (or Imperial) portraits are less susceptible to this particular hazard, and are worth studying for an idea of the jewellery required for a 'full dress' occasion in the nineteenth century. The portrait of Queen Adelaide by Sir William Beechey (plate 2) was painted c. 1835, the detail from Queen Victoria and her Family by Winterhalter, in 1846 (plate 5) and the Empress Eugenie, also by Winterhalter, in 1853 (plate 27).

Left: Plate 2. Adelaide, Queen Consort of William IV (1792-1849) by Sir William Beechey. c. 1831. Oil on canvas. The fashion for long chains, made from plaited or woven gold wire as well as linked chain dates from the early 'twenties. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery (NPG 1533). Right: Plate 5. Detail from a print after Winterhalter's Queen Victoria and her Family. Courtesy of the British Museum.

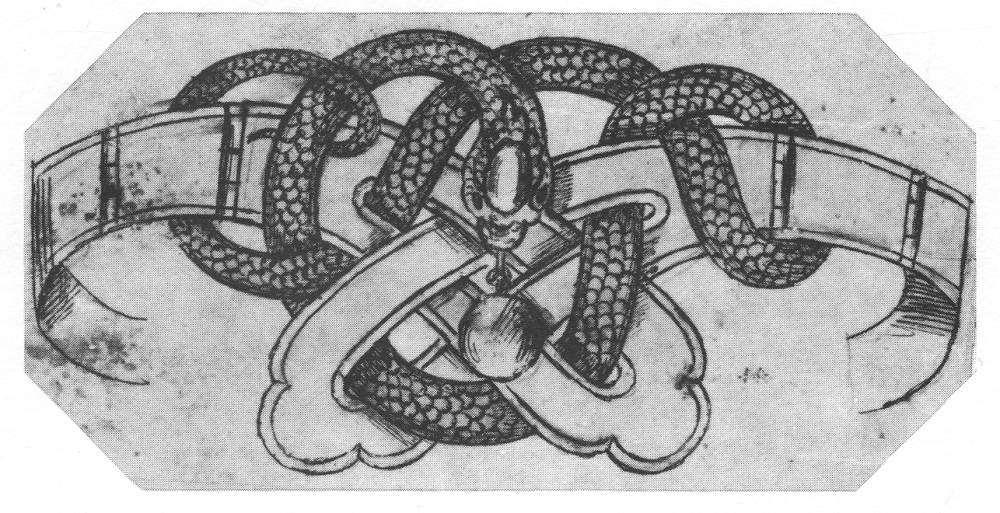

Between 1800 and 1830 the outlines of fashionable dress had altered completely, the waist had dropped to its natural level and below, the sleeves had increased in size, year by year, until they reached grotesque proportions, the influence of the Gothic style was now predominant, and by 1839 the World of Fashion was [32/34] commenting on the ubiquity of 'mediaeval' jewellery. The restoration of the monarchy in France had aroused interest in the sixteenth century, and the style Marie Stuart was universally adopted. Interest in this period was reinforced by the historical trend in Romantic literature, the presentation of Dumas' Henri III et sa Cour, Boieldieu's La Dame Blanche, and Victor Hugo's historical novels had the same effect on design in France that the works of Sir Walter Scott had in this country.

Plate 10. Design for a hinged gold bracelet, with an entwined serpent. American c. 1857. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York, Gift of Raphael Esmerian. The snake design as well as some faint and rather fragmentary bracelet designs behind are copies of French styles, fashionable in the mid-nineteenth century.

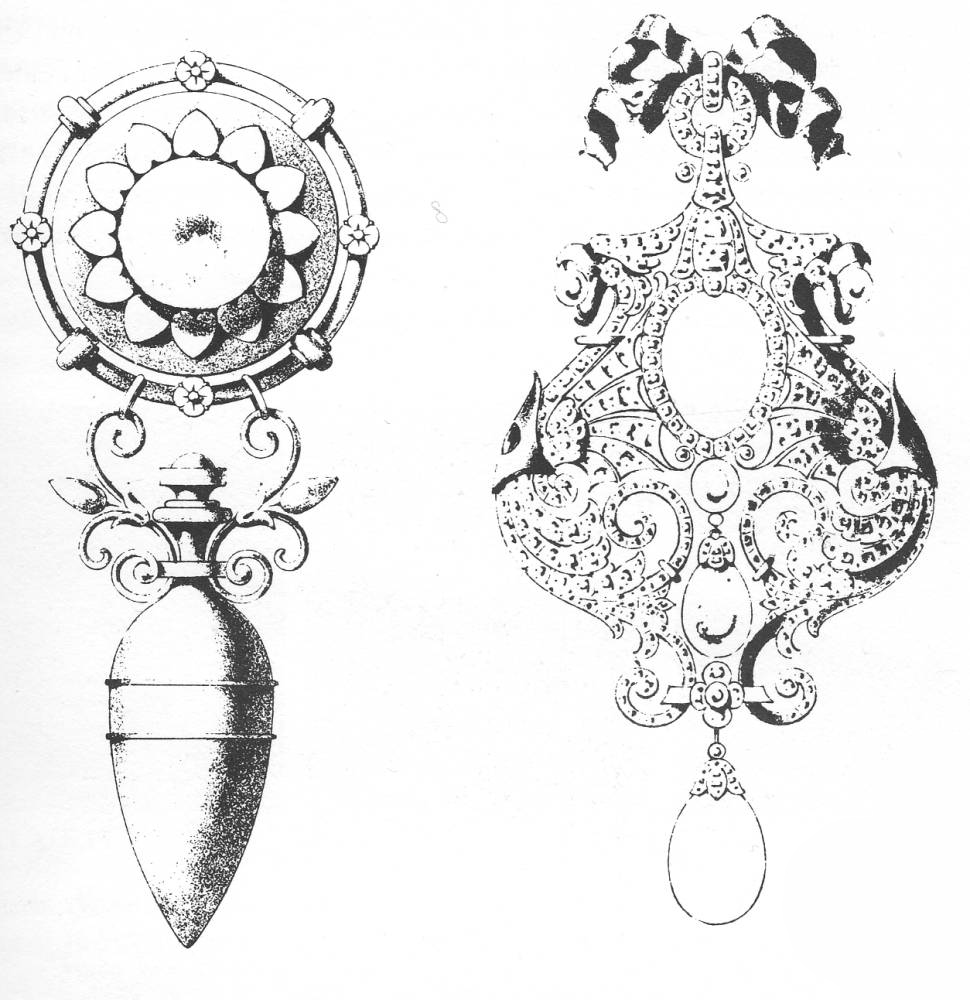

The first of these historical designs made no attempt to reproduce period details accurately but the passionate historical interest generated by the works of Hugo and Walter Scott led to a desire for correct copies of period costumes and jewellery, which were not only intended for costume balls but for daily wear as well. But historical accuracy appears to be irreconcilable with fashion in dress and at this point dress design turned away from close adherence to the late sixteenth-century style; conversely, the most successful interpretations of mediaeval and renaissance styles in jewellery are those that show the clearest understanding of the original models. This Romantic interest in antique jewellery produced two very [34/35] influential styles whose possibilities were explored throughout the Victorian period, the Gothic and the neo-Renaissance.

Plate 11. Engraved designs for pendants, American c. 1870. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum, New York, By this period ordinary commercial jewellery had few regional distinguishing features.

By the time Queen Victoria came to the throne in 1837 many of the trends which dominated jewellery design in the early years of her reign had been in circulation for some time. The neo-classic style of the mid-nineteenth century was evolved from the archeology-dominated Empire style of Napoleonic France and the Romantic style which had its beginnings at the time of the restoration of the Monarchy in France which still provided the inspiration for both dress and jewellery in the late thirties. The influence of the Romantic movement on jewellery design was felt [35/36] long after the characteristic large-sleeved and narrow-waisted silhouette had disappeared, to be replaced by the numerous padded petticoats which were to develop over the next twenty years into the vast crinolines of the sixties. Women were now more encumbered by clothes than they had been for half a century, and this change already seems to be reflected in the jewellery of the early years of Queen Victoria's reign, which became very massive and heavy by the middle of the century.

Plates 12a and 12b — Two charming diamond 'novelties' of the type fashionable at the end of the nineteenth century: Left: 'Honeymoon' brooch. Middle: Diamond Butterfly brooch . Right: Plate 12c. Diamond and pearl earrings the shape influenced by Indian jewellery. c. 1890. Indian jewellery, for many years advocated by the Aesthetes, became fashionable at the end of the century. Courtesy N. Bloom & Son.

In spite of this radical alteration in the proportions and character of the dresses, Gothic and Renaissance jewels which had aeen the perfect complement of Romantic costume retained their popularity; one example of this type of jewellery being the ferroniere, a pendant jewel worn suspended on the forehead in the manner of the blacksmith's wife in Leonardo da Vinci's portrait of La Belle Ferronière, first fashionable in 1829-1830, which enjoyed brief but widespread popularity in England between 1837 and 1843 during which time it was worn on every possible occasion.

The Romantic 'jewellery of the Middle Ages' of the thirties and thirties was largely based on jewellery of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries taken from the most accessible sources [36/37] available to the designers, i.e. Tudor and Jacobean portraits, and early engravings. The first man to introduce Gothic elements into lewellery, taking motifs from mediaeval sculpture and metalwork, was Francois Desirée Froment-Meurice whose early experiments in this style date from c.1840. The bracelet Gothique decorated with scenes from the life of St Louis which was shown in the Great Exhibition in 1851 was made by him in 1842. A silver brooch in this same style by Rudolphi, a Danish jeweller working in Paris who carried on the business started by the German, Wagner, to whom Froment-Meurice was apprenticed, was illustrated in the Journal of Design in 1849, but the first opportunity that the general public had to see this French Gothic jewellery came at the 1851 Exhibition when pieces by Froment Meurice and Rudolphi were shown. English mediaeval jewellery like that made by A.N.W. Pugin (Plate. 17) and the 'Gothic' brooches, 'mediaeval' and 'Holbein' jewels shown by other exhibitors in 1851, was very different from this sculptural French Gothic jewellery. The design of Pugin's jewellery, which was widely imitated, was based on motifs taken from ecclesiastical metalwork dating from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, of which he had a considerable collection. His detailed knowledge of the decoration of the Middle Ages gave his designs an authenticity which tended to elude most of his imitators, though there are some notable exceptions such as William Burges (Plate 19b) and Robert Phillips.

The French court during the Second Empire dazzled the rest of Europe with a display of jewellery of incredible ostentation. Some of the Crown jewels which had been dispersed at the time of the revolution were recovered and reset by Napoleon I and Charles X;

Napoleon III had a number of beautiful jewels made from the Diamants de le Couronne, which revived rococo and latc eighteenth century shapes. This diamond jewellery of the Second Empire probably represents the greatest refinement which middleclass taste is capable of producing, but it was the bijoux bourgeois of mid-nineteenth century France that set the fashions which are now regarded as typically Victorian.

This period also saw the beginning of the vogue for all kinds of curiosities in jewellery which was to persist until the turn of the century, sporting jeweller' (the bijoux hippiques beloved by Napoleon III, one of the few fashions which originated in England [37/38] and became even more popular in France, an unusual state of things noticeable at this time when tartan jewellery also became fashionable in France, probably attributable to the anglophilia of the Emperor); the jewelled insects of sinisterly realistic appearance which covered female headgear in the seventies; the imitation pointe de venise lace made of gold and diamonds, a technical tour de force achieved by French jewellers in the seventies; and many others. More ephemeral fashions included the jewels inspired by successful plays, the earrings in the shape of bells worn after the first production of Lex Cloches de Corneville, and the curious Benoiton chain, which was named after the nouveau riche family in Sardou's comedy La Famille Benoiton, (plates 9a & b), originally designed to hang from the bonnet, this idea was adapted to many different hair-ornaments. Patience, the comic opera by Gilbert and Sullivan, and The Colonel, by F.C. Burnand, which were both intended to ridicule the Aesthetes, had the effect, ironically enough, of making Aesthetic fashions widely popular.

Plates 9a & b. Fashionable hair ornaments from the 'Queen', 1867. This curious way of wearing chains or wreaths of flowers depending from the headress or the hair was introduced in 1865, and lasted to c. 1870. Collection of the author.

Reaction against the large and ostentatious jewellery of the sixties and seventies was bound to come as the artistic preferences of the Aesthetes gained wider acceptance. Even though the demand for lavish diamond jewellery never disappeared, indeed hardly diminished at all, the Arts and Crafts jewellery, Liberty's 'Celtic' designs and the modest English Art Nouveau which became fashionable at the end of the century enjoyed a quitc unexpected popularity. The taste for this small delicate jewellery spread and the minute pendants and lace pins of the nineties form the most complete contrast with the heavy brooches, bracelets and pendants of the preceding thirty years.

Never before in history had such startling technical and corrumercial changes taken place in the space of a hundred years as in the period from 1815 to 1914. Some of the engineering achievements which so profoundly affected the lives of the Victorian people even made an impression on jewellery design, and the foreign jewellery of all kinds which found its way to this country inevitably influenced English design, Indian and Japanese forms in particular being incorporated into late nineteenth century jewellery.

It is no longer fashionable to disparage the taste of the Victorians, all that is elegant and well-made (as well as much that [38/39] is appalling in both respects) is now appreciated and eagerly sought after, and it is interesting to see how much the jewellery of the twentieth century owes to the historical research and technical experiments undertaken by the jewellers of the nineteenth century.

25 February 2015