Left: Florence Claxton. Right: Adelaide Claxton. Both John and Charles Watkins. 1860s. Albumen silver print. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In the first chapter of the second volume of her English Female Artists (1876), Ellen C. Clayton includes a brief discussion of the sisters Florence and Adelaide Claxton. Clayton opens by pointing out that “it is one of the most disappointing paradoxes of modern times, that the very people who create the poetry, the humour, the ideal reflections of the heart or outer world, lead generally the most prosaic lives of all the community, even when in their own persons beautiful and graceful, or odd and eccentric” (41). Yet, even in her prosaic life, Florence Claxton, says Clayton, “had done what no female artist in all the world had attempted before—made a drawing on wood for a weekly illustrated paper” (44). In fact, she had an unconventional childhood and early life. Florence Claxton was born on 26 August 1838 in Florence, Italy, to the artist Marshall Claxton and his wife Sophia and baptized the following January in Greenwich, London. In 1850, when Florence was 12 years old, her father moved the family to Australia. Not achieving the success that he had hoped for in Sydney, Claxton moved his family again in 1854, to India, where they lived for three years, before returning to England, passing through Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Egypt on the way. This early experience of international travel, as Catherine Flood suggests, almost certainly gave the Claxton sisters “something of an outsider’s perspective on Victorian society” (Oxford DNB). Their arts education came primarily from their father, who for a time gave classes for ladies at his house in Kensington. In addition, both Florence and Adelaide attended classes at Cary’s (formerly Sass’s) Academy, one of the only art schools in London before 1860 to admit women.

In 1859, Florence signed the petition of the Society of Female Artists demanding that women be allowed to study at the Royal Academy Schools: the year before that, she exhibited a series of six satirical pen and ink drawings called Scenes from the Life of a Female Artist, at the Society of Female Artists Second Annual Exhibition, in 1858. An anonymous reviewer in The English Woman’s Journal that year praised Florence Claxton’s series and recommended them “to anyone who can appreciate fun”: “They are a fit commentary on the whole exhibition; there is the “ladies’ class.” the studio, the woodland wide-awake, all the aspirations, difficulties, disappointments, which lead in time to successes” (208).

That same year, Florence started working for the Illustrated Times, where, says Ellen Clayton, she was the first woman to draw her designs directly onto the woodblock. One such design is Claxton’s water-color The Choice of Paris: An Idyll (which also appeared as a full-page engraving in the Illustrated London News, 2 June 1860)—a work that undercuts the patriarchal authority of much celebrated art of the mid-nineteenth century in England. Both the painting and the engraving satirise the work of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, thus subverting the masculinist position of much fine art at mid-century. Jamie Horrocks, who has analysed this picture in detail, argues that it relies heavily on textual discourse, specifically that about primitivism, and it also shows how Pre-Raphaelite ideals were circulated in print as much as in painted images or illustrations (Horrocks 217). Claxton’s picture, says Horrocks, “compresses caricatures of more than fifteen Pre-Raphaelite paintings into a frenetic comic montage” (217). Horrocks calls this work “a study in parodic ekphrasis, an ersatz piece of Pre-Raphaelite art about Pre-Raphaelite art” (218). I would note that the picture is bisected by a wall, suggestive of the wall keeping women out of the PRB and out of the Royal Academy Schools until that very year. The commentary accompanying the picture in the The Illustrated London News notes the bisection “by a brick wall” in the engraving: “In the interior, the left-hand compartment, the principal group is that of Mr. Millais presenting the apple to a Pre-Raphaelite belle-ideal, whom he prefers to a figure of Raphael’s (from the well-known picture of The Marriage of the Virgin), and to a pretty, modern, English girl, dressed in the mode of the day, with plaited hair and crinoline complete” (The Illustrated London News 542). On the other side of the wall, various chivalric figures appear in the background, while in the foreground, the woman leaning against the wall is a parody of Calderon’s Broken Vows (1856), another lies on the ground, suggestive of Millais’ Apple Blossoms, while a third looks out the window above, thereby transgressing the boundary between interior and exterior scenes. As the The Illustrated London News points out, this woman is being dragged by her hair back into the room, a detail that emphasises the coercive nature of much patriarchally inspired art in the nineteenth century.

Florence Claxton. Left: The Choice of Paris: An Idyll. 1860. Watercolor. V & A Prints & Drawings Study Room. Right: The Choice of Paris—An Idyll. “in the Portland Gallery.” The Illustrated London News, June 2, 1860. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

March. Ye Spring Fashions. Florence Claxton. London Society, 1 (March 1862): 107.

Since both Florence and Adelaide had to make the most of their limited opportunities for paid work as artists, both became primarily illustrators rather than painters. By the early 1860s, they, along with another female illustrator, Mary Ellen Edwards (1838-1934), were contributing to London Society: An Illustrated Magazine of Light and Amusing Literature for the Hours of Relaxation. The editor, James Hogg, hired many accomplished illustrators, such as Walter Crane, and leading engravers like the Brothers Dalziel. The Claxton sisters’ work in London Society exemplifies the light-hearted entertaining tone of the magazine: for instance, here is Florence’s full-page engraving for March 1862: Ye Spring Fashions. At the top of the page (detail), a stylish young lady hands a scroll labeled “La Mode” to an obsequiously bowing dressmaker, while an eager-looking young woman brandishes aloft what looks like a bonnet or possibly helmet destined for Britannia—who waits at the bottom of the stairs, as the young woman knocks over irritated looking ladies holding hat boxes and dress patterns. At the bottom of the scene stands Britannia on the seashore, with some other women, children, and a man in a straw boater, all awaiting the arrival of the spring fashions, evidently coming from France over the Channel to England, the cash box an emblem of the cash nexus. Here again is another set of frames: what look like wooden branches framing the whole scene and a curtain open to reveal the top half of the picture. Britannia herself is framed by the crinoline she is wearing, waiting for the skirt that will cover it. These frames evoke a sense of confinement, of course, as well as of artifice and mimetic distance. In this way, Claxton subtly critiques the restrictive nature of cultural norms for women in the early 1860s even as she seems to mock women themselves for succumbing to the ideological imperative of being empty-headed slaves to fashion. She makes mid-Victorian consumerism appear ridiculous and yet an impelling force, since in this image the women rush or are pushed down the stairs towards the shore and the waiting buyers of the latest trends in ladies’ millinery.

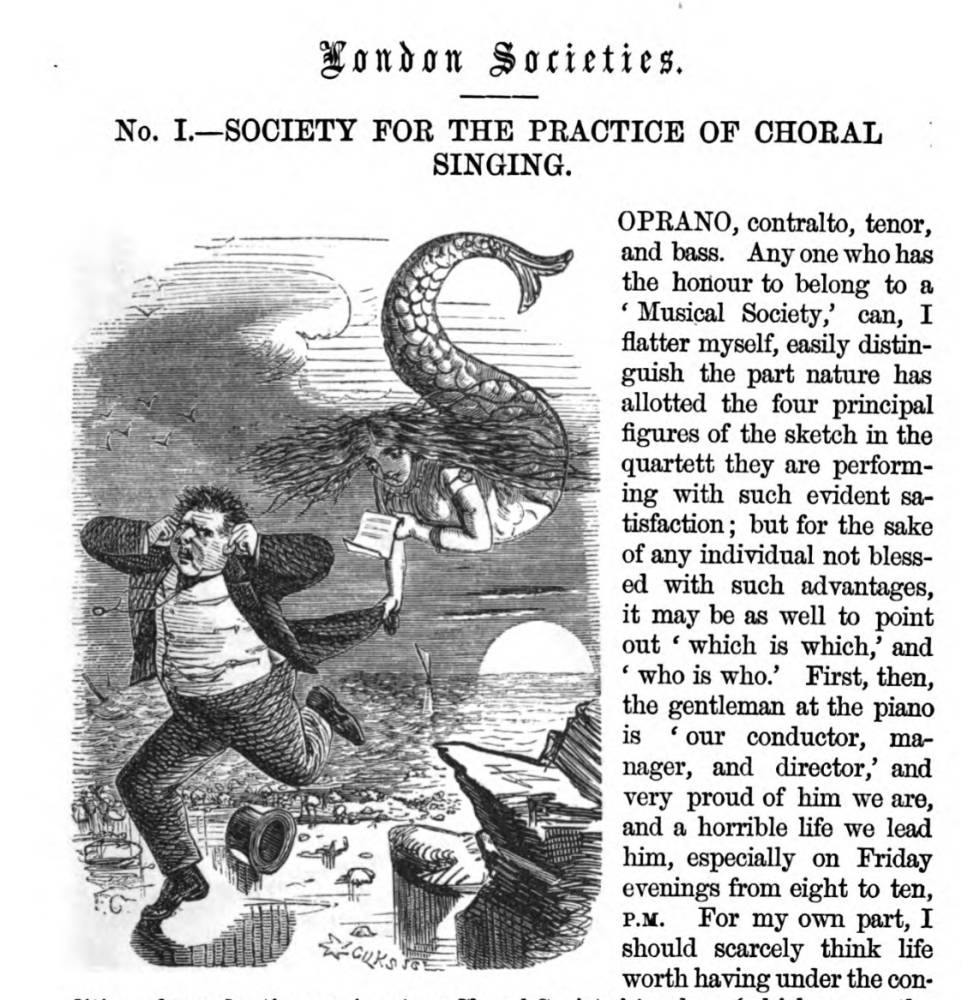

“London Societies. No. I. Society for the Practice of Part-Singing.” London Society 1 (April 1862): 209.

Florence’s Society for the Practice of Part-Singing (April 1862) is an illustration for a piece told by one of the “Bassi,” the man with his mouth wide open standing next to the pianist.

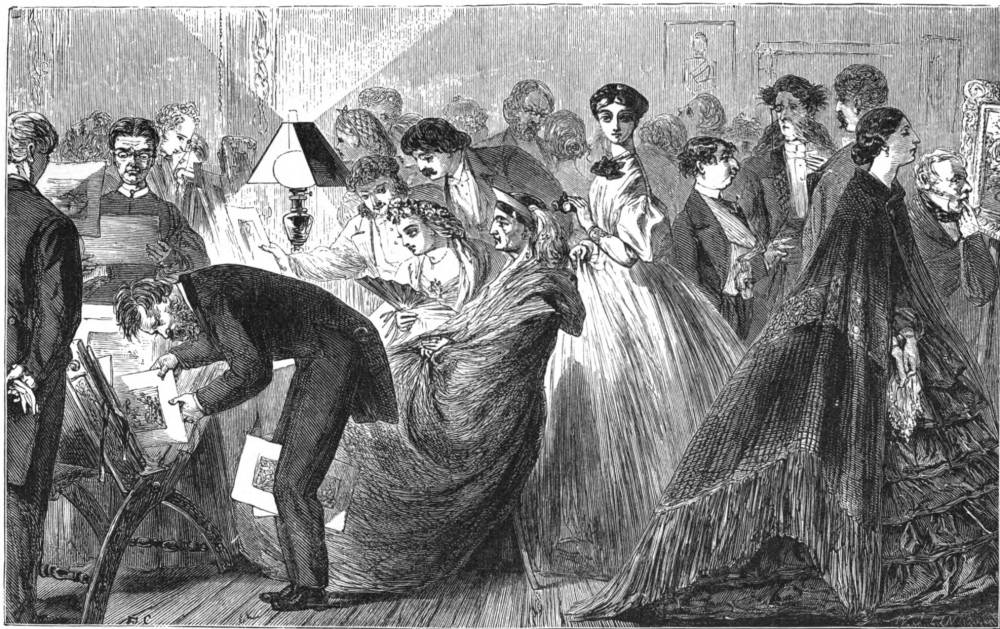

The essay gently pokes fun at the “fine women” in this choral society—much more gently than Claxton treats them with her mermaid initial at the start of the essay (209). Similarly, her illustration for the “Conversazione at Willis’s Rooms: The Artists and Amateurs’ Society” (May 1862) accompanies a text that is archly satirical of the gauche, provincial devotees of this pastime and describes the figures in the engraving thus:

That little artist stooping over the portfolio stand. . . what is there to be said of him, save that his hair, his coat, his boots, his general tournure, cry aloud, ‘a person not in society?’ That strong-minded looking lady next him is undeniably a member of the same profession; but I object to her myself as conventional. Why should people refuse to recognize the ‘female artist’ unless so cruelly caricatured? She is introduced, no doubt, as a foil to that pretty creature in the centre holding the opera glass; she who has ventured under the wing of her mamma and elder sister so far into Vanity Fair. (379)

It is significant that Claxton’s engraving is harsher in its treatment of the scene than the commentary.

A Conversazione at Willis’s Rooms: ‘The Artists’ and Amateurs’ Society.’ London Society. 1 (April 1862): 378. Details: Man inspecting prints. Heads of people at right.

Arguably, Florence’s illustrations are frequently sharper and more grotesque than Adelaide’s, which tend to appeal to emotions such as pity or compassion.

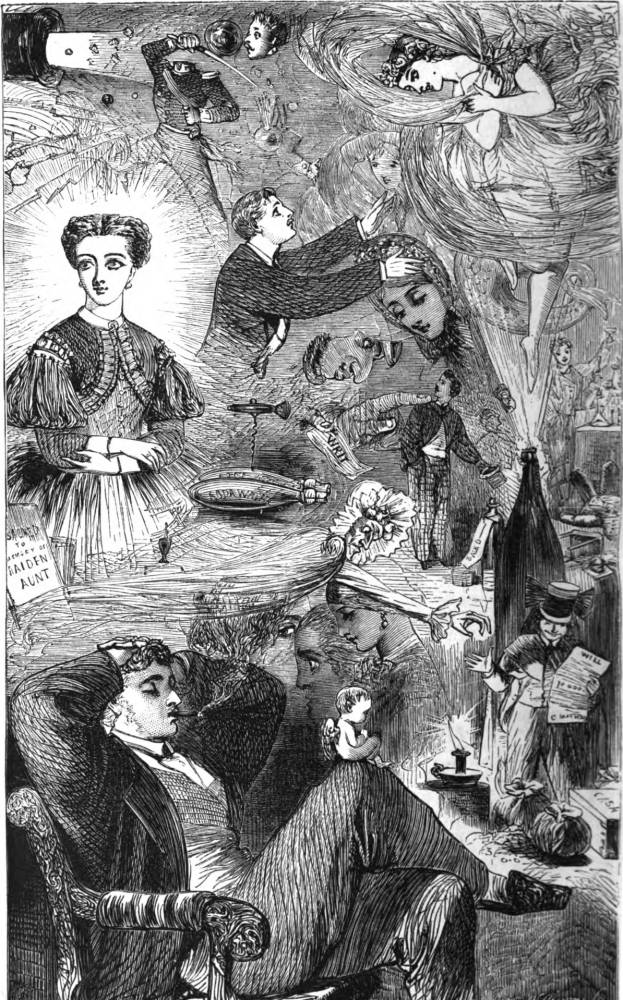

Left: The Daily Governess. Adelaide Claxton. Middle: The Young Lady’s New Year’s Dream Adelaide Claxton. Right: The Young Gentleman’s New Year’s Dream. Florence Claxton.

In the June 1862 issue of London Society, Adelaide contributed an engraving called The Daily Governess to accompany a poem that describes the “sordid cares” and sad, isolating humiliations that were the lot of most governesses. For the Christmas Extra Number of London Society that year, both Claxton sisters contributed illustrations: The Young Gentleman’s New Year’s Dream, by Florence, and The Young Lady’s New Year’s Dream by Adelaide. Whereas Florence’s engraving includes details such as the champagne cork (or cannonball?) blowing off the young gentleman’s head in the upper left corner of the scene and the witch-like maiden aunt (whose tombstone appears at the left) reaching across to drop money into the hand of the profligate young man at the right hand side of the picture, Adelaide’s drawing features mainly handsome young men lining up to dance with and eventually—one of them anyway—to marry the dreaming young lady.

The Dance Pastoral—The Hop Pic-Nicial. Florence Claxton. 14 (August 1868): 144.

In 1868, Florence produced eight large cuts for “The Physiology of the Dance: A Set arranged in Eight Figures by Tom Hood” for London Society. These illustrations demonstrate both Claxton’s technical achievement and her slyly ironic eye for the ridiculous.

That same year, Florence married Ernest Farrington, a French photographer and engineer, after which she ceased most of her artistic work, although she did write and illustrate a comic picture book, The Adventures of a Woman in Search of Her Rights (1870). Little is known of Florence Claxton’s later life. She died as a result of suicide in 1920, but she has left us with many delightful satirical illustrations that remain sharply witty and surprisingly apposite today. Adelaide married George Gordon Turner in 1874, had a son when she was 43, and continued illustrating for magazines such as Judy. She died at age 86 in 1927.

Bibliography

Anonymous. “XXVIII.--The Society of Female Artists.” The Englishwoman's Journal. 1.3 (1858): 205-08.

Claxton, Florence. The Adventures of a Woman in Search of Her Rights. London: Graphotyping Company, 1870.

_____. “The Choice of Paris: An Idyll.” Illustrated London News (2 June 1860): 541.

Clayton, Ellen C. English Female Artists. 2 vols. Vol. 2. London: Tinsley Brothers, 1876.

Cooke, Simon. Illustrated Periodicals of the 1860s. London: The British Library; Newcastle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2010.

Flood, Catherine. “Claxton [married name Farrington], Florence Ann (1838-1920),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Web. 3 June 2020.

Flood, Catherine.. “Contrary to the Habits of Their Sex? Women Drawing on Wood and the Careers of Florence and Adelaide Claxton,” Crafting the Woman Professional in the Long Nineteenth Century. Ed. Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi and Patricia Zakreski. London: Routledge, 2016.

Gaze, Delia, ed. Dictionary of Women Artists, Vol. 1. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

Fredeman, William E. “Pre-Raphaelites in Caricature: 'The Choice of Paris: An Idyll' by Florence Claxton.” The Burlington Magazine, 102, no. 69 (1960): 523–29. JSTOR. Web. 3 June 2020.

Horrocks, Jamie. “Pre-Raphaelite Primitivism and the Periodical Press: Florence Claxton’s “The Choice of Paris,” Visual Culture in Britain, 18:2 (2017): 217-46, DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2017.1328286.

Jobling, Paul, and David Crowley. Graphic Design: Reproduction and Representation Since 1800. Manchester University Press, 1996.

Van Remoortel, Marianne. Women, Work and the Victorian Periodical: Living by the Press. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Westendorf, Karen. “Florence Ann (1838-1920) and Adelaide Sophia Claxton (1841-1927),” Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum & Galleries. Web. 3 June 2020.

Last modified 3 June 2020