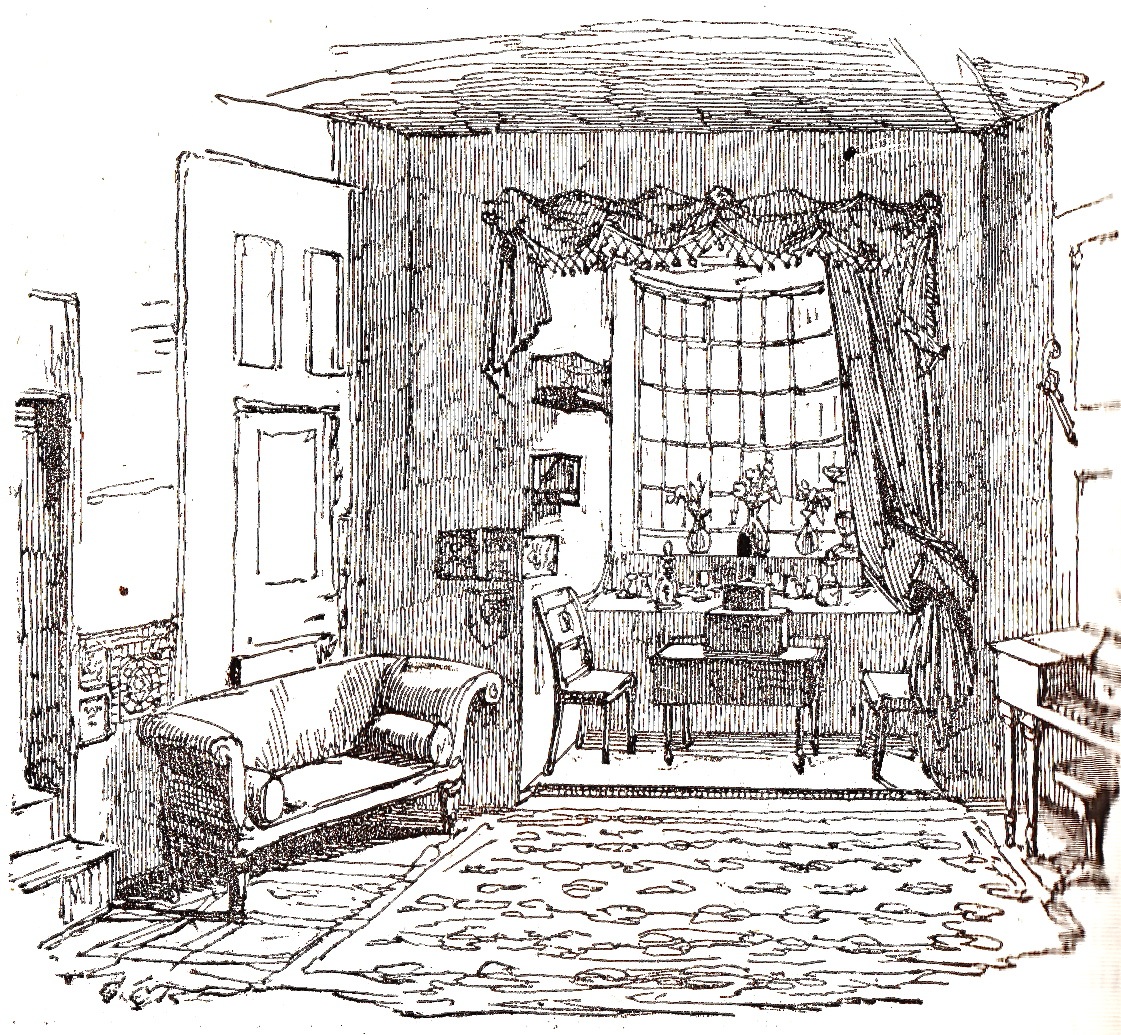

Chamber in the Salt Tower. — George Cruikshank. Seventh instalment, July 1840 number. Fiftieth illustration and twenty-eighth wood-engraving in William Harrison Ainsworth's The Tower of London. A Historical Romance. Illustration for Book the Second, Chapter XVI. 8.7 cm high x 9.3 wide, vignetted, at the bottom of p. 222: running head, "The Salt Tower." The tranquil scene of a tastefully furnished Victorian parlour with elegant drapery belies the gloomy past of the Salt Tower as a place of brutal interrogation of state prisoners. Curiously, the present occupant has blocked the entrances to both secret passages with a love-seat (left) and a small piano (right). The astrological sign dated "30 May 1561" by would-be sorceror Hew Draper, a Bristol innkeeper arrested for dabbling in the black arts, is just to the right of the fireplace, mute testimony to the Salt Tower's unsavoury past.

Click on the image to enlarge it. Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Relevant Passage

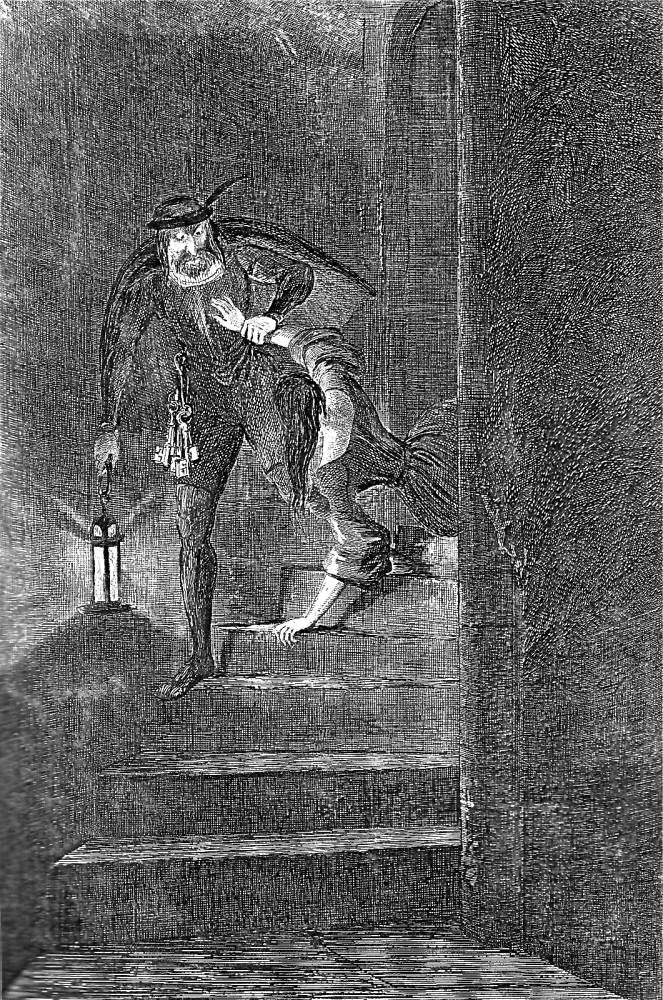

Quitting this chamber, Nightgall ascended a winding stone staircase which brought him to an arched door, leading to the room just described. Taking a key from the bunch at his girdle, he unlocked it, and entered the room. A female was seated in one corner with her face buried in her hands. Raising her head at his approach, she disclosed the features of Cicely. Her eyes were red with weeping — and her figure attenuated by long suffering. Conceiving from the savage expression of the jailor's countenance that he meditated some further act of cruelty, she uttered a loud shriek, and tried to avoid him. [Chapter XVI. — "What befel Cicely in the Salt Tower," p. 223]

Illustrations of the Salt Tower in Chapter XVI

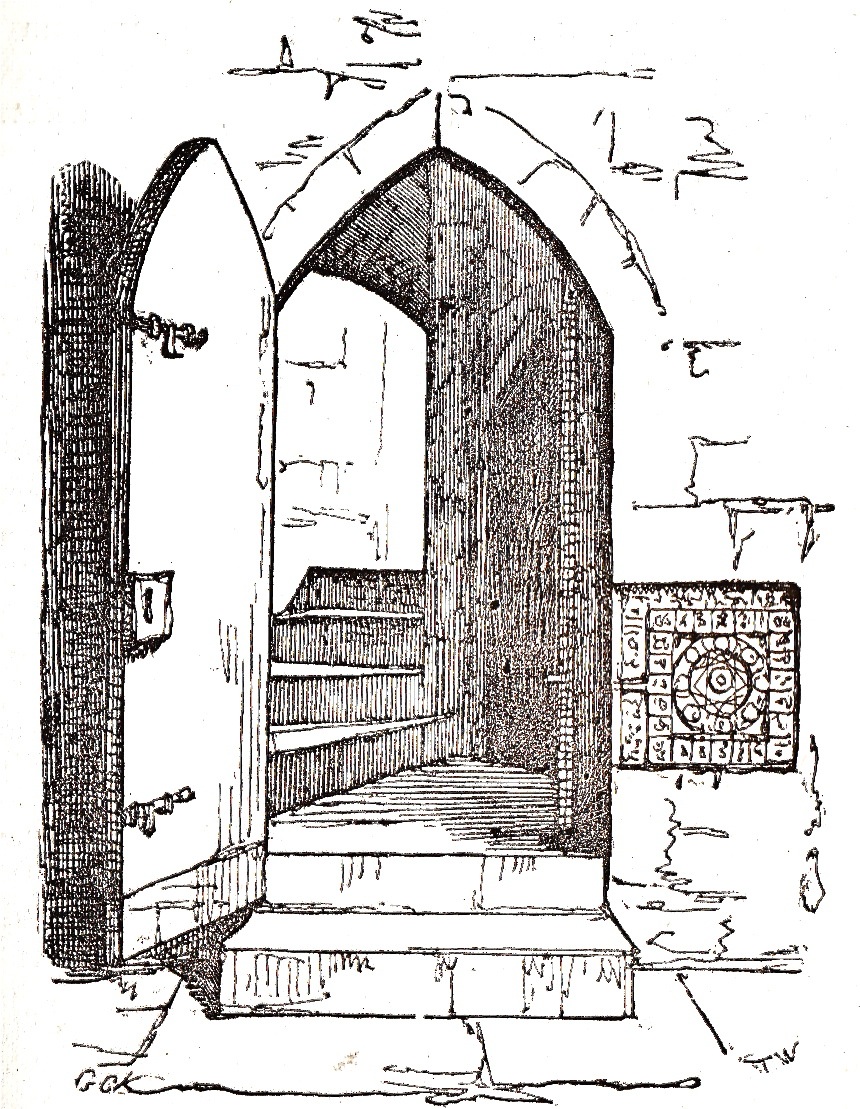

Left: The wood-engraving of the mysterious staircase as it looked in 1840, Secret Staircase in the Salt Tower (July 1840). Centre: Arched Door in the Salt Tower Communicating with Secret Staircase (July 1840). Right: The brutal jailor callously trying to shift his victim's location in order to avoid detection, Lawrence Nightgall Dragging Cicely Down the secret stairs in the Salt Tower (July 1840). [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Although this particular wood-engraving does nothing to enhance the atmosphere of Gothic romance, in this chapter Ainsworth drops the political-historical plot surrounding Mary Tudor, Courtenay, and the Princess Elizabeth in favour of the strain of the kind of fiction pioneered by Matthew G. Lewis and Anne Radcliffe. Nightgall recaptures Cholmondeley, and then proceeds to deal with the problem of Cicely. The sadistic jailor, implies Ainsworth, buries Alexia alive in the basement of the Devlin Tower, then goes to visit her imprisoned daughter in the Salt Tower, where most of the chapter's action occurs. Fearing that the young esquire may have detected where she has been held a prisoner, Nightgall attempts to transfer her to a cell in the basement of another tower. Her screaming and refusal to leave her place of confinement voluntarily prompt Nightgall to drag her down a secret staircase to a dark chamber beneath the Tower leading to the Iron Gate.This staircase appears a number of times in the illustrations for this chapter, although Cruikshank contrasts the cheerfully furnished chamber of 1840 with plainer views which suggest how the staircase, doorway, and chamber would have looked three hundred years earlier.

Seventeen years after Ainsworth published the novel, architect Anthony Salvin restored the Salt Tower's exterior and windows; perhaps the attention he devoted to it was the direct result of the importance of the Salt Tower in the novel. The Salt Tower appears first in North View of the Salt Tower, and again in Masque in the Palace Garden of the Tower, Secret Staircase in the Salt Tower, and Arched Door in the Salt Tower Communicating with Secret Staircase, Basement Chamber in the Salt Tower, as well as torture scenes probably enacted in the dungeons of the Salt Tower, significantly Elizabeth confronted with Wyat in the Torture-Chamber in Chapter 34 in the final instalment. Ainsworth's firing the public imagination probably led to the government's commissioning Salvin, at the behest of Prince Albert, to undertake a comprehensive restoration of the Tower's mediaeval and Tudor buildings.

Bibliography

"Ainsworth, William Harrison." http://biography.com

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Tower of London. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Richard Bentley, 1840.

Burton, Anthony. "Cruikshank as an Illustrator of Fiction." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 92-128.

Carver, Stephen. Ainsworth and Friends: Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic. 11 September 2017.

Department of Environment, Great Britain. The Tower of London. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1967, rpt. 1971.

Chesson, Wilfred Hugh. George Cruikshank. The Popular Library of Art. London: Duckworth, 1908.

Golden, Catherine J. "Ainsworth, William Harrison (1805-1882." Victorian Britain: An Encyclopedia, ed. Sally Mitchell. New York and London: Garland, 1988. Page 14.

Kelly, Patrick. "William Harrison Ainsworth." Dictionary of Literary Biography, Vol. 21, "Victorian Novelists Before 1885," ed. Ira Bruce Nadel and William E. Fredeman. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. Pp. 3-9.

McLean, Ruari. George Cruikshank: His Life and Work as a Book Illustrator. English Masters of Black-and-White. London: Art and Technics, 1948.

Pitkin Pictorials. Prisoners in the Tower. Caterham & Crawley: Garrod and Lofthouse International, 1972.

Sutherland, John. "The Tower of London" in The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 19893. P. 633.

Steig, Michael. "George Cruikshank and the Grotesque: A Psychodynamic Approach." George Cruikshank: A Revaluation. Ed. Robert L. Patten. Princeton: Princeton U. P., 1974, rev., 1992. Pp. 189-212.

Vogler, Richard A. Graphic Works of George Cruikshank. Dover Pictorial Archive Series. New York: Dover, 1979.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Vann, J. Don. "The Tower of London, thirteen parts in twelve monthly instalments, January-December 1840." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: MLA, 1985. Pp. 19-20.

Last modified 17 October 2017