[Formatted, with the addition of headings, images and captions, by JB. All images other than the first one are either from our own website, or from the Library of Congress Digital Gallery. Details of the latter are given at the end. They can be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, provided you cite the photographer/source, and link your document to the Victorian Web or cite it in a print one. Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

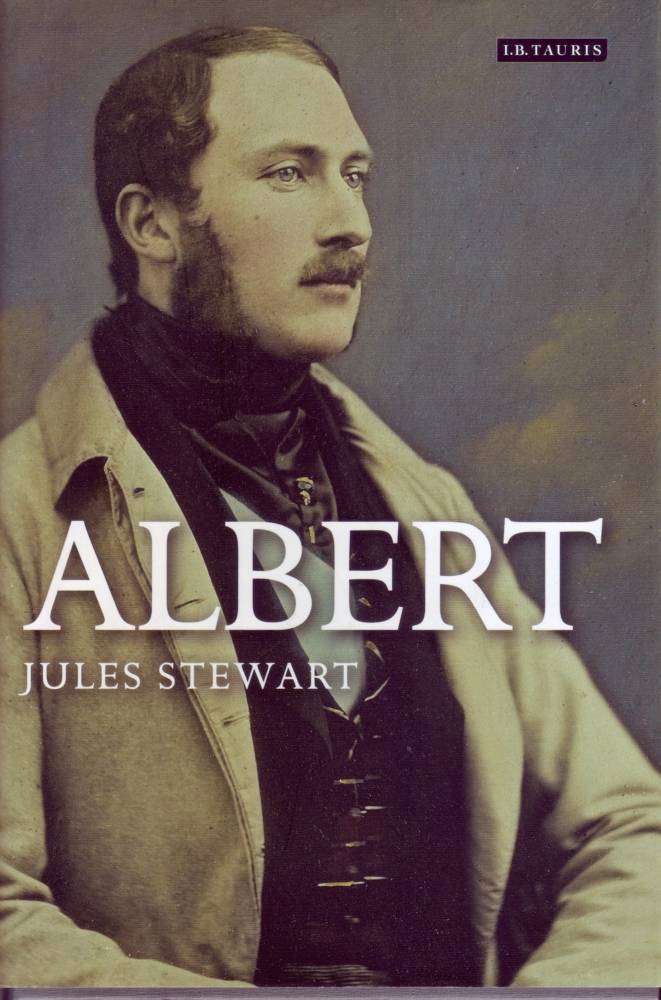

Front cover of the book under review

During Queen Victoria's prolonged period of mourning, her determination to commemorate her husband gave Prince Albert more of a presence in the public imagination than he had ever had before. Prime examples of monuments to him are, of course, the Albert Memorial and Royal Albert Hall in South Kensington, near Victoria's own birthplace, Kensington Palace, and the site of his own brainchild, the Great Exhibition. There were written memorials as well. The Queen herself commissioned the Scottish lawyer and writer, Theodore Martin, to write his biography, and a weighty five-volume tome eventually appeared in 1882 as The Life of HRH the Prince Consort. Several other biographies followed, with Jules Stewart writing this, the latest, to mark the 150th year of the Prince's death. Stewart has made use of all the previous ones, especially Martin's exhaustive account, duly acknowledging his debts to them in his endnotes and bibliography. The result is a compact, informative book for the wider market, written in an accessible style, and containing over twenty illustrations including a useful family tree and a reproduction of the Prince's coat of arms.

Earlier Life

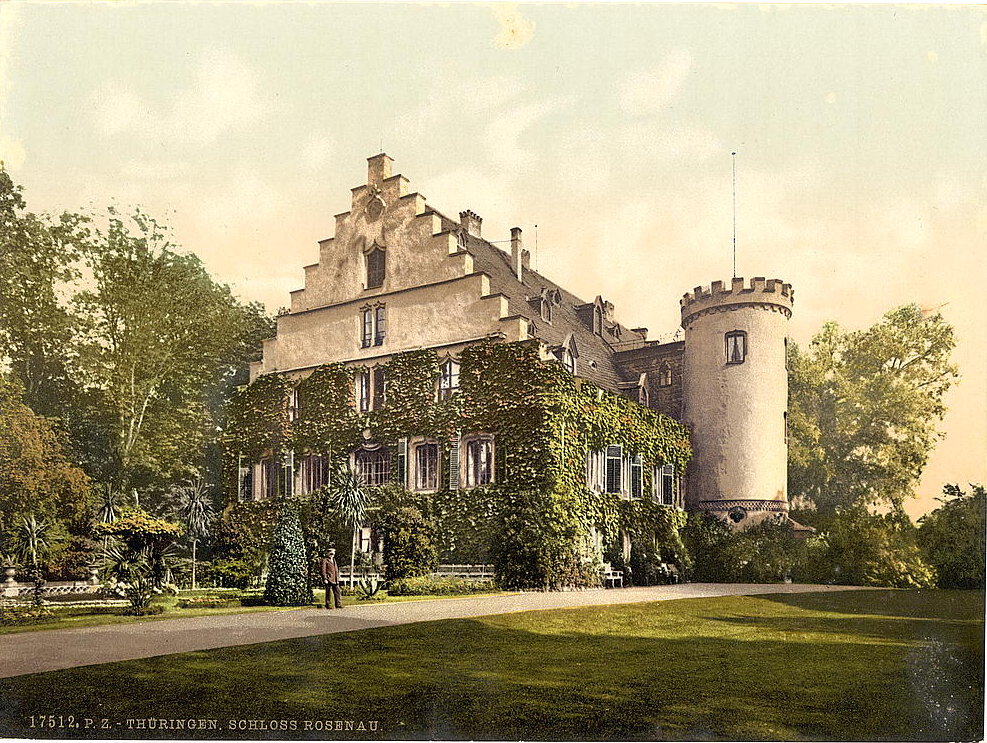

Left: "[P]astoral Coburg" in Bavaria (Stewart 3), Albert's native town. Right: Rosenau, the summer home where Prince Albert was born and brought up — a fifteenth-century castle close to Coburg. Both images come from the Library of Congress Digital Gallery.

In a straightforward chronological account of Prince Albert's life, Stewart explains that he was the younger son of Duke Ernest of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld and his wife Princess Louise of Saxe-Coburg-Altenburg. The couple were both promiscuous (Stewart later talks of Albert's "philandering biological father," 146), and soon went their separate ways. After their divorce, their two sons, Ernest and Albert, grew up in the Duke's summer home of Rosenau, four miles from Coburg, under the guidance of a young philosophy graduate, Johan Florschutz, selected for the purpose by the Duke's physician and adviser Baron Christian Friedrich Stockmar. From Florschutz the boys received a classical education; but their tutor also taught them modern languages, mathematics and so on, and took them on a Grand European tour, familiarising them with the great continental capitals and taking them to museums and concerts. Then came the search for suitable spouses. Ernest was to inherit his father's dukedom, but Stockmar wanted to bring about a union between the House of Saxe-Coburg and the British royal family, as did the young man's uncle, King Leopold of the Belgians — widower of the late Princess Charlotte of England, and brother of the Duchess of Kent (born Victoria Saxe-Coburg Saalfield). He was therefore uncle to the Duchess's daughter Victoria as well as to Albert. The opportunity came when the Duchess invited these two nephews to Victoria's seventeenth birthday. Victoria, now heir presumptive to the English throne, had several suitors, including William and Alexander of Orange and the Duke of Brunswick. The cheap press even gossiped that the 54-year-old U. S. President Martin Van Buren had "thrown his hat into the ring" (23). But, as Leopold had hoped, Victoria was smitten by Albert, confessing to her uncle Leopold that she “cried bitterly, very bitterly” (25) when he left. She was still very young, however, and decided to wait.

Marriage

After leaving London, Albert went to Belgium and then to Bonn where he enrolled at Bonn University. On Victoria's accession in 1837, he sent his felicitations, but tactfully kept out of the picture, realizing that this would be a period of adjustment. He took a long tour of the Italian cities, visiting Rome, Florence, Milan and Genoa, and returned to Windsor only in October 1839. Victoria welcomed him with open arms, and they were married at the Chapel Royal of St James's Palace on 10 February 1840. However, the match was not a popular one. Albert was, after all, a foreigner. Parliament refused the usual allowance of £50,000 to the sovereign's spouse, reducing it to £30,000. Moreover, it overruled Victoria's wish for him to be given the title of Prince Consort — it would be granted belatedly, along with other royal privileges, in 1857, only four years before his death. He did have certain rights: the Regency Bill of 1840 entitled him to rule in the event of the Queen's death so long as their children were under 18 years of age. Besides, he was allowed to occupy the seat next to the throne at official functions, was made a member of the Privy Council, and appointed the Colonel Commandant of the 11th Hussars. But the public in general remained prejudiced against him, and Stewart reminds us that, in all, seven assassination attempts were to be made against the royal couple.

In these circumstances, despite the respect he earned from some of the most powerful men of the day, and his deep interest in European affairs, it was impossible for Albert to make his mark on the political scene. As a historian, Stewart cannot resist giving and elaborating on the political views expressed in Albert's personal letters to friends and politicians, but admits that "[h]is largely self-imposed, it must be said, political vocation in the affairs of a foreign land never sat comfortably with him" (78), and that neither he (nor the Queen herself for that matter) could have much practical effect on the running of the country and its policies. Nevertheless, at home Albert was king: Stewart repeats without commenting on its authenticity the oft-told story that once, when Albert had locked the door of his room, he refused to allow Victoria to enter until she pleaded with him, not as his Queen, but as his wife.

Cultural, Social and Building Projects

More importantly, he actively sought outlets for his untapped energies, and Stewart delineates in rich detail the enormous amount of good that he subsequently did for the social, cultural and artistic life of his adopted land. His first chance came when Prime Minister Robert Peel made him the chairman of the royal commission formed to advise the government on rebuilding the Houses of Parliament. Albert appointed a select fine arts committee which recommended that the House of Lords be decorated with large frescos. Artists and sculptors were recruited, their decorative works adding grandeur to the buildings and bringing "multitudes" to admire them, fulfilling his “ambition of raising public tastes in art” (70). Next, Albert tried to improve the musical taste of his people. He himself was an able composer: Stewart tells us that he was responsible for “nearly forty chorales, anthems and church hymns and other works” (73). He reorganised the Queen's musicians, then playing only wind instruments, into a string ensemble, raising their level and arranging concerts for both private and public entertainment. The couple celebrated their first Christmas together with the masterworks of great composers like Schubert, Beethoven, Mozart and Haydn. Two years later, Albert invited his favourite composer Mendelssohn to play at Buckingham Palace.

Next, he turned to the plight of the poor. A man of high moral conscience, derived, Stewart surmises later, "in part from his deep-rooted Lutheran faith" (99), Albert was shocked at the level of poverty in England in the 1840s. This was a time when manufacturing and trade had slumped, and the country as a whole was in economic crisis. On rides outside Buckingham Palace, he had seen with his own eyes the misery of the poor, and been “dismayed by what he saw and heard — this, after all, was the metropolis, the epicentre of the world's greatest empire” (49). As president of the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labour Classes, he encouraged the building of new houses for working people with proper ventilation and sanitation. Its first urban project was a development in Pentonville, North London, in 1846. The Prince urged rich philanthropists to give generously to similar projects. The Model Lodge in Kennington was built to create similar dry, fire-resistant, affordable houses. He also tried to improve the welfare pension scheme for servants who had hitherto had no such provision. In these and other ways, Albert "established his credentials as a royal champion of the poor” (95). Stewart notes that the Prince wanted four provisions made for them: education for their children, along with industrial training; good dwellings; the granting of allotments; and savings banks and benevolent societies. He quotes Albert as saying: "I shall never cease to promote these four objects wherever and whenever I can" (98).

Closer to home, Albert, who had grown up in the bracing rustic atmosphere of Rosenau, was keen to build palaces for the royal family where he could get away from the “smoke-choked atmosphere of London” (73). In 1844, Peel told him that his friend Lady Blatchfield might offer him her estate, Osborne House, on the Isle of Wight. Albert first took it on a year's lease, and then bought it, asking the eminent builder/architect Thomas Cubitt to re-design and enlarge it. It became, and remained, Queen Victoria's second home; she died there in 1901. Similarly, they wanted a home in Scotland. They acquired Balmoral Castle there in 1852. Stewart speculates that this “retreat was like that of small Germanic kingdoms of old fairy-stories, in which a king and queen, their sovereignty always recognized, are nonetheless on a carpet-slipper basis with their subjects” (81). The historian Michael Lynch makes the more significant point that “the Scottishness of Balmoral helped to give the monarchy a truly British dimension for the first time” (146).

Chancellorship of the University of Cambridge

Albert's ideas about education were by no means confined to the working-classes. When the Chancellorship of Cambridge University fell vacant in 1847, William Whewell, the Master of Trinity College, urged the Prince to allow his name to be put up for election. The Prince was delighted but insisted that he would accept the position only if elected unopposed. In the event, the dissenting members of the university put up the candidacy of the Earl of Powis, a Tory and a Fellow of St John's College, an arch rival of Trinity. The result was a close call, 953 for Albert to 837 for Powis. Nevertheless, the Prince accepted the position and thus became the first foreigner to hold the Chancellorship. On assuming it, he set about modernising the University's antiquated teaching system and syllabus: despite stiff opposition from the older members of the University, new subjects and courses, especially in the sciences, were introduced, and a “reformed, modernised scheme of studies” was “put into effect in the Michaelmas term of 1850” (88). Again, this is no less than the truth. As the Conservative politician and historian Robert Rhodes James has said, Albert brought about a “spectacular revival of Cambridge University from medieval slumber to a world eminence it has never surrendered” (xii).

The Great Exhibition and "Albertopolis"

Left to right: (a) Detail of the Albert Memorial, showing a seated Prince Albert holding the catalogue of the Great Exhibition, and facing the Royal Albert Hall. (b) The figure of Prince Albert, by the sculptor Alfred Drury, presides over the main entrance to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. (c) Drury's Albert in its setting.

But Albert, with his European background, made his greatest contribution by initiating and organizing the Great Exhibition of 1851. He had heard of the success of the Exposition Nationale in Paris, and decided to emulate this in London on a grander scale by inviting foreign participants. Stewart says in the introduction that his aim is "to relate the life and works of a man about whom too little is known and appreciated by the present generation" (5), and he retells this part of the story with particular gusto. In 1850, Albert set up and presided over a Royal Commission to work out the details, and appointed Henry Cole, the Assistant Keeper of the Public Records, as its chief organizer. The Commission made elaborate plans and sketches. The public, individually and collectively, raised funds for the Exhibition. First, the venue had to be agreed upon. When Hyde Park was suggested, several members of the Parliament objected but they were soon brought into line. Next, it was decided to enrol almost fourteen thousand exhibitors, a large number of whom were foreigners. When the Exhibition opened, there were more than a hundred thousand exhibits. The general public responded with great enthusiasm, and about twenty-five thousand people passed through its gates on the day of its inauguration. The price of the entrance fee was reduced for the working-class people who thronged to the Exhibition in large numbers. Londoners, mostly mildly xenophobic, were exposed to the sight of many foreigners in their midst. The Times reported that “[s]trange-looking foreigners passed along in the stream . . . Every variety of beard, moustache, coat and trousers was permitted for the day” (134). Nevertheless, the Exhibition was a resounding success. Over six million people, including literary luminaries like Dickens, Flaubert and Charlotte Brontë, visited it. When it was over after five months, the structure was moved to Sydenham, South London, in 1854. Unfortunately, only the Italian terraces in front of it remain now because it burned down in 1936. But the idea of an international exhibition caught on, and has persisted: World Fairs remain a feature of world culture.

Stewart reminds us of how one success led to another. The exhibition proved to be a commercial triumph too, generating a revenue of over £500,00. The Prince decided to use the surplus to build museums of arts and sciences in London. Again, Stewart traces the familiar stages by which the Royal Commission acquired the nearby derelict land in what eventually became the fashionable area of South Kensington, built the South Kensington Museum which later developed into the now famous Victoria and Albert Museum, and went on to erect the Natural History Museum, the Royal College of Music, and the Royal College of Art, among others. "Albertopolis," as it became known, had arrived.

Army Reform

Left: The Prince Consort's Library, Aldershot. Right: Prince Albert's coat of arms on the façade. of the library, with his motto, "Treu und Fest" ("True and Steadfast").

.Albert's triumph on this occasion, however, was short-lived. England was now involved in the events leading up to the Crimean War. The Prince felt that England's interference between Russia and Turkey would weaken Europe's position, but the British at heart remained pro-Turkish, denouncing the Prince as a foreign sympathiser: the newspapers "launched a concerted attack on Albert, the nation's erstwhile man of the hour, accusing him of a raft of offences, from meddling in foreign affairs to conspiring with foreign governments" (149). Having burnt his fingers in the political scene, he turned to military matters. In 1953, he was appointed a Colonel in the Grenadier Guards. He set out to re-organize the army and made suggestions for its improvement. In particular, he wanted it to have a permanent base. For this purpose, he persuaded the government to purchase 3000-acre tract in Aldershot which became, and remains, Britain's garrison town. He built the military library there at his own expense.

"Albert the Good"?

Stewart, who mentions "Albert's inherent morose character" in passing (151), admits that he was "not perfection personified: he could easily sink into ill-temper and gloom, he took a severe hand to his children's upbringing, and he was highly sensitive to criticism." Yet he feels that such "shortcomings hardly invalidate his kindness, wisdom and high moral principles" (212). There is little sense here of the conflict between the two sides of him — of the driven, conflicted man, the apparently "inexplicable enigma" (182), described by Lytton Strachey in his iconoclastic Queen Victoria of 1922. As for his marriage, Stewart almost eschews discussing the private life of the royals, perhaps (again) in order to avoid speculation. He occasionally hints at tiffs and quarrels between the couple. For instance, he tells us towards the end that on their twenty-first wedding anniversary, Albert wrote to his old mentor Stockmar, “'How many a storm has swept over it [the marriage] . . . and still it continues green and fresh, and throws out green shoots, from which I can with gratitude to God, acknowledge that much good will yet be engendered for this world' (195). But he fails to discuss the first part of this, concentrating instead on Albert's various humanitarian activities, which he links throughout to his Lutheranism and his Germanic personality.

The latter, he makes clear, Albert retained till the end: he spoke to Victoria and their children only in German, his trusted advisers were German, and his last words from his death-bed were German. Albert remained, in Stewart's words, “a foreigner at heart” (105). No wonder then that the British people continued to regard him as such. Yet, by the end of his foreshortened life, he was well-regarded for his numerous social and cultural works, and his wife certainly thought that he had raised the status of the English monarchy. She wrote to their uncle, Leopold of the Belgians, “For what has not my beloved and perfect Albert done? Raised monarchy to the highest pinnacle of respect, and rendered it popular beyond what it ever was in this country" (170, Victoria's own emphasis).

Left: the Albert Memorial Chapel, Windsor Castle, with elaborate marble decoration by the sculptor Henri de Triqueti. "Another striking example of Albert's idealised image is the marble resting effigy of the Prince with armour and broadsword" here (Stewart 216). Right: Frogmore Mausoleum, Home Park, Windsor, where Albert and Victoria "now rest side by side" (Stewart 208).

A shadow falls, however, even on Stewart's generally bright picture of his subject. For some time now, the Prince had been suffering from various physical ailments, especially stomach cramps. Not long after the anniversary mentioned above, he fell seriously ill, and died at the age of 42. The cause given was typhoid, but people grew doubtful because it was not prevalent at that time. Queen Victoria added to the suspicions by adamantly refusing any post-mortem examination. Perhaps he had been suffering from some form of cancer, but, of course, this cannot be conclusively proved now. Despite the speculation surrounding it, his death not only threw Queen Victoria into inconsolable grief and perpetual mourning, but to some extent infected her subjects too. The public subscribed to Albert memorials all over the country and in the dominions, and “Albert” pubs, schools, hospitals and roads sprang up everywhere. In fact, “after the Prince's death there arose a cult of Albert that saw a proliferation of testimonials even greater in number than any erected to Wellington and Nelson” (214).

They say that behind every successful man is a strong woman. Stewart, on the other hand, has convincingly shown the enlightened man behind Queen Victoria's eminently successful reign. Explaining in detail Albert's contributions to the many aspects of life in his adopted country, he accepts the Queen's own judgement that Albert “raised the British monarchy to the highest prestige it had ever enjoyed” (217). This celebratory account is therefore much closer to earlier hagiographies like Edith Kenyon's of 1887, Albert the Good than to Helen Rappaport's recent Magnificent Obsession: Victoria, Albert and the Death that Changed the Monarchy, which analyses his relationship with his wife, and explores a wealth of archival material as well as the now-familiar secondary sources. But Stewart's book is not without value. It does exactly what it sets out to do, usefully confirming and illustrating the Prince Consort's actual achievements, and amply demonstrating that, even if he was largely powerless in government matters, he established the role of the modern constitutional monarchy by creating "the template for royal benevolence" (228). There is no doubt that Albert did contribute hugely to the success of his wife's reign — though we might not go so far as to suggest, as Stewart does, that the age could more appropriately be called "Albertine" than "Victorian" (5)!

Source

Stewart, Jules. Albert. London & New York: IB Taurus, 2011. 276 + xipp. £19.99. ISBN 9 780752 458533.

Other References

James, Robert Rhodes. Albert Prince Consort. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1983

Library of Congress Digital Gallery: photomechanical prints, c.1890-1900, of Coburg, LG-DIG - ppmsca - 01084 and Rosenau, LG-DIG - ppmsca - 01133. Web. 12 April 2012.

Lynch, Michael. Scotland: A New History. New ed. London: Pimlico, 1992.

Strachey, Lytton. Queen Victoria. London: Chatto & Windus (Phoenix Library), 1928.

Last modified 12 April 2012