Ray Dyer traces Tennyson's growing importance to Lewis Carroll, as he came to fill the role of father-figure, as well as becoming the younger writer's admired "poet-bard." Note the form of multi-volume citations below. Diaries, I: 51-52 note 1 appears as follows: Diaries 1.51-52n1. [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them, and for more information about them where available. — JB]

Part One: The Overtures, 1832-57

1832. Birth of an obscure and apparently inauspicious third child and clergyman's first son, who would later become famous as author Lewis Carroll. The newly established Cambridge scholar and burgeoning poet, twenty-three year old Alfred Tennyson, also a lowly placed son of a clergyman, had shared time at the university with Edward Fitzgerald, William Thackeray, and the tragic Arthur Hallam. This year saw publication of Tennyson's collected Poems. His Poems Chiefly Lyrical had already appeared in 1830. Others sharing 1832 as birth year included American writer Louisa May Alcott; the later Cambridge scholar, sceptic and editor of the Dictionary of National Biography Sir Leslie Stephen, and the Oxford Newdigate Prizewinning poet, Sir Edwin Arnold. Those leaving the world of 1832 included Goethe, literary doyen Sir Walter Scott, and Scott's own favoured Realist poet George Crabbe.

Mrs Dodgson, Carroll's mother, from a

silhouette. Source: Collingwood 13.

1834. Tennyson apparently has a 'first love' relationship with Rosa Baring. The theme of deep first loves will return in his later poetry [1847], and then later will touch Lewis Carroll [1855]. Here, meanwhile, Carroll as a two-year old is already the undisputed 'darling Charlie' of his own dear mother.

1842. Carroll as a home-schooled boy in a matriarchal family, now aged ten, passes his final summer close to Cheshire's ancient Daresbury Church, with its fascinating walls showing carved acrostics. Tennyson publishes a second volume of his Poems and is now established and famous. One of his new verses, "The Gardener's Daughter," shows a reverence for long female hair, and would apparently later help shape Lewis Carroll's lifelong attachment to this and related "wild" romanticisms. The rather different positive optimism of Tennyson's "Locksley Hall." which ""…dipt into the future, far as human eye could see, / Saw the Vision of the world, and all the wonders that would be," appears to have also influenced the complex mind of Lewis Carroll, who when more mature and a decade older [1851] would be sure to visit the Great Exhibition.

Lewis Carroll and his family at Croft Rectory, probably by Robert Wilfred Skeffington Lutwidge, c.1858-1862, courtesy © National Portrait Gallery London (NPG P32).

1843. The novelty of railway travel removes Carroll and family to the North Riding of Yorkshire, where his strongly Augustan and near omnipotent father becomes Rector of Croft, and eventual Archdeacon of Richmond and a Canon of Ripon Cathedral. Early railway maps show Croft Spa, before the popular preferences for Harrogate and Ilkley. Tennyson presents the Romantic poem Morte d'Arthur, further immersing "all England," and more especially young Carroll, in the abiding British Arthurian legends.

1847. Carroll was by now into year 2 of his 4-year 'rite de passage' as a young teenage boarder at Rugby School: shades of the great Dr. Arnold, and now Dr. Tait - a later Archbishop of Canterbury - for the all male pupils to further internalise as powerfully stern examples of surrogate paternalism and cultural rules. Tennyson published his evocative work The Princess, whose hauntingly romantic-melancholic line, "Deep as first love, and wild with all regret" (IV, First Song, v4; see the entry for 1834 above) would later also captivate as a personal revenant the then twenty-three-year old Lewis Carroll.

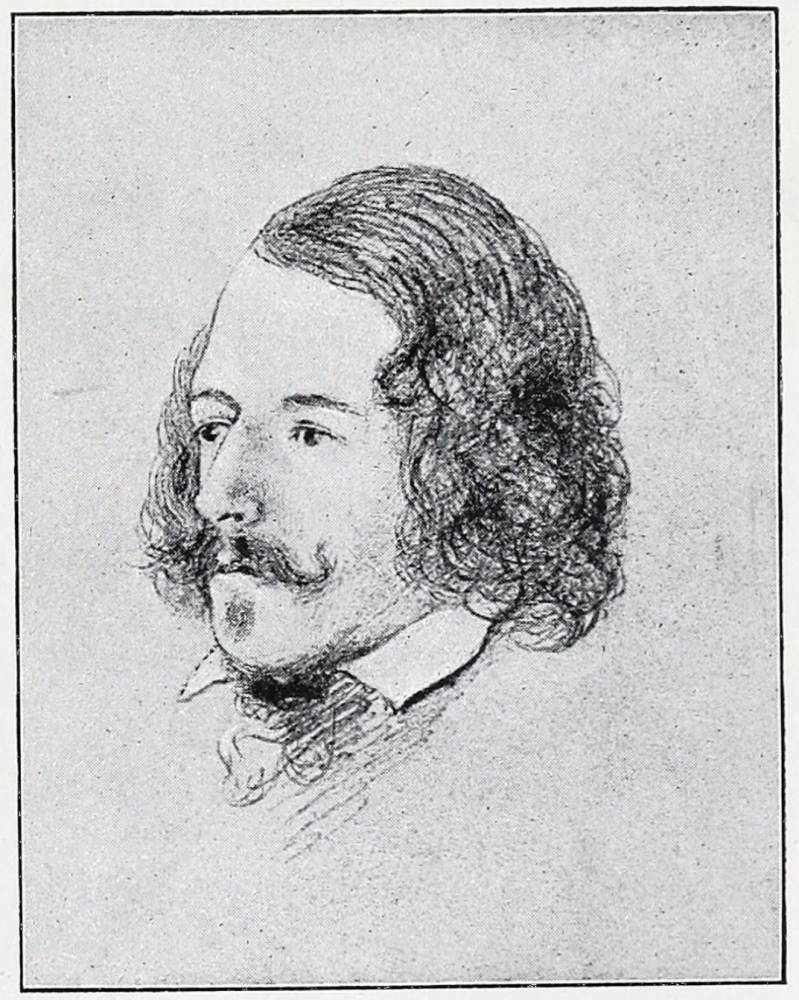

Tennyson, drawn by Richard

Doyle, c.1850.

1850. This year saw the death of Poet Laureate Wordsworth, and the accession of the new Laureate Tennyson. Carroll, cramming at home with his father-tutor before being accepted by Christ Church College, Oxford, was worked hard at Maths and Greek, Latin and the Classics, his father's original subjects. The eighteen year old student nevertheless found time and a creative outlet in the production of his by-now polished home-magazines for his younger siblings. "The Rectory Umbrella" was illustrated with his cover design of a rustic bard as poet and editor, an early indication of his deeper leanings. The year saw published - at that time anonymously and seventeen years deferred - Tennyson's heartfelt and melancholy work In Memoriam, marking the tragic early death of his close friend Hallam. Who will not recall the famous line "Ring out the old, ring in the new" (cv)? A decade later [1862] this requiem tale would attract the early pioneering indexing efforts of Lewis Carroll, aided in the intricate task by his meticulous and devoted sisters. The mid-century landmark witnessed the death of Balzac; and the births of Robert Louis Stevenson, Maupassant and General Kitchener.

1851. On 24 January Carroll entered Christ Church Oxford where he would remain in residence for the ensuing 47 years. Within days he is recalled home upon the death of his beloved mother, and three weeks later he returns to college. Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley had also died, towards the end of Carroll's mourning period. By summer that year he was visiting London, to his Putney cousins and the Great Exhibition of The Wares of Industry of All Nations. Third edition of Tennyson's The Princess. Tennyson's poem Mariana appears to have influenced artist John Millais, whose painting by the same name was exhibited at the Royal Academy that year, and also at Oxford in the house of art-collector Thomas Combe of the University Clarendon Press, and again in Merton College Chapel. Combe was a friend of Millais, and would soon become known to Lewis Carroll (Diaries 2: 75n151, 3: 33n51) who was also a keen art lover. It seems more than likely that Carroll would have known both Tennyson's poem and the eponymous picture, from any or all of his familiar venues noted above.

Christ Church College, Oxford,

by Vernon Howe Bailey, 1902.

1852. Studying at Oxford University, Carroll would inevitably be involved in the events surrounding the death of the Duke of Wellington, quintessential British hero and Chancellor of the University. Poet Laureate Tennyson produced his Ode to the Duke later that year, "With an empire's lamentation" (v.1). In December, as was his custom, Carroll's father presented his first-born son with a printed copy of his most recently-published church sermon. Entitled "Ritual Worship" and preached at the consecration of the church of St. Thomas in Leeds, it was infused with the High Church Ritualism which both Lewis Carroll and Tennyson would come to replace with a 'broader' view of life, one altogether less strict in both vestments and social practice. Carroll's internalised paternal presence was already seeking other avatars.

1853. Lewis Carroll, still the unknown Oxford undergraduate Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, completed his own poignant early romantic-melancholic poem, "Solitude," widely held by Carrollians to have been for his departed mother. Dated 16 March it formally presents his aspirations as a poet: "Here may the silent tears I weep / Lull the vexed spirit into rest, / As infants sob themselves to sleep…"; and with lines on the "golden hours of Life's young spring… / Thou fairy-dream of youth" (v.9), and "To be once more a little child / For one bright summer-day" (v. 10). The "golden" mood would surface again in his most famous book's opening frame-poem [1865], and he would there even strive to improve upon the generative [1850] line of his now adored Tennyson. "Solitude" would also be made part of Carroll's very last work published in his lifetime [1898], thereby closing at various levels the circle of his life as an aspiring Romantic poet. For his loyally persistent attempts to "close the circle" and attain closure with Tennyson, see [1862, 1871, 1892].

1854. Tennyson's Twickenham home had become increasingly plagued by passers-by and well-wishers intent upon lionising the Laureate, much to the latter's distaste. Tennyson reacts decisively, and this year sees him and his family move to live at Farringford on the south of the Isle of Wight. Carroll continues as an obscure Oxford and Christ Church undergraduate, returning to northerly Croft Spa between term-times.

1855. Carroll completes his B.A. course and begins his formal profession as a Christ Church Maths Lecturer. Tennyson's long narrative love poem Maud arrives in Carroll's hand at northerly Croft during the August of his long break from Christ Church, and is read in one day. He commended it to his journal with the borrowed phrase "Then life is not so bitter,/ But a smile may make it sweet," though he was also critical of the Laureate for repetition of certain phrases. In September he read the poem again and remarked upon its "true passionate poetry." composed with "the inspiration of a first love," (Diaries 1: 134) - probably the same revenant he had already recognised in Tennyson's earlier poem [1847]. Other connections, between Tennyson's Maud and Carroll's use of concealment and disguise in the later Through The Looking Glass are here pertinent. The topical Crimean War news was closely followed by Carroll this year, and he pored over Tennyson's epic poem of "Balaclava," (Diaries 1: 54,72,119). In his latest home-magazine Misch-Masch , produced in the summer Long Vacation, his section on "Poetry for the Million," dated "Croft, Aug. 13, 1855," dedicates the magazine to the "Spirit of the Age" and the Vanguard of "the Great March of Reform," ideas almost certainly tinged by Tennyson's [1842] "Locksley Hall," and by the Great Exhibition [1851].

Agnes Weld as Little Red Riding Hood, 1857.

1857. First meeting with Tennyson. Tent Lodge, Lake Coniston, English Lake District. During the latter half of this year we find Lewis Carroll now freely using his new pen-name in contributions to the humorous The Train magazine. His calling-card meanwhile preserved his legal name and status as a Christ Church don. In August, at Bishop Auckland in northerly County Durham, home of his father's friend Bishop Longley, late of Ripon and now of Durham, he met socially a Mrs. Weld, née Sellwood (b. 1814), and soon discovered her to be familiar with many of the literary celebrities of the day, and sister-in-law to the Poet Laureate (Diaries 3: 87 & n136, passim). The daughter, Agnes Grace Weld (b. 1849), who would become a lifelong friend of Carroll's, was soon photographed dressed as Little Red Riding Hood and part of Carroll's new hobby of wet-plate collodion photography. Carroll was careful to provide a developed copy not only for the girl's mother, but also for her uncle, Tennyson. By late August Carroll heard from Mrs. Weld that the photographs had arrived safely, and that "Mr. A. Tennyson" had pronounced the portrait of his niece "indeed a gem" (3: 89 & n138). In September, based upon information gained, Carroll holidayed in the English Lake District and took the opportunity of passing by Tent Lodge, Coniston, where he knew the Tennysons were staying, in the house of their friends the Marshall family of Ambleside, Westmoreland and Headingly, Leeds (Diaries 3: 108 passim). Upon sending in his card, with the hastily scribbled words "Artist of Agnes Grace" [the Laureate's niece], he was kindly received by the family. By the end of the month his persistence with the still early and attractive new art of photography had enabled him to provide likenesses of Tennyson, his wife and their two small sons, Hallam (b. 1852) and Lionel (b. 1854). Agnes Weld and her mother continued to attract Carroll's frequent attention, with his journal noting eight further entries for the young girl and five for the mother to April 1858. Tennyson received fifteen entries over the same period. The Marshall family-friends of the Tennysons would also be adopted by the socially fluent Lewis Carroll, with photography of their captivating daughter, Julia Marshall, born 1845. Carroll was also familiar with their other home in elevated north Leeds, where the family had factories on the lower industrial bank of the River Aire. Carroll made regular railway-journeys between Croft and Thirsk-Harrogate-Leeds-Doncaster-Oxford. As late as 1888 Carroll would be making London calls (in vain) to the house of this then married daughter, Mrs. Edward O'Brian, JP (8: 412).

Note: A considerable break occurs in the extant private journals of Lewis Carroll, from April 1858 to May 1862. Those missing, lost or destroyed journals are partially restored by the editor of Diaries (4: 4 passim), though often only as regards major and regular annual events, and backed up in Carroll's voluminous correspondence or similar "hard" sources, including the Farringford Journal of Emily Tennyson, 1853-1864. The especially controversial nature of certain features of Lewis Carroll's life throughout those 'missing' years - the difficulties over his ordination beyond the rank of deacon; the arrival of the oldest Liddell sister, Lorina, at the then marital-sensitive age of 12 to 14; and the generative period here of whatever difficulties would by late 1864 have shattered the close relationship which Carroll clearly sought from his idol Tennyson - all these considerations leave doubts as to any innocent accidental loss of so much and at such a crucial period of Carroll's private innermost thoughts, hopes and feelings, which he so often committed into his private journals. Further speculation, as to who might have been motivated to destroy the journals and why, must remain beyond the scope of the present work.

Links to related material

- Part Two, 1858-64: The Amicable Years

- Part Three, 1865-76: A Melancholy Interregnum

- Part Four, 1877-89: A Watershed and Acceptance

- Part Five, 1889-98: Final Glances

- A Lewis Carroll Chronology, 1832-1898

- An Alfred Lord Tennyson Chronology

Bibliography

Carroll, Lewis. Lewis Carroll Diaries. The Private Journals of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. Ed. Edward Wakeling. Vols.1 to 3 & 8. England: Lewis Carroll Society, 1993, 1994, 1995 & 2004.

[Illustration source] Collingwood, Stuart Dodgson. The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll. New York: Century, 1899. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Library of Congress. Web. 6 June 2022.

Created 6 June 2022