In transcribing the following paragraphs from the Internet Archive online version, I have expanded the abbreviations for easier reading and added paragraphing and subtitle South The illustrations are in the original. The Gazetteer has 1856 on the title-page for this volume, but the statements in this essay date it to 1851, and this entry has particular interest because it presents Liverpool at mid-point in the century, when the city had already grown but had yet to reach its size later in Victoria’s reign. — George P. Landow]

St. George’s Hall and Lime Street Railway Station, Liverpool. “From an old drawing.” [Follow for modern photographs of the hall and its sculpture.]

LIVERPOOL, a parliamentary and municipal borough and seaport in England, in the county of Lancaster. It is situated on the right bank of the bank Mersey, about 4 miles from its confluence with the Irish Sea; lat. (Observatory) 53 24 48" North; longitude 3 West (R.) It stands partly on flat ground along the margin of the river, and partly on a gentle acclivity. Its utmost length, from North to South, is upwards of 4¾ miles greatest breadth, East to West, rather more than 2½ miles. Area, 5002½ acres.

The principal streets diverge more or less directly from a central area, in which stand St. George’s Hall and St. John’s Church. In the older parts of the town the streets are narrow, and ill built; but in the more modern portions, particularly in the East, they are wide, airy, and well paved. Here also occur some handsome squares and crescents, lined with elegant mansions, chiefly of brick, roofed with slate.

The town is well lighted with gas, and supplied with water at present from wells sunk in the new red sandstone on which the town is built. There are seven wells, the greater part of the water from which is pumped into a reservoir at an elevation of about 200 feet above the lowest part of the town. From this reservoir it is distributed under high pressure; and there being an abundance of hydrants in the streets, especially in the warehouse districts, fires are easily extinguished by the application of hose and jet. The result is, that serious destruction of property by fire is now unknown. The quantity of water distributed daily amounts to 5,750,000 gallons. At present works are in progress for obtaining an increased water-supply from the hilly district of Rivington, about 26 miles from Liverpool. Reservoirs are there in course of construction, which, when completed, will form great lakes of the aggregate length of 6 miles; and from these, after being filtered, the water will be conveyed to the distributing-reservoirs in the town in iron pipes, 44 inches diameter.

Major Public Buildings

The most important public buildings are the Townhall, Exchange Buildings, Revenue Buildings, and St. George’s Hall. The Townhall is an elegant Grecian structure, which was founded in 1749; a handsome dome, supported by Corinthian pillars, and surrounded by an open gallery, rises from the centre of the building; within are a saloon, drawing-rooms, ball-rooms, banqueting room, and refectory, all splendidly furnished, forming, probably, the finest suite of entertaining-rooms in the kingdom. The Exchange Buildings form three sides of the square, of which the Townhall constitutes the fourth; it has three interior facades; an arcaded basement, with a walk of 15 feet in width, extends along each of the façades, and is surmounted by a range of Corinthian pilasters, supporting a handsome cornice and balustrade; in the East wing of the building is a spacious news-room. The Revenue Buildings, which comprise the Office of Inland Revenue, the Offices of the Commissioners of the Docks, and Post-office, cover an area of 6700 sq. yds., and have an extreme length of 467 feet, with a total height of 67 feet; lofty porticoes, each supported by eight Ionic columns, adorn the centre, and East and West fronts; the centre of the building is surmounted by a dome, lighted by sixteen windows, and ornamented round by pilasters. St. George’s Hall, which comprises also the Assize Courts, is a sumptuous building in the Corinthian style; the East façade, or the longer side of the building, is 420 feet long; the advanced colonnade in the centre is 200 feet in length, and, being recessed, forms within an ample sheltered ambulatory 26 feet in depth. The North portion of the plan forms a concert-room, capable of accommodating 1200 auditors, making the entire extent, from North to South, 500 feet. The other structures, exclusive of the churches, deserving of notice, are the Royal Bank buildings, the North and South Wales Banks, the Stations of the London and North Western, and the East Lancashire, and Lancashire and Yorkshire Railways, Liverpool Apothecaries Hall, Adelphi Hotel, Infirmary, Collegiate Institution (photograph), Philharmonic Hall, and Lyceum. The Theatre and Amphitheatre are also both respectable structures. Few towns are so well supplied with market-places as Liverpool, there being about a dozen of them in various localities; several of them are spacious, airy, covered structures that of St. John’s, ⅛ mile long, by 45 yds. wide, being specially worthy of mention; they are probably better supplied with all kinds of provisions than any other markets in the kingdom.

Churches, Chapels, and Charitable Institutions

There are altogether 45 churches and 35 chapels in Liverpool, besides numerous other places of worship; the former comprising two churches belonging to the Scotch Establishment, three to the Free Church, one to the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland, one Irish Presbyterian, and a church of the Holy Apostles. The chapels include five Wesleyan, two Wesleyan Association, five Independent, three Methodist, right Roman Catholic, four Baptist, three Unitarian, one Friends meeting-house, two Jews synagogues, one Sandemanian, one floating chapel, and one New Jerusalem; and to almost every place of worship a school is attached. Many of the churches and chapels are exceedingly handsome buildings. Amongst the more remarkable for their architectural beauty are St. Francis Xavier’s and St. Mary’s Roman Catholic churches, the church for the blind, St. Luke’s, Great George Street chapel, St. George’s Presbyterian church, Baptist chapel, St. Andrew’s Scotch church, St. George’s, St. Catherine’s, St. Michael’s, St. Martin’s, and the Hope Street Unitarian chapel.

Liverpool is remarkable for the number of its charitable and benevolent institutions, and for the suitableness of the buildings devoted to these purposes; there being no fewer than fifteen or sixteen different establishments of one kind or another for the alleviation of distress, besides three or four charity schools. The principal are the Infirmary, Fever Hospital, Lunatic Asylum, Lock Hospital, and three extensive public bathing establishments, erected by the Corporation, one of which is amply supplied with filtered salt-water, and the others with pure spring-water. To one of these establishments a public washing house is attached; and there is a separate public washing-house in another locality. There are likewise many religious societies. The educational institutions comprise the Royal Institution, the Mechanics, the Collegiate, and the Medical Institutions. Associated with these are the news rooms, among which tho Athenaeum and Lyceum hold the highest station, and have extensive libraries connected with them. There is also the Free Public Library, and Derby Museum. The schools consist of the Corporation, National, and Infant schools, and of a vast number belonging to the various religious denominations. The principal places of amusement are the Theatre Royal, the Royal Amphitheatre, the Royal Liver Theatre, the Royal Adelphi, the Philharmonic Hall, one of the finest concert-rooms in Europe; Music Hall, Wellington Rooms, the Zoological and Botanic Gardens; and the race-course at Aintree, where meetings are held in May and July.

Liverpool’s Docks

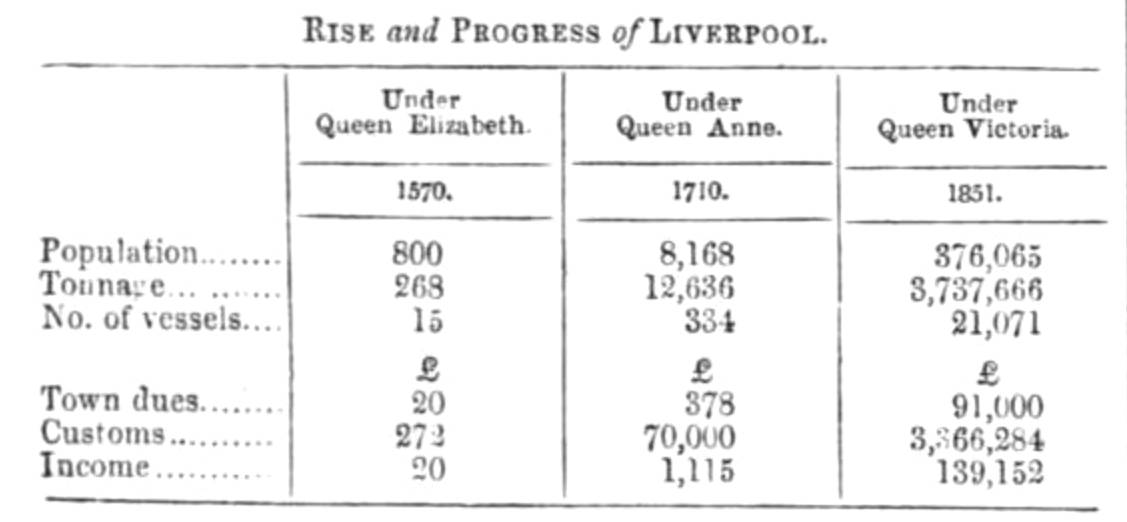

But the most remarkable feature of this great seaport is the number and magnificence of its docks, corresponding with the extent of its vast commerce. All of these lie along the margin of the river, or between it and the town; most of them parallel with the Mersey, but some of them at right angles to it. There are, in all, 30 docks, of three different kinds, namely, wet docks, dry docks or basins, and graving docks. The first are principally for ships of great burden, employed in the foreign trade, such vessels floating in them at all states of the tide, the water being retained by gates; the dry docks, so called because they are left dry when the tide is out, are chiefly appropriated to coasting vessels; and the graving docks, which admit or exclude the water at pleasure, are adapted to the repair of ships, during which they are kept perfectly dry, and when completed, are floated out by admitting the tide. The extreme length of the river wall, which fronts the line of the Liverpool docks, is 5 miles The total water area amounts to 200 acres; of this 179 acres are wet docks, and 21 acres dry basins; and the total quay space exceeds 14 miles The four largest docks are the Huskisson, Prince’s, Queen’s, and Brunswick docks. The first covers an area of 15 acres, 993 sq. yards; length of quay frontage, 1122 yards; depth of water, 27 feet; the second nearly 12 acres; the third above 10 acres; and the fourth above 12 acres. Nearly 12,000,000 have been expended in Liverpool, and more than 12,000,000 on the river Mersey, in securing safe anchorage, and the most perfect port accommodation ever formed by the skill of man. The following Table of the number of vessels that have entered the docks at various dates, and of the progressive increase of the dock dues and customs, exhibits, in a very clear manner, not only the great extent of the shipping of the port, but the extraordinary rapidity with which it has increased since the commencement of the present century. The decrease of the customs receipts in recent years is mainly due to the abolition of the duty on cotton and wool.

In the value of its foreign exports, and the extent of its foreign commerce, Liverpool is now the greatest port in the British empire, and is consequently the first port in the world. In 1850, the foreign exports amounted to nearly £35,000,000 sterling, or considerably more than one-half of the total value of the exports of the three kingdoms for that year, and more than twice that of London. During the five years ending with 1850, the increase of the exports of Liverpool has been from £26,000,000 to nearly £35,000,000, while that of London has been from about £11,000,000 to rather more than £14,000,000.

The quantity of foreign and colonial produce imported into London, in 1850, was 374,947 tons; into Liverpool, was 1,384,353; into Hull, 639,823. The value of foreign and colonial produce imported into London that year was £43,183,821; of that imported into Liverpool £37.404, 400. The value of the principal articles imported into the latter was,

| Cotton | £15,730,800 | Grain and flour | £5,198,796 | Sugar | £2,4850,00 | Tobacco | £3,388,000 | Sheeps’ wool | £1,380,000 | Tea | £21,831,000 | Hemp | £770,640 | Timber | £ 725,000 |

The principal articles imported in 1849-51 are shown in this table.

The cotton trade of Liverpool, as will be seen from the foregoing statement, forms one of the most important branches of its general commerce. In 1851, the total imports of that article amounted to 1,748,946 bales; while, in 1785, the total amount imported was five bales; which, in 1811, had increased to 98,752 bales; and, in 1841, to 1,164,269 bales. The discovery of the gold of California has recently given Liverpool a great trade in the precious metals, which it did not formerly possess. In 1851, the gold and silver imported into that port from the United States were of the value of £6,091,433. The Irish and coasting trade is also very large, and, in 1850, gave employment to 896,168 tons of steam tonnage, and 515,836 tons of sailing vessels. The grain, &c., imported from Ireland, in 1849-51, was as follows:

The weight of the goods, merchandise, and produce of all kinds which passes through the port of Liverpool yearly, is at least 6,000,000 tons: the shipping employed in transporting it amounted, in 1850, to 6,011,870 tons. The export of linen is chiefly through the port of Liverpool, from which there was shipped, in 1850, 122,397,457 yards; and of yarn, 18,559,318 pounds; and being the chief port for Lancashire, Cheshire, and Yorkshire, immense quantities of the textile fabrics of these counties, intended for foreign parts, pass through it, to the extent, it is estimated, of 28,000,000; as do also of the cutlery of Sheffield, and hardware of Birmingham; the iron of Staffordshire, Yorkshire, and North Wales, in the form of rails, bars, hoops, and sheets; and the earthenware of the first-named county, of which 61,528,196 pieces were shipped, in 1849, to various parts of the world. Salt, and the alkali called soda-ash, likewise form important items in the commerce of Liverpool. Of the first, 445,633 tons, and of the second, 44,407 tons were exported in the year 1850. In 1850, the value of the beer and ale exported amou itcd to 558,794; and, in 1851, to 577,874. Liverpool has also been, for some years, the great point of departure for emi grants from Great Britain and Ireland. It has now also become the place of emigration for Germans who find it cheaper to sail from this port than from their own country. The following Table shows the progressive increase of this trade since 1831:

| Years. | Number of Emigrants. |

| 1833 | 10,888 |

| 1836 | 32,845 |

| 1840 | 40,359 |

| 1845 | 55,577 |

| 1848 | 131,121 |

| 1849 | 153,905 |

| 1850 | 174,187 |

| 1851 | 206,015 |

What Liverpool Manufactures

The manufactures of Liverpool consist chiefly of shipbuilding, sugar refining, iron and brass founding, brewing, glass staining, alkali making, rope making, and steam-engine making. The manufacture of soap is more extensively carried on there than in any other town in the kingdom, as is that, also, of chronometers, watches, and watch movements; large quantities of the latter being annually exported. There is a large cotton manufactory near the town, also several wind-mills, and steam-engines for grinding corn, colours, dye-woods, &c., and numerous large manufactories of chain cables, anchors, &c. By railway, Liverpool is connected with all the principal towns and ports in the kingdom; and its trade is further facilitated by an extensive net-work of canals, connecting it with the great seats of manufacturing and mining industry. It has regular communication, by steam- vessels, with Glasgow, Belfast, Londonderry, Dublin, Cork, Holyhead, and nume rous places on the coast of England and Wales; with Havre, the Mediterranean, and New York, Boston, Halifax, Central America, &c.

The suburbs of Liverpool are very extensive and beautiful, being thickly covered with neat rows of houses and handsome villas, and are rnpidly increasing in population and importance. Within the parliamentary borough are included the townships of Everton, Kirkdale, West Derby, and Toxteth Park. In connection with these maybe named the important and rising places in Cheshire, on the opposite side of the Mersey, and connected with Liverpool by steam ferries., plying every quarter of an hour; and in which many of the Liverpool merchants reside. They are Seacombe, Woodside, Monk’s-ferry, Birkenhead, Tranmere, Rockferry, Eastham, Egremont, and New Brighton; between which and Liverpool there passed by the ferries, in 1851, above 8,000,000 passengers. There are several cemeteries in the town and its vicinity, the most noted of which are St. James’s, the Necropolis, and St. Mary’s. These are laid out with taste, and kept in good order; and a chapel is appended to each, in which the funeral service is performed. There are also two parish cemeteries, and a Jews burying-place.

The corporation of Liverpool consists of 48 councillors, a mayor, and 16 aldermen elected by the council. The borough returns two members to Parliament; registered electors (1851), 17,316.

Public Health

Liverpool was formerly the most unhealthy town in England; but the vigour with which sanitary operations have been carried on of late years, more particularly since the local sanitary act of 1846, has done much to rescue the town from its unenviable notoriety. These measures, comprising sewerage, house-drainage, improved paving and surface cleansing, the regulation of lodging-houses and slaughter houses, the closing of unhealthy cellars, &c., have effected a marked improvement in the condition of the districts in habited by the working-classes; and to this must no doubt be ascribed the fact, that the mortality of the borough which, ten years ago, amounted (on an average of years) to 31 in every 1000 inhabitants, has recently fallen to an average of little more than 29 in the 1000.

Great as Liverpool now is, it is of but comparatively recent growth, and has therefore little or no history. Little more than two centuries ago, it was but a small fishing town, with lew houses, and still fewer streets. Of the progress of this great commercial port, the following table presents a curious and interesting epitome:

In 1644, Liverpool, then surrounded by a high mud wall, was besieged and taken by Prince Rupert, and shortly after retaken by the Parliamentary forces, under Sir John Meldrum. Seven years later, a second visitation of the plague carried off 200 inhabitants. In 1709, a wet dock was constructed, not only the first in Liverpool, but also in the kingdom. From this event may be dated the rapid extension of its commerce and population; though, as evidenced by the following Table, the greater portion of the increase of population has taken place since the commencement of the present century:

| Year. | Population. |

| 1700 | 5,010 |

| 1760 | 20,000 |

| 1801 | 77,653 |

| 1821 | 55,577 |

| 1851 | 376,065 |

Mrs. Hemans, the Rev. Leigh Richmond, and Dr. Currie, the biographer of Burns, and William Roscoe, were natives of Liverpool. (Sources for article: Picturesque Handbook of Liverpool; Baines, History of Liverpool; Local Correspondent).

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. 4 vol South London: Blackie & Son, 1856. Internet Archive online version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web.9 November 2018.

Last modified 13 November 2018