George Cruikshank and Phiz (Hablot Knight Browne), like Victorian painters such as Augustus Egg and W. Holman Hunt, used posters, maps, and especially well-known paintings within their own book illustrations to comment on the characters and situations they depicted. The pictures within their pictures include material from both high and popular cultures, which suggests that Victorian illustrators aimed at a middle-brow readership able to appreciate such visual allusions. As the realistic style of the New Men of the Sixties superseded the caricatural style of the earlier illustrators, book and magazine illustrations made only incidental use of such embedded images, which usually lack Hogarthian editorial and symbolic implications.

The Influence of Hogarth

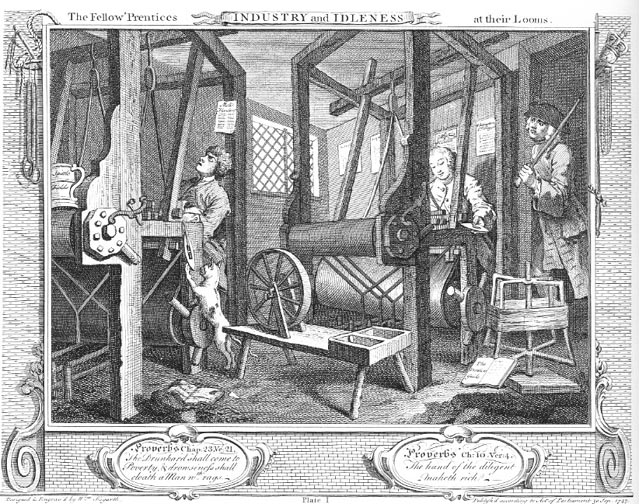

William Hogarth (1697-1764), whom many Victorian artist and critics believed to be the father of English painting, provided the inspiration for the use of such complex interplay of images within the picture space. Furthermore, his twelve-part series Industry and Idleness provided numerous examples not only of pictures and texts within the what we may term the main picture but also texts and symbols added to the engravings’s framing devices.

The Fellow Apprentices at their Looms from Industry and Idleness, I. William Hogarth (1697-1764). 1747. 10 3/16 x 13 3/8 inches. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Take, for example, the opening work in the series, The Fellow Apprentices at their Looms, where scriptural texts appear on the ornate shields beneath main image. The one beneath the apprentice at left reads, "The Drunkard shall come to Poverty & drowsiness shall cloath a Man [in] Rags" (Proverbs 23:21) while the one beneath the apprentice at right reads, “The hand of the diligent maketh rich” (Proverbs 10:4). Both texts, as it turns out, predict the fate of both young men by the series’ end, something hinted at by the texts Hogarth ingeniously places within the picture space. Whereas the good apprentice has nearby a book entitled The Prentices Guide and sheets tacked on the wall behind him have the words “Prentice” and “R Wittington Ld Mayor,” the one destined for a bad end works at his look with a tankard before him and a piece of paper with the words “Moll Flanders” behind. To complete the contrast of the two men Hogarth placed the good apprentice’s copy against a piece of equipment while the bad one’s lies tattered at his feet.

Not all of Hogarth’s works have this complexity, to be sure, and many employ pictures rather than texts within and without the picture space. In The Morning Levee, the fourth scene of Marriage à la Mode, which Hogarth first painted and then had engraved, Correggio's Jupiter and Io appears prominently above the young married woman listening to a man in clerical garb, who echoes a portrait on the painting's left side.

The Pre-Raphaelites and Their Associates

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, who made Hogarth one of their main heroes, employed his devices. John Everett Millais’s Christ in the House of His Parents thus includes various prefigurations of Christ, including the dove representing the Holy Spirit, plus tools representing the devices of Christ's agony and the palms His entrance into Jerusalem.

Christ in the House of His Parents. John Everett Millais. 1849-50. 34 x 55 in. Oil on canvas. Courtesy of Tate Britain, London. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Others associated with the PRB used these devices, too.

Past and Present I & III. Augustus Leopold Egg. 1858. Both oil on canvas, 25 x 30 inches and courtesy of Tate Britain, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Augustus Egg, a friend of Hunt’s, places a painting of a shipwreck immediately behind the husband in the first scene of the triple-series known as Past and Present in which the wife’s infidelity is discovered, and the third painting, which depicts the wife abandoned by her lover with her bastard child under a bridge, has posters hat comment on the woman's situation: As the Tate Britain commentary points out, “Directly behind her a poster (detail) advertises two plays at the Haymarket Theatre, Victims and The Cure for Love; another announces 'Pleasure Excursions to Paris.'”

Victorian Illustrators' Use of Pictures-within-Pictures

Hogarth also influenced Victorian illustrators, who embedded images in their magazine and part-publication productions to allude to well-known themes and characters: in particular, the Bible, Shakespeare, and classical mythology provided such illustrators with a rich trove of material for visual allusions through which to comment upon the fiction they were illustrating. The New Men of the Sixties, including George Du Maurier, Luke Fildes, and Fred Walker, and Fred Barnard, continued the practice of embedding visual material such as posters and paintings in their book illustrations, although not with the frequency of Phiz, Cruikshank, and Leech. Often, of course, paintings are merely the incidental furnishings of the well-appointed Victorian parlour, as in Fildes' At the Piano for Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood, in which family portraits above the piano establish the thorough respectability of Miss Twinkleton's school for young ladies.

Illustration for Cruikshank's Mr. Lambkin: by Mr. Lambkin . . . foolishly dashes into dissipation (1844).

Victorian illustrators also borrowed the practice of embedding pictures within pictures in their magazine and part-publication productions from eighteenth-century painter and print-maker William Hogarth (1697-1764). For example, Cruikshank's use of sporting images suggests the tone and subject of conversations in Mr. Lambkin, finding that he has been variously and thoroughly befooled, foolishly dashes into dissipation in his own Hogarthian progress, The Bachelor’s Own Book; Or, The Progress Of Mr. Lambkin (Gent.), in the Pursuit Of Pleasure And Amusement (1844), a satire on the shallow materialism of the English bourgeoisie. In this particular illustration, Cruikshank captures the moment when the besotted company of six are belting out the lyrics of the anacreontic song with boozy enthusiasm. The sporting pictures on the wall, of pugilists and horse-racing, establish the raucous atmosphere of these bachelor apartments. The race pictured may in fact constitute a topical allusion since the four-mile Grand National handicap steeplechase at Liverpool had just been established in 1839. Although by the 1840s many of the traditional bloodsports such as cockfighting and wagering on sporting events had sharply declined as a result of new legislation and changing mores, horse-racing and boxing remained immensely popular, continuing to attract thousands of spectators.

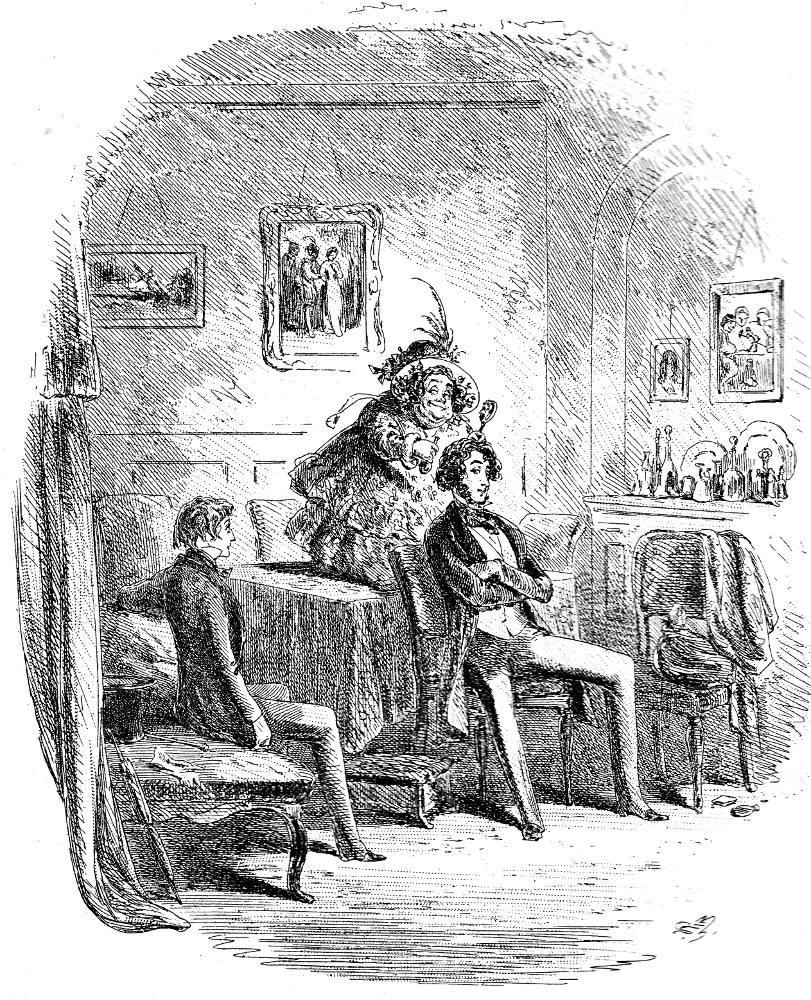

Illustration for Charles Dickens's David Copperfield by Phiz: I make the acquaintance of Miss Mowcher (December 1849).

The satiric tradition that Cruikshank, Phiz, and other Victorian illustrators inherited from Hogarth also exerted a powerful influence over such novelists as Charles Dickens, particularly in such early "progress" novels as The Adventures of Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress and the Pickwick Papers, in which the young novelist and his illustrators utilised both learned and popular iconography in the form of emblemmatic details as well as pictures-within-pictures. As Michael Steig notes in Dickens and Phiz, by the time that Phiz illustrated that later progress novel David Copperfield the writer and his illustrator exploited the ironic possibilities of embedded images in ways that raise questions of “artistic responsibility.” Did these signifying details originate with novelist or illustrator?

For example, in I make the acquaintance of Miss Mowcher Phiz includes what Steig calls “three emblematic details: a ship in a storm (probably representing Emily's impending fall but also conceivably foreshadowing Steerforth's death in a shipwreck), a comic reference to Miss Mowcher's size and performance in a print showing Gulliver performing for the Brobdignagians [sic], and a scene from Faust” (pp. 18-19). Some critics, like Anthony Burton, claim that Dickens directed Phiz to insert such emblematic details, but the fact that we can’t definitely assign authorship to either writer or artist demonstrates the problematic complexity of their relationship.

Two Biblical Allusions: The Magdalene and The Good Samaritan

Left: Martha, illustration by Phiz for Dickens's David Copperfield. Right: Cruikshank illustration Oliver recovering from fever for Dickens's Oliver Twist.

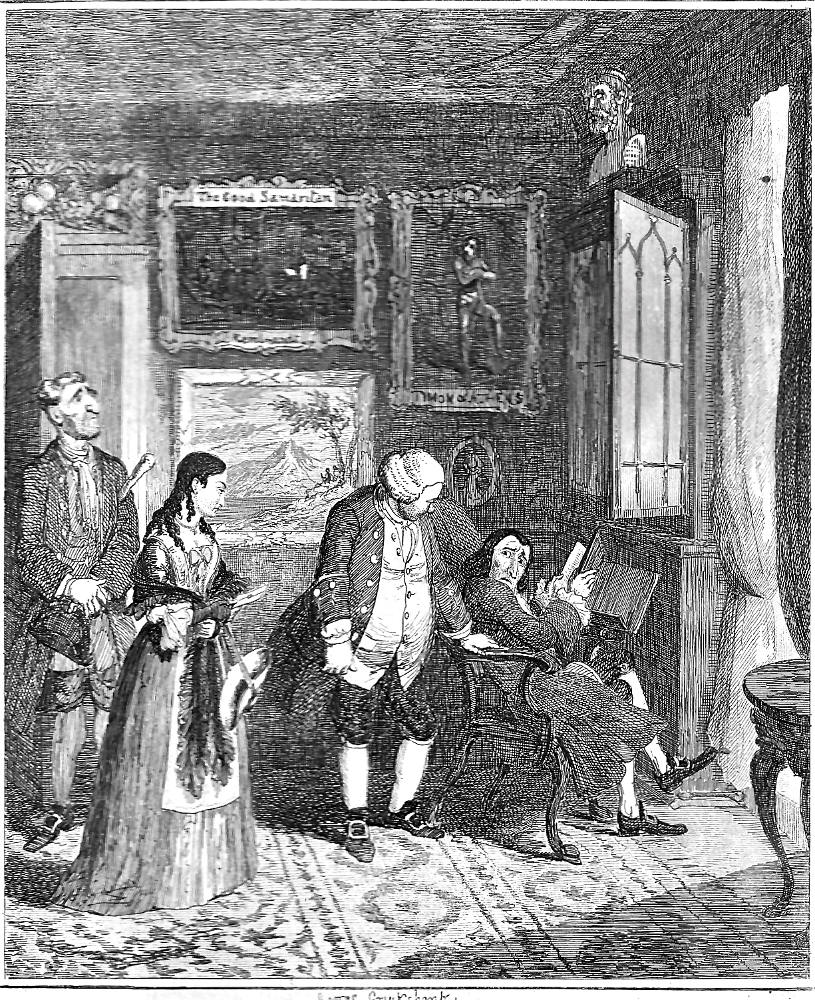

Whereas such embedded works of art are clear in their outlines in illustrations by Cruikshank and Phiz — for example, the painting of Mary Magdalene in Martha in Chapter 22 of David Copperfield, in The Miser's Daughter's fifth illustration, Hilda's Interview with Abel Beechcroft, Cruikshank identifies the meaning of the pictures largely through their captions rather than through their effectiveness as miniature facsimiles of cultural icons — that is, with appended texts rather than with recognizable images.

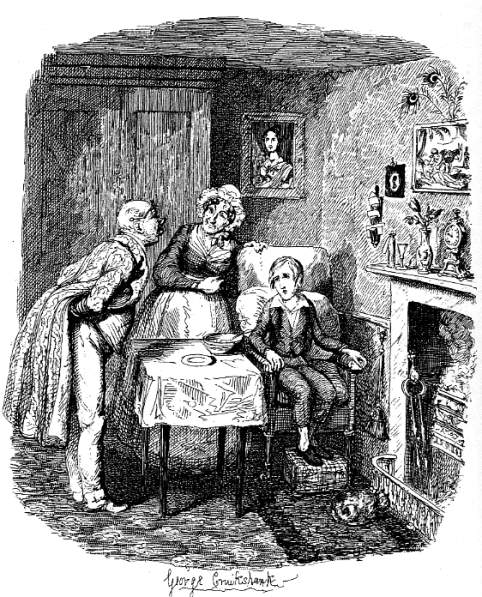

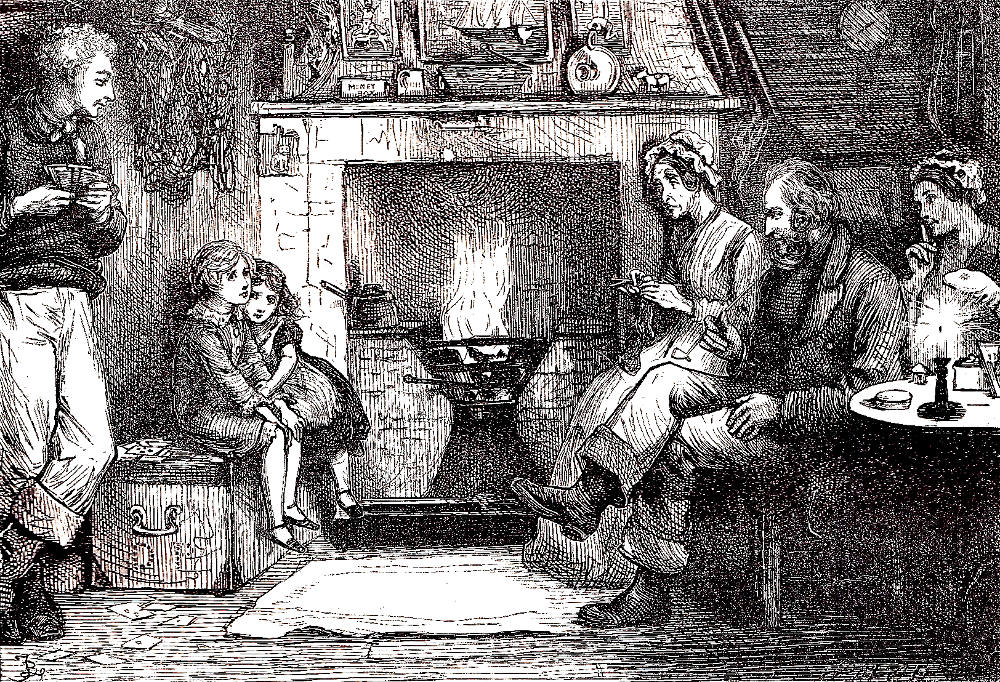

Victorian illustrators likewise often embedded references to such New Testament parables as that of the Good Samaritan, usually taking the cue from the authors with whom they were working. In illustrating novels by Dickens, which repeatedly utilize the figure of the Good Samaritan from the parable in St. Luke, Cruikshank depicted Mr. Brownlow as a genuine Samaritan and Fagin as a sham one. He underscored the Samaritan connection in Oliver recovering from fever in Oliver Twist by placing a painting of the Good Samaritan above the fireplace in Mr. Brownlow's parlour.

Cruikshank's treatment of the poor boy taken in and nursed back to health by the elderly bachelor and his kindly housekeeper, Mrs. Bedwin, is both theatrical and narrative; that is, the Regency illustrator has included all the elements that Dickens describes, including the feverish boy in his chair, Mr. Brownlow in his embroidered dressing-gown, the table, fireplace, and wardrobe (producing a rather crowded effect), and, above Oliver, the small portrait, a taken-from-the-life study which is complemented by the ornately framed oil painting above the mantelpiece of a suitable biblical analogue, the kindness of the Good Samaritan in Christ's New Testament parable (Luke, 10:25-37). Thus, the novelist and artist make clear that, by his treatment of the urban waif, Brownlow acts as a modern Samaritan to the virtuous Parish boy, a nineteenth-century equivalent of the ancient traveller set upon by brigands and left for dead.

Left: Hilda's visit to Abel Beechcroft, a Cruikshank illustration for Ainsworth's The Miser's Daughter (March 1842). Right: Fellow Travellers, a Phiz illustration for Dickens's Little Dorrit (October 1856).

The implicit commentary in Cruikshank's embedded Samaritan painting in The Miser's Daughter complements William Harrison Ainsworth's setting up the mysterious relationship between scholarly Abel Beechcroft and the inveterate miser, Mr. Scarve, in The Miser's Daughter. The viewer makes the connection between the New Testament parable and the backstory of the relationship between the miser and the classicist only later in the novel, so that the placement of a painting captioned The Good Samaritan functions as foreshadowing rather than immediate commentary.

In The Travellers, in Little Dorrit, Book the Second, "Riches," Chapter 1, "Fellow-Travellers," Phiz uses embedded images merely to clarify the setting, which is the refectory of a convent, Phiz has added a statue of the Virgin and the Child (left) and a portrait of Christ above the mantel of the fireplace. Thus, the picture is without the kinds of emblematic images that characterize his earlier work for Dickens and Charles Lever.

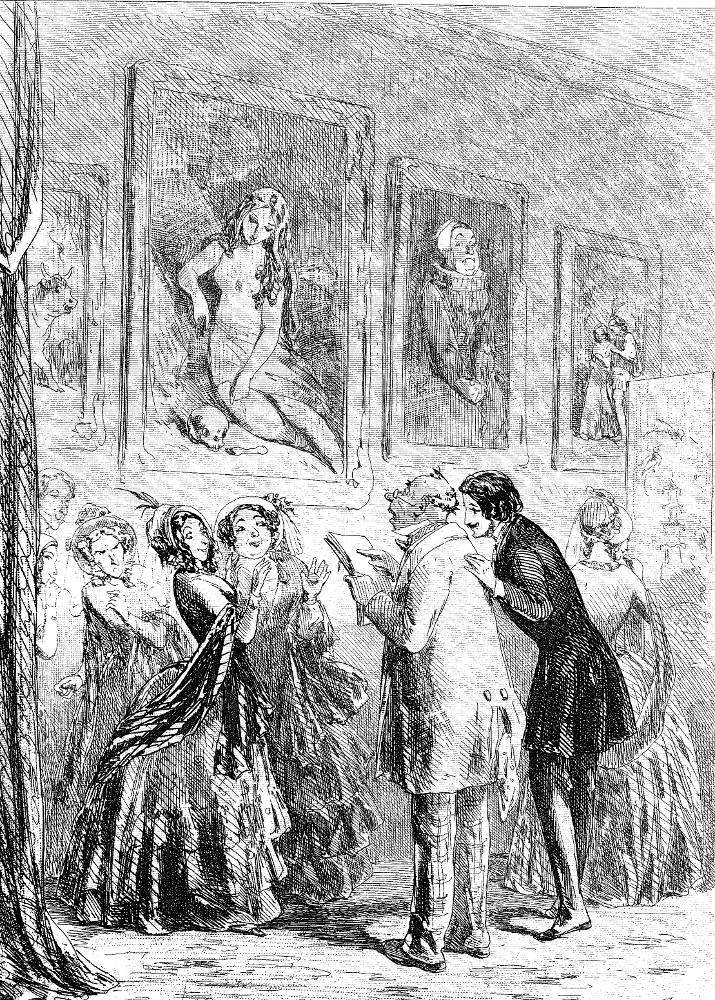

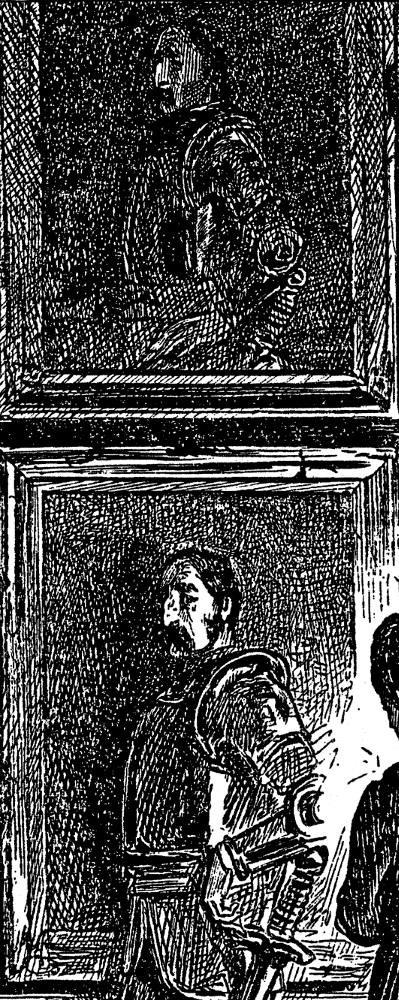

Two illustrations by Phiz of novels by Charles Lever: Left: The Picture Gallery — Sir Andrew Puzzled, an illustration for Roland Cashel (1849). Right: Warm Tea and Cold Reception for Barrington (1863)

For Warm Tea and Cold Reception Phiz deploys three embedded pictures, the most obvious being a painting of a stallion (centre) above the fisherman's self-invited guest, the Major. In the next illustration, Phiz uses an oddly-placed picture of a trout to complement the otherwise functional interior fisherman's cottage in The Accident. Phiz utilizes as his backdrop the entrance hall of "The Fisherman's Rest," a room characterized by fishing tackle and (somewhat incongruously above the lintel) either a picture of or a mounted specimen of a large fish. Many of the other interiors in this novel involve inset pictures of horseback riding to emphasize the sporting nature of the characters.In Lever's Roland Cashel the reader finds nothing remarkable about the oil paintings which Phiz places in the backdrop of The Picture Gallery — Sir Andrew Puzzled (1849); they merely constitute a visual language which the obtuse Sir Andrew cannot comprehend. These generalised images suggest that Lever took little interest in the subject of pictures-within-pictures, and made little use of them in the narrative. A more pertinent use of embedded paintings occurs in Leech's 1843 political cartoon Substance and Shadow.

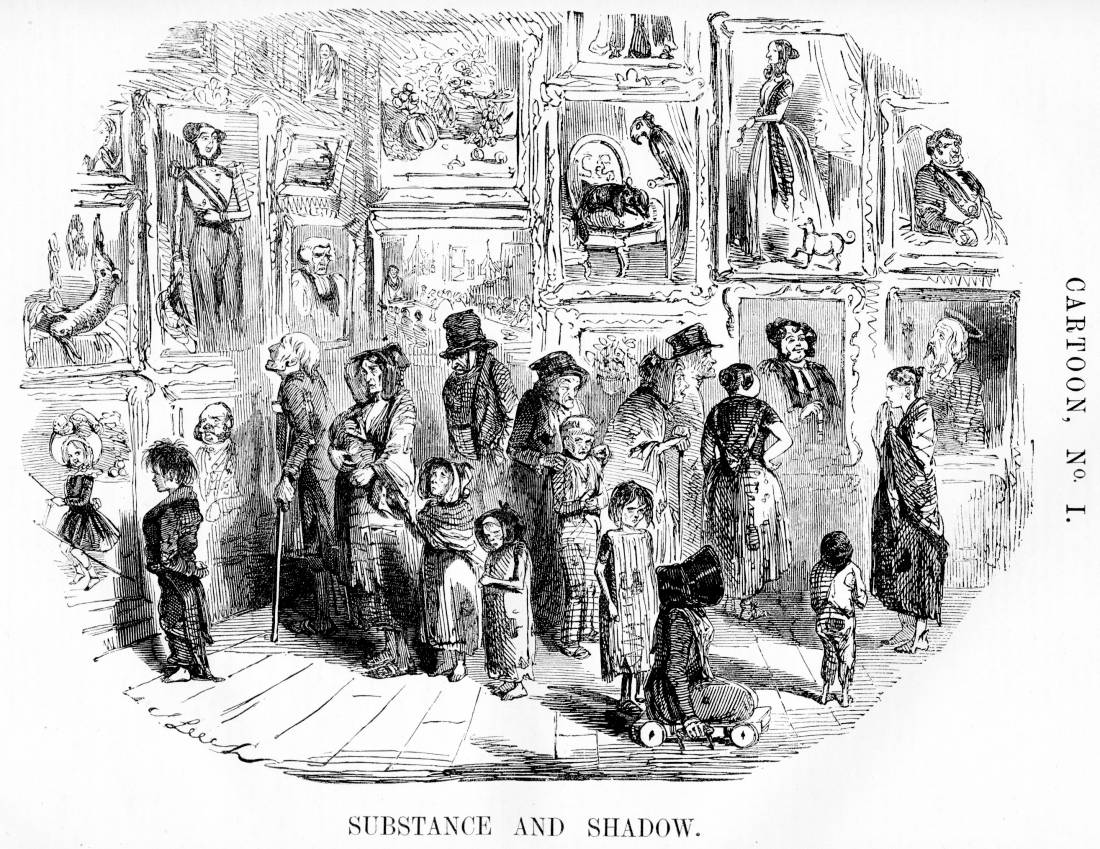

Leech's use of embedded paintings in Substance and Shadow (1843)

Perhaps the finest example of the ironic use of embedded images is John Leech's Punch cartoon Substance and Shadow (15 July 1843), in which the illustrator surrealistically places a crowd of street children in a picture-gallery. Basing his inset paintings upon actual pictures that were exhibited at London's Royal Academy earlier in 1843, John Leech has omitted serious subjects and shown smaller-scale paintings than were actually allowed by the rules of competition: "no less than ten and no more than fifteen feet in their longest dimension," and the figures life-sized. The savage satire involves the halt, the lame, and the young uncomprehendingly confronting establishmentarian images that have little or no meaning for them.

The artist's focal character is the urchin in the cast-off, oversized adult cast-off coat (left of centre) who is curiously examining a portrait of an aristocratic boy of about his own age — the "shadow" of the poor boy's "substance." While the urchin is barefoot, the foppish aristocrat rides a hobbyhorse; while the effeminate boy in the portrait wears a large, eighteenth-century hat with a decorative plume. However, all of the embedded images underscore the social gulf between the poverty-stricken consumers of the exhibit and the upper-class men, women, and children who inhabit the canvasses: judges and attorneys, military commanders, elegantly dressed women accompanied by their lapdogs, exotic birds, and floral arrangements. None of these scenes, however, constitutes a biblical or literary allusion since none of them require special knowledge in order to be assessed against a text.

The New Men of the Sixties

Two of George DuMaurier’s illustrations. Left: "In the Writing of the Composer," Observed Lord Mountclere with Interest, for Hardy's The Hand of Ethelberta (1876). Right: The Doctor preferred to be absorbed in the song in Carita (1876) by Margaret Oliphant

The New Men of the Sixties, including George Du Maurier, Fred Walker, and Fred Barnard, continued the practice of embedding posters, engravings, and paintings in their book illustrations, although with neither the frequency nor the editorial intention of earlier illustrators. These realistic, composite woodblock engravings of the sixties onward markedly differ from those of Phiz, Cruikshank, and Leech by emphasizing the literal, descriptive effects of embedded material rather than any symbolic meaning. For most of the later Victorian illustrators, paintings in parlour scenes serve as mere decoration; they offer little or no editorial comment, and are often generalised portraits and landscapes — rarely is painting recognizable, often because only part of it appears in the picture space.

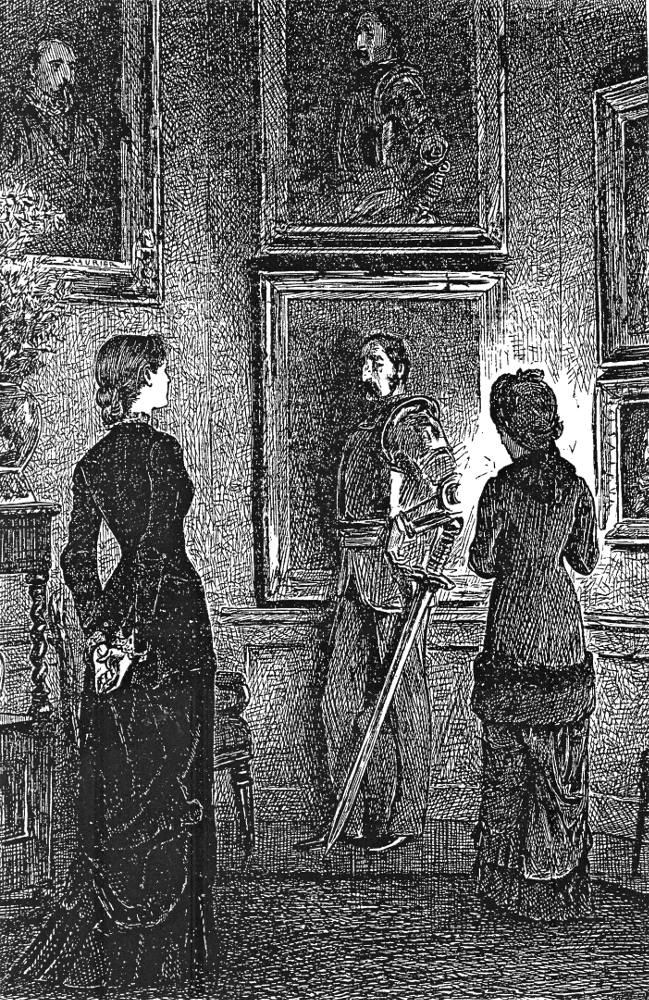

A few examples drawn from the works of the leading realists in illustration underscore their use of paintings primarily as decoration. In addition to these generalised paintings in the background Du Maurier places a manuscript on the piano in his 1876 illustration for Thomas Hardy’s The Hand of Ethelberta (see above) — but the viewer sees only the back of the musical score.This artist's most telling use of embedded images is attributable to Hardy himself in the picture-gallery scene in A Laodicean, when Sir William De Stancy invokes an ancestral portrait to assert his legitimate claim to the title, actually stepping into the oil-painting in full armour in "Is The Resemblance Strong?" (1880). In other words, unless the author specifies a particular meaning or significance for the embedded picture, Du Maurier uses embedded pictures merely to create realistic settings, rather than to comment on the represented action.

Du Maurier's illustration "Is The Resemblance Strong?" in Hardy's A Laodicean (1880): see inset panel for detail of De Stancey standing in the ancestral portrait.

As a detailed analysis of this illustration makes clear, in the picture gallery scene Du Maurier clarifies Hardy's text by showing how De Stancy walks into the frame beneath the portrait of the ancestor he so closely resembles, rendering the resemblance obvious. Moreover, he describes the other De Stancey portraits on the wall, implying a long and distinguished lineage for the middle-aged army officer who hopes to marry the young railway heiress. On the other hand, in the scene in the music room, Du Maurier does nothing to describe the nature of the hand-written sheet-music, although by its position on the piano he does imply that it has recently been played — presumably by his interlocutor, Ethelberta. Only the aged roué sees the music, so that the reader must assess the music from his visual reaction (mild curiosity) and textual comments about it. Du Maurier has so generalised the other embedded images in the music room, the three oil paintings on the walls, that the reader can barely discern whether these are landscapes, cityscapes, picturesque ruins, or seascapes; rather, the frames serve merely to imply the sophisticated taste of the family into which Ethelberta has married. The illustrator furthers this impression by describing the beautifully turned and substantial legs of the grand piano, whose exquisite detailing (the ornamental wing and the harp-style peddle-rest beneath) complements the impeccably dressed peer.

Barnard's illustration "Dead, Mr. Peggotty?" I hinted, after a respectful pause. "Drowndead." in Dickens's David Copperfield (1872).

Barnard, on the other, although thoroughly imbued with the Cruikshank-Phiz technique of placing well-known pictures within the frame, offers a few instances of pictures-within-pictures.A prime example of the functional use of embedded material to comment on the circumstances realised in the illustration is "'Oh Chiv, Chiv,' murmured Mr. Tigg, 'You have a nobly independent nature, Chiv'" in the Household Edition of Martin Chuzzlewit (1872).The pugilistic contest in the picture on the wall about the drunken Chiv suggests the masculine and sporting nature of the establishment, while the poster advertising passage to London foreshadows the next movement of the story, when young Martin, Mark Tapley, Montague Tigg, and Tom Pinch all make their way from Wiltshire to the metropolis. The architectural plans upon which Martin is working in "You're a pair of Whittingtons, gents, without the cat; . . . My name is Tigg; how do you do?", like the other plans in rolls lying against the work-table, are a reasonable extension of Dickens's text concerning Martin's apprenticeship to Seth Pecksniff. In David Copperfield the interiors are full of incidental pictures, some such as the schooner in the Peggottys' parlour in "Dead, Mr. Peggotty?" I hinted, after a respectful pause. "Drowndead" and the map of the south of England and the Channel in Headmaster Creakle's office in "He knows me, and I know him. Do you know me? Hey?" said Mr. Creakle, pinching my ear with ferocious playfulness, making complete sense, but not possessing the additional meanings such images have in the work of the earlier, caricatural illustrators.

Fred Walker's self-satire The Temptation of St. Anthony Walker (1873).

An interesting exception to the general tendency not to embed specific works of art in later Victorian illustrations is Fred Walker's satirical reference to the life of St. Anthony in The Temptation of St. Anthony Walker (September 1873). Although not classiucally trained, Walker evokes a number of Renaissance versions of the saint's legend — Lucas Cranach's woodcut (1506); Bortolomeo Montagna's painting (1510); Grunewald's Isenheim Altarpiece (1515); Hieronymus Bosch's celebrated tryptych (1550); Paolo Veronese's painting (1552); and Lelio Orsi's baroque treatment (1570) — his immediate reference was probably Jean François Millet's 1846 oil on canvas painting, which brought the artist public acclaim and the Légion d'honneur in 1867 when shown in Paris at the Great Exhibition.

A Late Example of a Picture-within-a-Picture: Furniss's Frontispiece for Oliver Twist (1910)

"Are you fond of pictures, dear?" inquired the old lady, seeing that Oliver had fixed his eyes, most intently, on a portrait which hung against the wall; just opposite his chair.

"I don't quite know, ma'am," said Oliver, without taking his eyes from the canvas; "I have seen so few that I hardly know. What a beautiful, mild face that lady's is!" [Chapter 12]

Oliver and His Mother's Portrait, Furniss's frontispiece for Dickens's Oliver Twist (1910).

A late Victorian example of an embedded painting appears in Harry Furniss's realisation of a textual moment in Oliver Twist when Oliver, whom the benevolent Mr. Brownlow has rescued from London's mean streets, falls asleep under the oil portrait of a beautiful young woman in Regency dress — a young woman who, Brownlow notes, bears an uncanny resemblance to the waif. Thus, since the novelist uses the painting within the illustration to prepare the reader for Oliver's recovering his past and his rightful identity, Furniss uses the moment realised twelve chapters after the death of Agnes to establish the keynote for the novel. The inset image of the young woman, Agnes Grey, thus represents the embedded story of the Parish boy and his mother that Dickens establishes at the beginning of the novel, but does not complete until much later. However, the embedded portrait functions very differently from the earlier examples drawn from Phiz and Cruikshank because is not an easily understood cultural icon serving as a commentary for the larger picture; rather, it derives its full meaning from within the text itself at a much later point in the story.

Furniss's 1910 frontispiece also constitutes a visual allusion to the original series of Cruikshank illustrations, which climaxes with Oliver and his aunt contemplating an inset image of Agnes's name in The Church Plate, the final illustration, originally in Part 24, April 1839.

Related Materials

- Chapter 4, Part IV. Word and Image — Problems of Interpretation by George P. Landow (1980)

- The Influence of William Hogarth on Pre-Raphaelite Integrated Symbolism

- ["At Rest (Nell dead)"] by George Cattermole

- Maclise's The Play Scene in Hamlet

- Jack Sheppard exhibits a vindictive character (April 1839)

Bibliography

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Jack Sheppard. A Romance. With 28 illustrations by George Cruikshank. In three volumes. London: Richard Bentley, 1839.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Miser's Daughter. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London, Glasgow, and New York: Routledge, 1892.

Burton, Anthony. “[Review of] John Harvey’s Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators.” Dickensian 67 (1971): 109.

Dickens, Charles. David Copperfield. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ("Phiz"). The Illustrated Library Edition. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1858.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. Illustrated by George Cruikshank. London: Bradbury and Evans; Chapman and Hall, 1846.

Furniss, Harry. "Oliver and His Mother's Portrait." The first of thirty-four illustrations for The Adventures of Oliver Twist in Oliver Twist and A Child's History of England. Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 3, facing the title-page.

Harvey, John. Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators. London: Sidgwick and Jackson, 1970.

Lever, Charles. Barrington. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Chapman and Hall, 1863.

Meisel, Martin. Chapter 13, "Novels in Epitome." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989. Pp. 247-282.

Steig, Michael. "Chapter 1: Dickens and Browne: Illustration, Collaboration, and Iconography." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London; Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp.1-23.

Last modified 13 December 2024