avvies built canals, railways, dams and then pipe tracks, the big

nineteenth century sea-port docks, and the Manchester Ship Canal.

avvies built canals, railways, dams and then pipe tracks, the big

nineteenth century sea-port docks, and the Manchester Ship Canal.

Navvying began suddenly in 1763 in the Bridgewater Canal: it ended around 1943, after a twenty-year fade-out. Along with the rest of Britain there was a kind of kink in the navvy's history in the 1870s when things began changing, generally for the better.

At first they were just skilled earth shifters digging canals at prodigious speed. Later they were skilled in tunnelling, mining, timbering — skilled enough to set up as one-man contractors employing local unskilled labourers to shift their muck. You could set a gang of prime navvies down in an untouched valley, they said of themselves, and they'd build you a dam without aid of an engineer. At times they slotted into the pay scales at twice a common labourer's wages, though they never equalled apprenticed craftsmen like masons.

It is easy for the urbanised and pensionable to romanticise them. They seem free, fearless above the humdrum conventions of shopkeepers, clerks, factory workers, vicars, and the legally wed. Perhaps we glamorise cowboys, blue-water sailors and the hell-bent navvy for the same reasons. In reality, isolation was the biggest thing in a navvy's life. They were perpetual outsiders: a people apart. Sub-working class. Sub-the-bottommost-heap of English working society. Sub-all, almost.

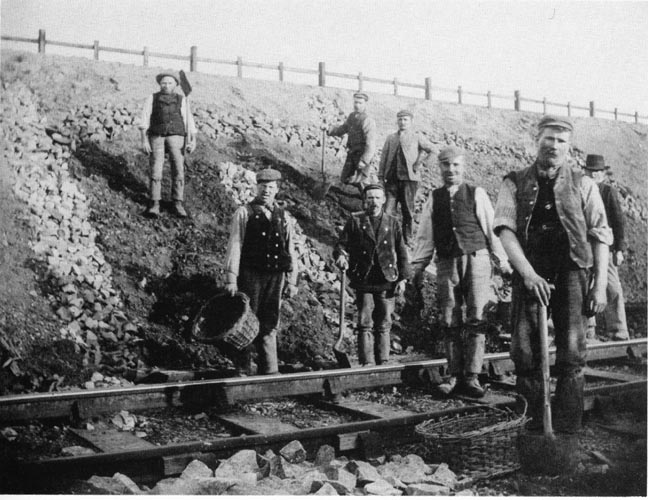

Left: Railway Navvies. Right: Navvies, 1890s

Click on thumbnails for larger images.

The navvy never called a spade a spade, always a bloody shovel. Everything he shovelled he called muck. Earth, blasted rock, clay, all were generically and indiscriminately muck. With the muck he created new landscapes and changed old societies. It was mass transformation by muscle and shovel.

To do so navvies worked in geographical and social isolation; crude, muck-caked men on a helix spiralling down from prejudice [4/5] to more isolation, isolation to more prejudice. Eighty per cent were English, most of their work was in England, yet they lived like aliens in their own country, often outside its laws, usually outside its national sense of community. They were their own country's non-belongers. They belonged to themselves only tenuously. Mostly they lived apart in navvy settlements. New habits of life, thought, dress, speech, and a tightening of the ring against outsiders came out of their isolation. Their own countrymen were terrified of them, and despised them. Heavy drinking was normal, death by alcohol common. Drink was a common cause of riot, along with an unhesitating hatred for their own Irish minority. Their accident and death rates were higher than any other group in Britain, including colliers, including soldiers fighting nineteenth-century wars. Often they were nameless, known to each other only at second-hand by nickname. They were a homeless, wandering itinerant people belonging nowhere except to the island as a whole.

They survived the Great War as a separate community, but not for long. Nawying was killed by a lack of large scale public works (worsened by the Slump), by bureaucracy and by the petrol engine. Probably in that order. By the mid-1950s they were quietly ending as a recognisable separate community. Individuals did live and work on. Their descendants still do (at their height, just before the Great War, there may have been as many as a hundred and seventy thousand of them).

In one way the navvy's is a story of a long taming as things got better for them (mainly from bestial to bad), chiefly because the country changed (from bad to better), but also because of a few individuals, events, and institutions.

To begin with there was the Select Parliamentary Committee which sat for a few days in the summer of 1846, alternately dismayed and appalled by the way the navvy lived and behaved.1 The Committee got none of the things it asked for, though perhaps that mattered less than the fact that Parliament had taken the trouble to be shocked.[5/6]

Mrs. Elizabeth Garnett.

In the 1850s Katie Marsh, a vicar's daughter, wrote a book about navvies which was very widely read and very influential in changing people's perceptions. From the late 1870s they had their own Mission to tame and christianise them. It, too, was dominated by a vicar's daughter (and a vicar's widow) — Mrs Elizabeth Garnett. The Mission reached the heathen navvy through resident missionaries and its quarterly magazine, the Navvies' Letter. From the 1890s they had their own trade union, which they ignored in vast numbers. After 1906 they had an MP in the House of Commons: John Ward, one of the Union's founders. It all helped, but nothing ended their isolation. Navvies remained a people apart.

'In the making of the canals, it is the general custom to employ gangs of hands who travel from one work to another and do nothing else,' Peter Lecount, a railway engineer, said of them in 1831. 'These banditti, known in some parts of England by the name of "Navies" or "Navigators", and in others that of "Bankers", are generally the terror of the surrounding country: they are as complete a class by themselves as the Gipsies. Possessed of all the daring recklessness of the Smuggler, without any of his redeeming qualities, their ferocious behaviour can only be equalled by the brutality of their language. It may be truly said, their hand is against every man, and before they have been long located, every man's hand is against them.'

'The women shun us as lepers are shunned,' Patrick MacGill, a navvy, said in the 1900s. 'The brainless girl who works with a hoe in a turnip field will have nothing to do with a tramp navvy. The children hide behind their mothers' petticoats when they see us coming, frightened to death of the awful navvy man who carries away naughty children, and never lets them back to their mothers again.'

What they said about navvies was often true (true perhaps more often than not) yet it was also often exaggerated and sometimes undeserved. In the early 1840s the Bristol and Exeter railway was being laid along the Culm valley below the fat red hills of Devon. At one point the river swirls around Killerton Clump, a remnant of a volcanic cone. Tucked into one side is Killerton House, then home [6/7] to Sir Thomas Acland who spent his life landscaping his estate. Around 1845, three hundred navvies intruded unexpectedly into this deeply rural place ahead of their materials. Terror stained the entire countryside. Landowners in panic barred their windows, armed their servants, prepared to repel, or kill. All except Sir Thomas, the tenth baronet. He hired them to make a road from his house to the highway, the sunken Devon lane about a quarter of a mile away. When they tapped into a spring, he hired them to pipe water to the house.

Eighty years later, in 1924, navvies again worked in Killerton Park, laying a pipe track. The Great War was safely over. Killerton Clump still overlooked the long views of Devon: woods behind hills, hills beyond woods, all misty with damp and distance. Sir Francis Acland, fourteenth baronet, now owned Killerton and in 1924 his ten-year old daughter Ellen was killed on her bicycle outside the park gates.

'I am a perfect stranger,' one of the navvies wrote to her parents, 'but I shall never forget the bright little angel who used to greet me with a smiling face and a cheery good morning when I chanced to meet her while working the pipe track through Killerton Park. I feel as though I would have given my useless rough old life to have saved that little maid, and may God comfort you. Sir and Madam, for this great trial he has put upon you.'

There was a place coming up out of the bottom and a little boy got struck and killed by one of these carts off the works. His little sister ran indoors shouting, 'Look at Tommy — his head's all jam.' She didn't understand, you see.

They think rough fellers like me have got no heart, but I could see that little boy for years after.

Sources

MacGill spoke of women shunning navvies like lepers in Children of the Dead End. The Aclands are from Quarterly Letter to Men on Public Works April 1924.

Last modified 19 April 2006