[Photographs and formatting by the author, but the copyright of the photographs has been assigned to Manchester City Council; they should not be reproduced without the Council's permission. Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Main entrance vestibule

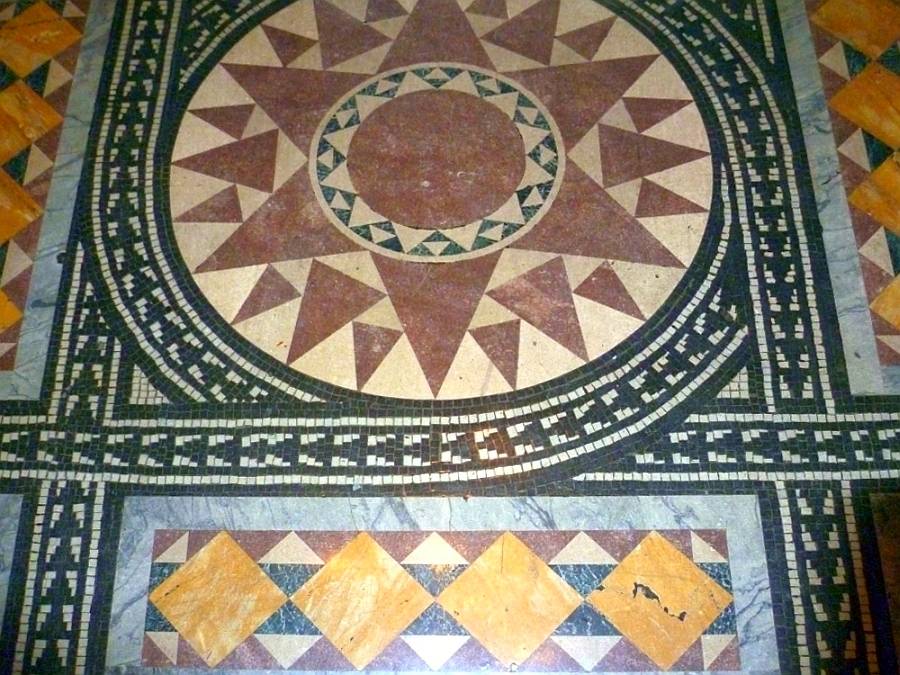

Right to left: (a) The rib-vaulting of the vestibule. The ceiling is decorated with a mosaic of gold and black foliage, with a painted heraldic roundel in the middle. Interestingly, this is not the city's own coat of arms but the British one, with a lion and a unicorn on either side (Manchester has a stag rather than a unicorn), and sports the British motto, "Dieu et Mon Droit" rather than Manchester's "Concilio et Labore." (b) Glimpses into the Sculpture Gallery. Facing each other on opposite sides of the vestibule are the seated statues of the two important scientists with strong local connections, John Dalton, by Sir Francis Chantrey (1837), and J. P. Joule, by Alfred Gilbert (1893). The recess behind Joule on the right has a triple-arched unglazed window, complete with trefoils, looking on to the adjacent Sculpture Gallery. (c) Floor tiling of coloured marble, with a wheel pattern in the middle. Both outside and in, Manchester Town Hall is a prime example of Ruskinian Gothic. While the exterior shows its debt to Ruskin in its "freedom of asymmetry ... emphasis on massiveness and vigour of expression," its interior, which is "stylistically consistent" with it, shows Ruskin's influence most obviously in its vivid polychromy (Archer 75-77). For this reason amongst others, it is, as the listing text says, a "[b]uilding of major importance."

Ground floor: arches and vistas

Views inside the town hall. These make an immediate impact, thanks to the glimpses even from the vestibule. In general, the views through beautifully carved arches and equally elegantly finished polished granite columns are breathtaking. John Archer rightly draws attention to Waterhouse's effective "linking of spaces through open arcading, which gives unexpected views either into individual spaces or across a whole sequence of them," and praises "the command of plan, space and structure that is Waterhouse's hallmark" (76). These are the qualities that probably contribute most to the building's success. Notice the narrower stone banding above the capitals, the mosaic flooring, and how the staircases are used to add drama to the interior. Among various symbolic touches, the flowers in the floor mosaic are cotton flowers (see Cunningham 184), which precede the cotton bolls, and symbolise the main source of Manchester's wealth.

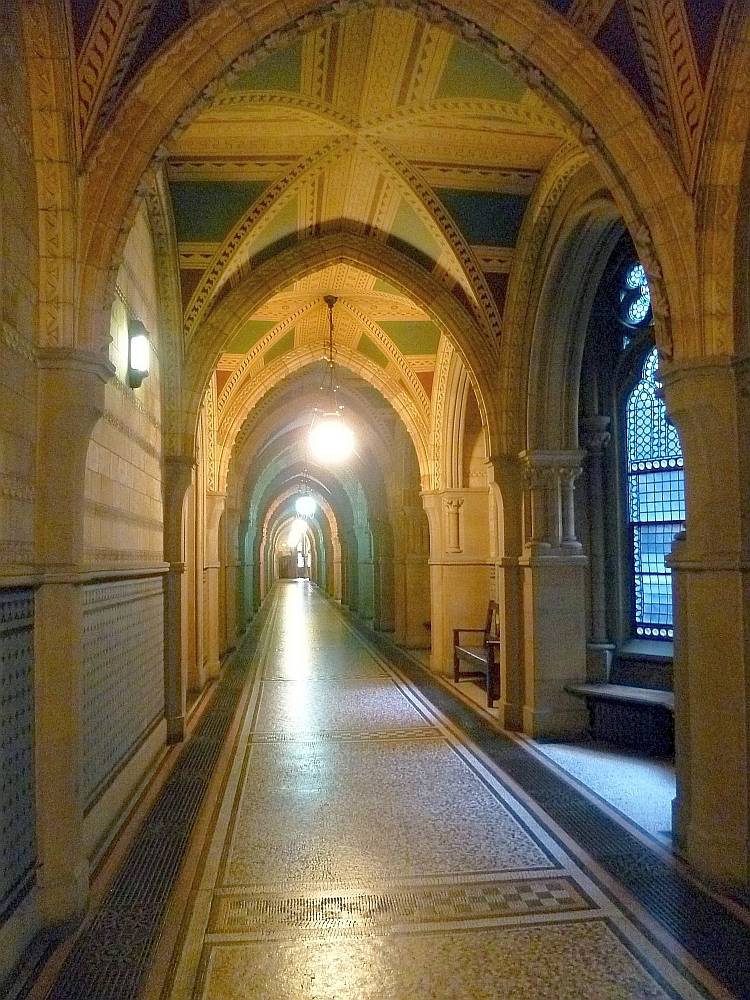

Ground floor: side corridor

A side corridor, with windowed recesses. The corridors, like those on the first floor, are "[r]ib-vaulted polychromatically in stone in bands of two contrasting colours, buff and blue-grey, ... lined in terracotta in matching colours above a richly patterned, tiled dado" (Archer 79). The ceiling is particularly impressive because of its colour and stencilling, and the tall windows throughout are another decorative as well as practical feature, not filled with rich stained glass that would have reduced the light, but only partially patterned in subtle shades of blue, pink, violet, red and green — often with a floral motif. Archer not only notes "the manipulation of axes and cross-axes" seen elsewhere (76), but points out usefully that "[a]though often overlooked, decoratively, the circulation areas are as important as any individual room" (80).

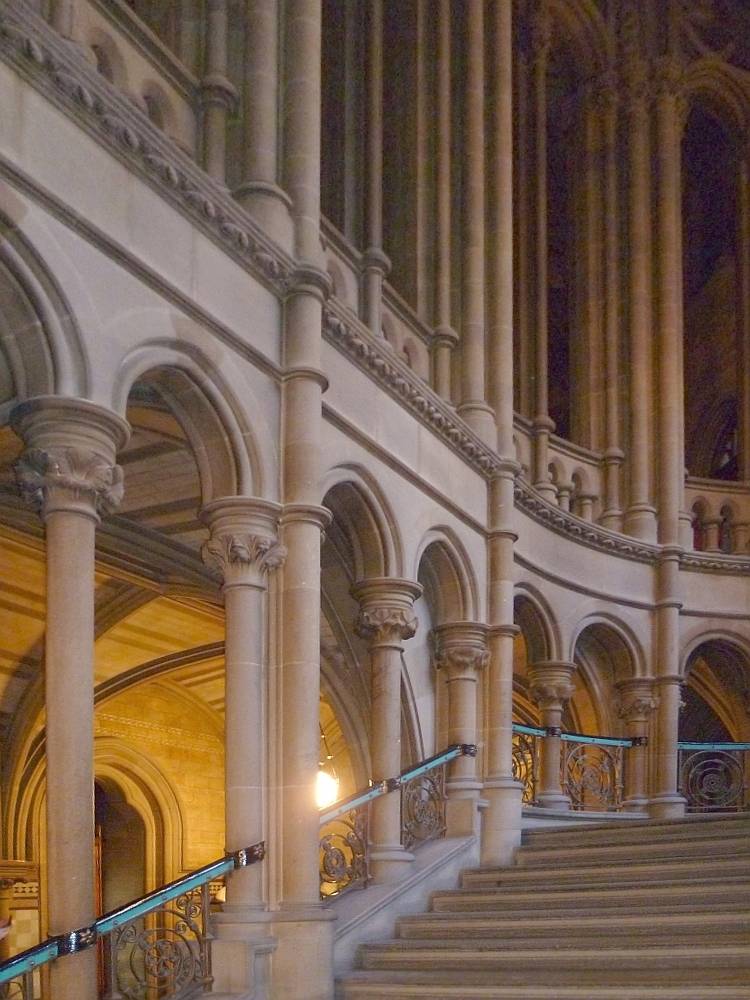

Stairways

Left to right: (a) One of three smaller staircases spiralling up to the first floor. In all, there are seven staircases to the first floor. Even these less showy ones are "enriched [respectively] with treads and paired columns of English, Irish and Scottish polished granite" (Cunningham 184). Running through the curving banister rails are the gas-pipes for the lighting ("A History of Manchester Town Hall"). (b) One of the pair of grand staircases that lead up by more graduated steps from the lower foyer to the upper one. These impressive staircases are "each enclosed within a vaulted semicircular apse, and each is flanked by a range of tall windows lit from a courtyard" (Archer 79). On this, the more southerly and principal staircase, visitors are cheered on their way up by William Theed's statue of John Bright. (c) Impressive carving on one side of the other grand stairwell. (d) Open arcading lower down on the same stairwell.

On the first floor is an arcaded landing with an unusual glazed wagon-roof serving as a long skylight, and inscribed with the names of past dignitaries, as well as flowers (including cotton-flowers) and leaves. Brightness is added too by the white mosaic floor-tiling here, this time patterned with yellow and black striped bees, a symbol of industry — as featured on Manchester's heraldry. This gives onto the official staterooms, the most splendid of which is the Great Hall with its panelled ceiling painted with the heraldry of Manchester's trading partners. This room is home to the town hall's single most important decorative element — Ford Madox Brown's celebrated and rather controversial series of twelve murals evoking Manchester's history, from "The Romans Building the Fort of Mancenion AD 60" to "Dalton collecting Marsh-fire Gas" (the basic idea was similar to that of William Bell Scott's murals at Wallington, depicting Newcastle's history; but the treatment is far less earnest.). The Banqueting Hall and Council Chamber are almost as grand as the Great Hall itself. Through all this splendour, the building proclaims and indeed flaunts the city's pride in its achievements and standing.

Details

Left to right: (a) Carving on the capitals. Farmer & Brindley were responsible for the carving on the exterior of the town hall (Archer 74); presumably they worked on the inside as well. But it is impossible to ascribe carving to individuals: "a huge number of stonemasons were employed ... for the last twelve months over 700 alone" (Parkinson-Bailey 112). (b) Stone-carving on an arch. This features various kinds of leaves, and, rather whimsically but very much in the High Victorian style, a cat and an owl. William Burges would no doubt have approved. (c) Wall tiling. This varies in pattern and is part of the final effect.

As Archer says, "Waterhouse's hand can be seen everywhere in the building" (83). He even designed the furniture, the dinner service and so on. As a whole, considering the scale and complexity of the project, Manchester Town Hall is a remarkable piece of work, the "last great Gothic building in the country" (Parkinson-Bailey 109), yet one that has not only gas pipes running through the banisters but sophisticated water, heating and sewerage systems, and telegraphic links between the main offices. Just as it reflects the city's finest hour, so it tells of an architect at the very height of his powers.

Related Material

- Manchester Town Hall: Artistic Decoration

- Manchester Town Hall (exterior view)

- Manchester Town Hall (some exterior details)

- Ford Madox Brown's murals in the Great Hall

Bibliography

Archer, John H. G. "Manchester Town Hall." In Manchester, by Clare Hartwell. Pevsner Architectural Guides. London: Penguin, 2001. 71-84. Print.

Cunningham, Colin. Victorian and Edwardian Town Halls. London: Routledge, 1981. Print.

"A History of Manchester Town Hall." (Click on the link near the end to take panoramic virtual tours of the first floor rooms.) Manchester City Council. Web. 15 April 2012.

Parkinson-Bailey, John J. Manchester: An Architectural History. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. Print.

"Town Hall, Manchester." British Listed Buildings. Web. 15 April 2012.

Last modified 20 April 2012