Images of these murals have been downloaded from "Ford Madox Brown Murals" and are reproduced here by kind permission of Manchester City Council. Click on the images for bigger pictures, and individual commentaries on them. The opening image showing a few of the works in situ is by Tom Page, and has been taken, with thanks, from Wikimedia Commons, under the Creative Commons license. It has been slightly modified by the present author. Click on this too for a bigger picture.

Introduction

The Great Hall, the most richly decorated room in Manchester Town Hall, designed by Alfred Waterhouse (1830-1905), and built from 1867-1877, a symbol and proclamation of Manchester's civic pride.

In 1878, after protracted debate, the Decorations and Furnishings Sub-Committee of Manchester Town Hall finally commissioned Ford Madox Brown and his friend Frederic Shields, another artist associated with the Pre-Raphaelites, to paint six murals each for the new building's Great Hall. The murals were the idea of the architect himself, and were intended to illustrate the city's proud history — or, in some cases, to endow the city with such a history. Shields never started his part of the project, and formally withdrew from it in May 1881. In January 1884, at the urging of the architect himself, a new contract was negotiated, and Brown was finally and formally asked to complete all twelve panels himself (see Treuherz 64). Because of Waterhouse's involvement and support, the work when completed would be seen as "a model for collaboration between artist and architect in the decoration of public buildings" (Treuherz 20).

The project was significant in other ways too. Its scale would make it an outstanding example both of Victorian narrative painting, and of the fresco revival of the nineteenth century. This revival had started with the decoration of the garden pavilion in the grounds of Buckingham Palace (mentioned in older accounts of the Palace, but since demolished), and been well and truly launched by the grand historical frescos by William Dyce and others in the new Palace of Westminster. Echoing such projects, the town hall murals were to put the finishing touch to Manchester's new civic showpiece. They were to run down each long side of the rectangular hall, under its high windows and above its oak-panelled lower wall, six on each side. It was a mammoth undertaking for the artist, and, like previous undertakings of this kind (including the one at the Palace of Westminster), fraught with problems.

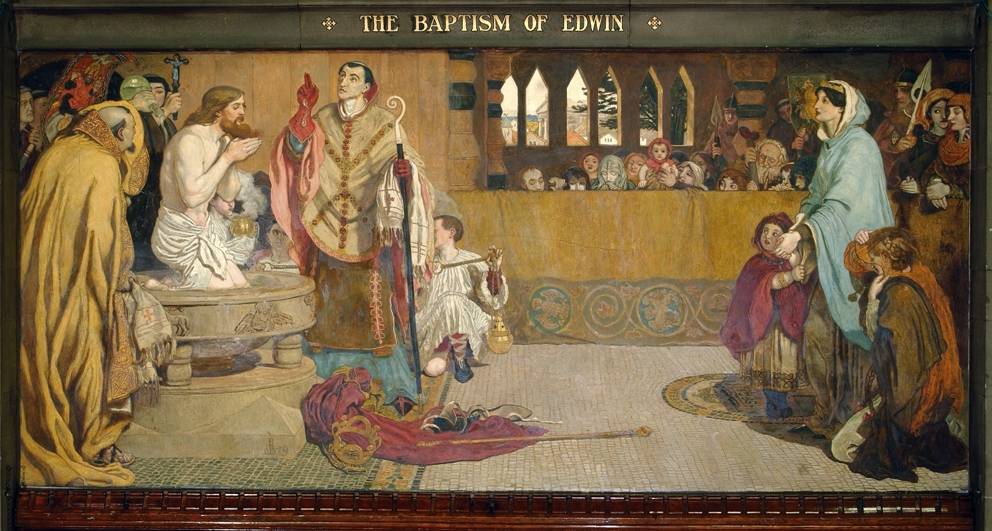

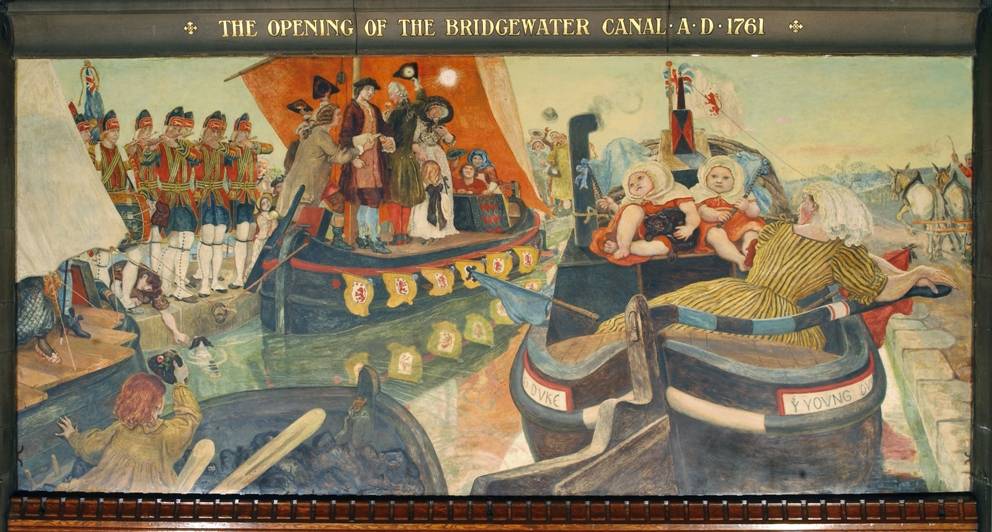

Not the least of these problems was the choice of subjects. Manchester was a radical city, and Brown had every sympathy with that. His grandson and biographer, Ford Madox Ford, would describe him in his later years as "a Socialist of an extreme type," always sympathetic to the "humble and meek" (401, 400). His emphasis would be on the participation of ordinary folk in the city's history. Not surprisingly, then, one of the dramatic episodes he and Shields originally wanted to record was the Peterloo Massacre, when popular demand for reform provoked but was not, in the long term, quashed by a violent response. Indeed, they wanted this to be the climax of the series. The final subject in their original proposal was: "12. The Peterloo meeting [which led to Reform, which led to Free Trade, without which no steam-power could have availed] at Manchester" (qtd. in Ford 332). But this was one step too far for the town hall's committee, and the tamer, festive occasion of the Opening of the Bridgewater Canal was added to the list as an alternative subject. It was at least specific to Manchester and highly relevant to its progress, unlike one or two of the others — the second in the sequence, The Baptism of Edwin, celebrates an event that, for all its wider significance, took place in York. Unfortunately, though, the carnivalesque scene of the canal's inauguration would be poorly received by the late Victorians, partly because of the prominence given to a bargee's wife and babies. It would be entirely natural for Brown to show pomp and circumstance being invaded in this way, but the outcry against it would distress him: "Perhaps the most cruel of all his many causes for sorrow was the opprobrium with which the panel of the Bridgewater Canal was received on its instalment at Manchester" (Ford 394).

Problems of selection and reception aside, the process of painting the twelve large murals was in itself a trying one. Brown started work on the cartoon for The Baptism of Edwin in the July of 1878, moving to Manchester for several months in the following year, and spending the best part of eight years there before finally moving back to London in December 1887 (see Treuherz 64-65). The Baptism was finished first, in 1879, and Bradshaw's Defence of Manchester last, in 1893, several years after he had returned to London. In all, he spent about fourteen years on the project. The first seven episodes were painted in situ, using a technique learnt from Thomas Gambier Parry (1816-1888), which involved preparing the surface with whiting and white lead, and heating a mixture of "appropriate pigments, oils and resin" as the medium (see Lambourne 59). Although Waterhouse had done all he could to ensure success, it was still challenging, as Brown quickly realised when painting his very first one, The Baptism of Edwin:

There are difficulties with the work itself, however, that one could not count on such as shadows cast at certain hours by the projecting piers on either side, and sunshine. These, of course, I manage to counteract, but the result is that time is wasted and the difficulty of obtaining the desired result increased. I have almost finished four figures of monks or priests those to one's left but I consider I am much behind. The heating apparatus is perfect. The daylight on fine days is sufficient, but without the gas [lighting] on many days I could do nothing. (qtd. in Ford 336)

Brown complained that the method too was irksome: "I am not quite so satisfied as I was with the Gambier Parry process. I find it keeps on drying and getting paler for three or four weeks, which makes it difficult to know what one's work will look like, so that I may possibly do the next on water-glass and have the wall roughened up. Things are looking awfully down with me, but I must conclude" (qtd. in Ford 337).

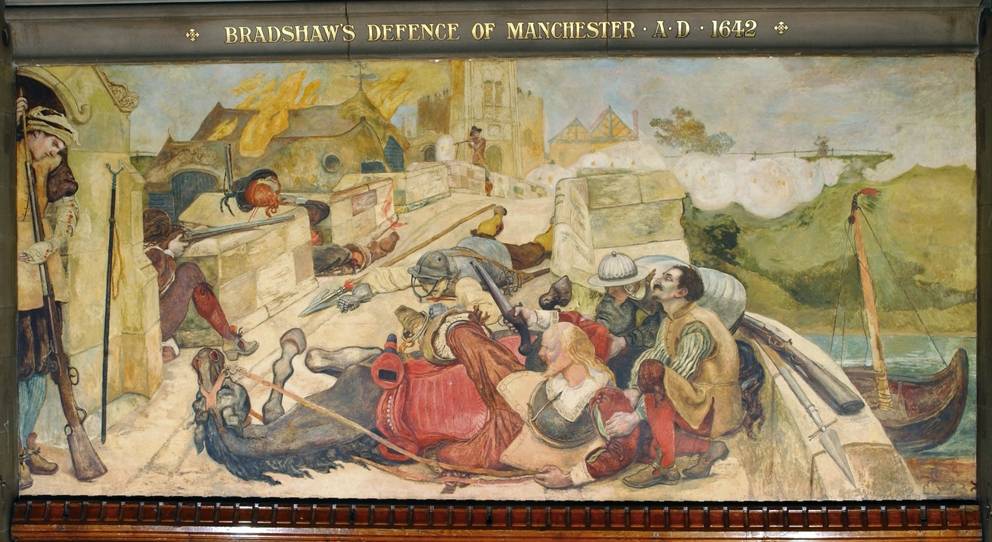

Admittedly, he hardly made things easier for himself, as stories about his efforts at veracity carefully illustrate: for example, in true Pre-Raphaelite fashion, he is said to have gone up to the top of the town hall's very high tower in order to see the bugle (for the Roman picture) without the reflection from the gas lighting inside the Great Hall (see Treuherz 284-85). Not surprisingly, then, especially in view of the cold winter of 1885, the last five works were painted in his studio, "one in spirit fresco and the rest in oils" on canvas (Treuherz 283), which was then fixed to the wall by adhesive, in a process called marouflage. Despite this change, the paintings are of uniform size, measuring 10.6' x 4.9' (or 3.2m. x 1.45m, according to Archer 81). This was Brown's last big commission: he died shortly after completing it, in 1893. In the long run, the murals may have established the city fathers as "admired leaders of public art patronage" (Balshaw 6), but Brown's death was perhaps hastened if not actually caused by criticisms of them, and even the possibility that they might be removed (see Paxman 52). Fortunately, as Rossetti had prophesied earlier on, the "Manchesterians" decided they had "paid too much to whitewash it again" (qtd. in Ford 345), and the murals are still there to be enjoyed today.

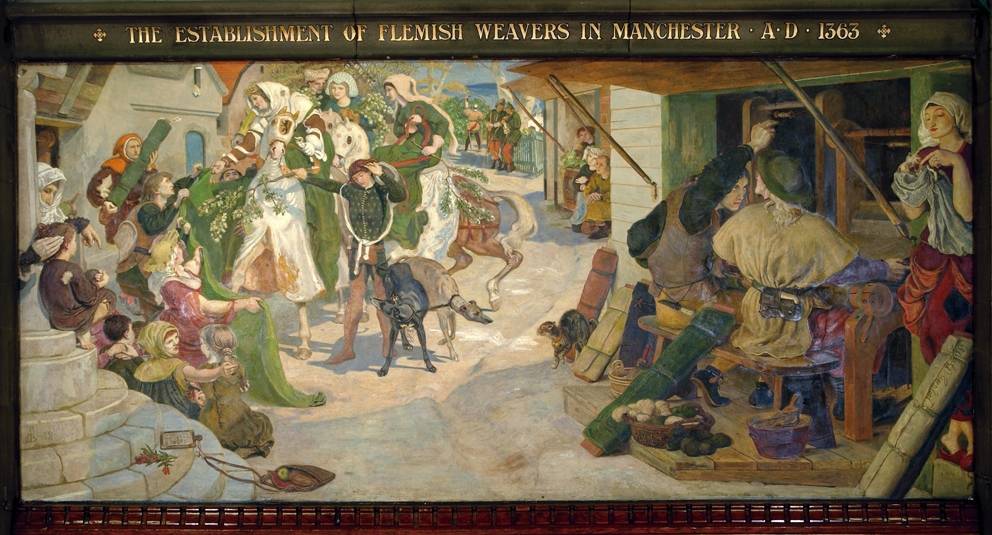

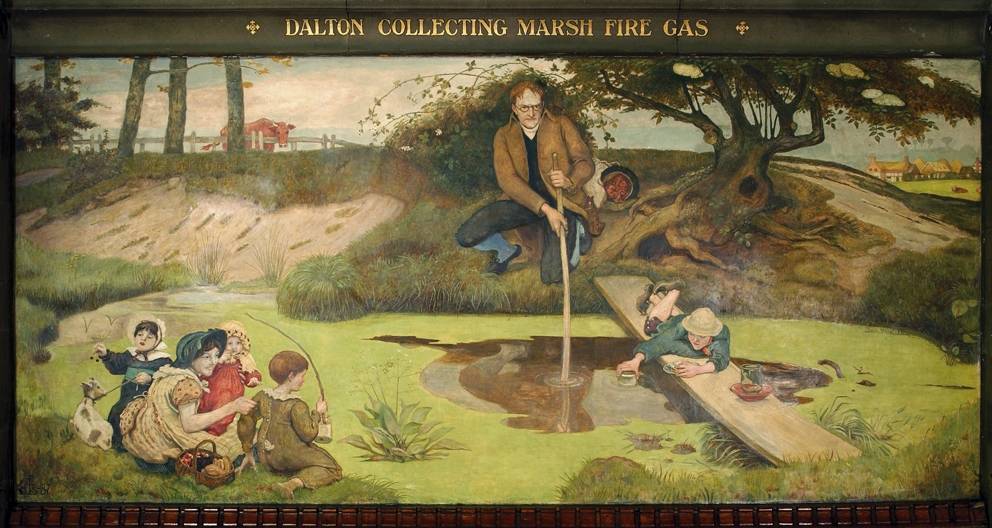

Fortunately, too, Victorian narrative art is better appreciated these days than it was even thirty or forty years ago, partly for its details, which often tell us as much about ourselves as about the past. In Brown's case, we can now revel in the inclusiveness of his vision, his evident and good-humoured delight in the way ordinary life goes on in exceptional circumstances. The young weaver still trying to catch the eye of a pretty girl when the Queen comes by (The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester) or the little boy waiting to fish in the swampy water where a famous scientist is conducting his experiment (Dalton Collecting Marsh-Fire Gas) are not really marginal. They relay the steady beat at the heart of things. As for the art itself, to the extent that this can be separated from the artist's vision, critics are no longer apt to dismiss narrative painting as "not in the top aesthetic flight" (Hadfield 145). Brown's unexpected juxtapositions and disjunctions, exaggerations, dynamism, bold and vibrant colours, certainly do more than justify the higher evaluation now being placed on his work.

Key

The murals are given in the order in which they appear, starting from the left of the Great Hall's entrance, and following on round the room, which has six murals on each side. When not shown in the title above the mural, the date of the historical event celebrated is added in square brackets, except in the case of Dalton's experiment, which cannot be dated precisely. The date of completion is given in round brackets at the end. More information in the individual commentaries when you click on the images.

Left: The Romans Building a Fort at Mancenion. AD 80 (1880). Right: The Baptism of Edwin. [AD 627] (1879).

Left: The Expulsion of the Danes from Manchester. [AD 910] (1881). Right: The Establishment of Flemish Weavers in Manchester. AD 1363 (1882).

Left: The Trial of Wyclif[fe]. [AD 1377] (1886). Right: The Proclamation Regarding Weights and Measures. AD 1556 (1884).

Left: Crabtree Watching the Transit of Venus. AD 1639 (1883). Right: Chetham's Life Dream. AD 1640 (1886).

Left: Bradshaw's Defence of Manchester. AD 1642 (1893). Right: John Kay. Inventor of the Fly Shuttle. AD 1753 (1890).

Left: The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal. AD 1761 (1892). Right: Dalton Collecting Marsh-Fire Gas (1887).

Related Material

Bibliography

Archer, John H. G.. "Manchester Town Hall." Manchester. Pevsner Architectural Guides. London: Penguin, 2001. 71-83. Print.

Balshaw, Maria. Foreword. Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer., by Julian Treuherz, with contributions by Kenneth Bendiner and Angela Thirlwell. London: Philip Wilson, 2011. 6-7. Print.

Ford, Ford Madox (Brown's grandson). Ford Madox Brown: A Record of His Life and Work. London: Longmans, 1896. Internet Archive. Web. 22 April 2012.

Hadfield, John. Every Picture Tells a Story: Images of Victorian Life. London: Herbert Press, 1985. Print.

Lambourne, Lionel. Victorian Painting. London: Phaidon, 1999. Print.

Paxman, Jeremy. The Victorians: Britain through the Paintings of the |Age. London: BBC Books, 2009. Print.

Treuherz, Julian, with contributions by Kenneth Bendiner and Angela Thirlwell. Ford Madox Brown: Pre-Raphaelite Pioneer. London: Philip Wilson, 2011. Print.

Last modified 1 August 2012