The front cover of the pdf version reviewed here shows a detail of Frederic Sandys's Morgan-le-Faye of 1864. [Captions and links added by JB. Click on this and the following images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.]

The first surprise on reading the catalogue of Radical Victorians, which opened in Birmingham in February, and runs until 31 October 2024, was to see that it came out in 2018. It was written to accompany a touring exhibition conceived in association with the American Federation of Arts: it mentions five venues on the other side of the Atlantic between October 2018 and September 2020, but two others were added, and COVID obviously ruined that carefully planned programme, extending the tour there as far as January 2022. (This also means that the book was intended for an American audience, hence the comments on the "color" and "splendor" of the Pre-Raphaelites — although British spellings have been preserved in the quotations from Victorian artists, and Ford Madox Brown's An English Autumn Afternoon was not turned into An English Fall Afternoon).

However, the exhibition was curated by three British specialists. Tim Barringer, now Paul Mellon Professor at Yale University, is well known for his expertise in Victorian paintings, among other subjects. Martin Ellis has been curator of applied art at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery for many years, and his colleague Victoria Osborne specializes in Victorian works on paper. Since one aim was to promote Birmingham's importance abroad, the catalogue quite logically includes several texts about the city which was once "the workshop of the world" before it reinvented itself as a cultural centre.

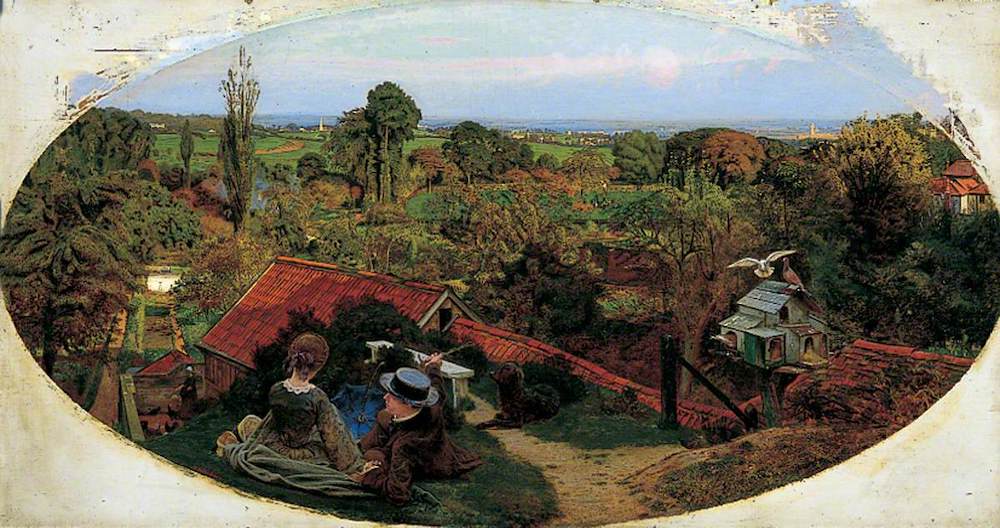

Ford Madox Brown's An English Autumn Afternoon, on display in the exhibition and featured in the book as well, on p. 42.

The four essays in the volume are neatly divided into two more general discussions: the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, by Tim Barringer, and Victorian decorative arts, by Martin Ellis; and two more geographically focused approaches: a brief history of the museum and its collections, by Martin Ellis, and a paper about Edward Burne-Jones and the artists of the Birmingham group. It should be added that some of the individual entries for the works on display were written by Zelina Garland-Rowan.

Reviewing the exhibition for the Victorian Web soon after it opened, Simon Cooke lamented "the thinly written and underwhelming information boards," on which such key notions as "radicals" or "Pre-Raphaelite" were never defined. In his contribution to the catalogue, Tim Barringer seems to have anticipated exactly this reproach. Not only does he brilliantly summarise the history of the Brotherhood, which was founded in a year when Chartism was still very active in Britain (just a few months before the birth of the PRB, Hunt and Millais attended a Chartist meeting on Kennington Common), but he is also careful to explain how the group of young artists could be considered radical. Barringer borrows a definition of the word from no less than Karl Marx ("'To be radical is to grasp the matter by the root,' Karl Marx noted in 1843" [36]) and goes on with a series of subtitles which all include the adjective: "Radical Medievalism", "Radical Brotherhood", "Radical Realism," "Radical Politics," "Radical Faith," "Radical Genderings," "Radical Visions" and "Radical Impact."

Barringer may, however, have been carried away by this enthusiasm, which leads him to formulate some questionable claims. When he writes, for instance, that "Turning his back on a millennium of accumulated artistic tradition of depicting the Holy Family as timeless figures — surely a radical move — Hunt resided in Jerusalem between 1854 and 1856" (44), one might object that this is exactly what Sir David Wilkie, who was far from being a radical, wanted to do when he left England to the East in 1840 — and would have done, thanks to the many sketches he painted on the spot, had he not died on his return voyage the following year. Women artists are currently revalued from the same "radical" perpective, and rightly so, but in the case of Elizabeth Siddal, her "willingness to push harder than her male colleagues against rigid academic norms" (46) may have had more to do with her lack of formal training than with any kind of radicalism — although it does seem that she provided Dante Gabriel with some compositional ideas, as shown in the Rossettis' show at Tate Britain in 2023. And if it sounds quite believable that "Pre-Raphaelitism was a significant precursor to both Symbolism and Surrealism," it might be interesting to know more precisely how "many of the twentieth century's utopian enterprises, […] and even Mahatma Gandhi's political philosophy, also counted Pre-Raphaelite radicalism as part of their inheritance" (50).

In the next section, "Practice and Ideal: Ideas and objects," Martin Ellis turns to "one particular tradition in the history of British decorative art" (53), the creation of unique luxury objects, from A.W.N. Pugin to the Arts and Crafts movement, since one special feature of the exhibition is to include not only paintings, drawings and sculptures, but also stained glass, earthenware, glass and metalwork, jewelry and even dresses.

Left: Exterior of the gallery, seen from an angle. Right: A glimpse of the current exhibition, as shown on the gallery's own website, showing the variety of artwork on display, including stained glass and high fashion: the court dress seen in front here is made of fabric designed by William Morris. The dress-designer, Sarah Fullerton Monteith Young, also supplied dresses for Marion Sambourne and her daughter (see p.198).

Ellis's other contribution to the catalogue, "'By the Gains of Industry we Promote Art': The Birmingham Collection" reminds us that a major objective of the show is to celebrate the wealth of the local collection of Victorian art and design, which is such that it allows for a complete overview of the Pre-Raphaelite movement, from its original founders to its second generation, and even its perpetuators in the early twentieth century.

He retraces the origins of the Museum as a small gallery within the Central Library, and its transformation into a much more ambitious institution including not only an art gallery but also a municipal school of art, thanks to the generous gift of two industrialist brothers, the Tangyes, in 1880. The Museum and Art Gallery opened in 1885, an extension, rendered possible by various donations, was built in 1911, and after World War Two, it was decided that it was time to enrich the collections in order to reflect the city's industrial history and, as a complement to its splendid Pre-Raphaelite holdings, to purchase objects so as to represent "the broader artistic world of the time" (32).

The Municipal School of Art, opened in 1885, the first of its kind in the country.

Victoria Osborne's focus is on a single artist, yet it can hardly be said to be narrower. Burne-Jones was a child of the city (even though he initially wanted to distance himself from polluted, commercial and vulgar Brummagem). Among other things, she shows that, despite his poor opinion of his native place, he could have seen quite a few examples of Pre-Raphaelite arts there, thanks to the efforts of the Birmingham Society of Artists: Millais sent his Ophelia in 1852 and Hunt's Strayed Sheep won the prize for the best painting in 1853, the year when Burne-Jones left for London. When he became the sensation of the exhibition of the first Grosvenor Gallery, in 1877, some of the local reformers tried to reconnect with him, "soliciting his endorsement and support" for their "social and cultural campaign" (76).

When the Museum opened in 1885, it could only boast an "embryonic Pre-Raphaelite collection" (77) – a landscape by John Brett, two unfinished paintings by Rossetti and a sculpture by Alexander Munro – but eleven works by Burne-Jones were added, lent by private collectors (while G.F. Watts loaned a "much larger collection" of his own paintings). A whole series of stained-glass windows were then commissioned from Morris & Co, designed by Burne-Jones, for various churches in Birmingham; the Museum was enriched by the huge watercolour The Star of Bethlehem, brought in in September 1891 after being exhibited in London.

The Star of Bethlehem, Burne-Jones's "huge" work for the gallery (featured on p. 78 of the catalogue).

A few years later, round the turn of the century, "the leading artists of the Birmingham group succeeded in forging a distinctive style" which was directly inspired by the aesthetics of the second Pre-Raphaelite generation: Maxwell Armfield, Arthur Gaskin, Kate Bunce, and Joseph Southall, among others, who fully deserve this opportunity for revaluation. In many ways, then, Radical Victorians usefully complements the exhibition it now accompanies, as well as being thoroughly informative in its own right.

Links to Related Material

- Review of the Radical Victorians exhibition itself, 10 February - 31 October 2024

- The First Pre-Raphaelite Group Exhibition

- [A Review of] Pre-Raphaelite Treasures: Drawings and Watercolours from the Ashmolean Museum at the Watts Gallery, Compton, 8 March-12 June 2022

- [A Review of] "Pre-Raphaelite Sisters" at the National Portrait Gallery, London, 17 October 2019–26 January 2020

Bibliography

Ellis, Martin, Victoria Osborne and Tim Barringer. Victorian Radicals, from the Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement. Munich, London, New York: American Federation of Arts, Del Monico Books/Prestel, 2018. 288 pp. Paperback ed. from the Museum Shop, £39.99. ISBN 9781885444479

Created 21 July 2024